Retrospective: Turbo Esprit

Where the streets have no aim.

You know that time has marched on when something that everybody did without really thinking finds itself categorised and pinned down by a catchy title. Take "emergent gameplay", for example.

Today, that's the fancy game theory term for players mucking about and making up their own rules, regardless of what the designer intended. In the eighties, that was just how we rolled, yo.

Maybe it was because so many of us were playing from hooky C60 tapes copied off a mate, or maybe it was because we just couldn't be arsed to read the two paragraphs of instruction on the inlay, but I'm convinced that most gamers of 20-odd years ago often had only the vaguest idea of what the goal of their favourite games were.

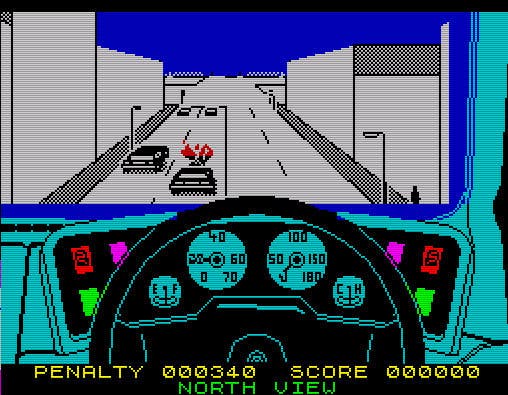

That was certainly the case for Turbo Esprit, Durell Software's hugely ambitious free-roaming car chase for the ZX Spectrum. It's a game with which I spent many happy hours without ever really knowing or caring what I was supposed to be doing.

Turbo Esprit still impresses in 2011. This is a 3D driving game set across four fully mapped cities, each packed with naturalistic details such as pedestrian crossings, roadworks, one-way streets and persistent traffic that actually follows the Highway Code and doesn't simply vanish once it's off screen.

All this is squeezed into 48k, a smaller file than you'd need for a JPG of the game's cover art. It's simple and rudimentary by today's standards, of course, but favourable comparisons to Driver and Grand Theft Auto, Esprit's genetic descendants, are as obvious as they are deserved.

Having picked a city from the four on offer (Wellington, Gamesborough, Minster and, er, Romford) you're free to roar around the wireframe streets at will. Roar, of course, being a relative term. As forward-looking as the game was, sound design is not an area where it excels.

The theme tune is a classic, a jaunty whistle-along number that has lodged in my brain for 25 years, but in-game the mighty Lotus was reduced by the Speccy's farting sound chip to little more than a series of clicks and quacks, like a duck being beaten to death with a Geiger counter.

None of that mattered. Nor did it matter that there wasn't really anywhere to drive to. You could go wherever you wanted, travel the wrong way down one-way streets, knock stick men off ladders and shoot your way out of dead ends by turning your machine gun on the queue of constantly spawning civilian cars blocking you in.

You took penalty points for civilian slaughter, but since hardly anybody knew or cared what the points were for, that didn't matter either. It was a pure a sandbox as it's possible to imagine.

Control-wise there were some clever ideas. As well as shooting your gun, the fire button doubled as a handbrake. When it was pressed in conjunction with left or right your sleek sports car would hurl itself in the required direction.

Do this at the correct moment as you thundered through a junction and you'd instantly slip onto the new road without losing momentum. Get it wrong - as you invariably would - and you'd end up lodged horizontally across the street and forced to perform a laborious three-point-turn or, worse, you'd die instantly in a squelchy red fireball.

Turbo Esprit was produced with "technical assistance" from Lotus, though this was clearly a far cry from the exacting demands of todays relationship betwixt videogames and sports car manufacturers. The famous eighties vehicular icon looks more like a bar of soap on wheels and explodes at the slightest provocation, presumably not the thrilling endorsement the company was hoping for.

Even so, in an era when I considered Street Hawk to be the pinnacle of televised entertainment, Esprit's mix of navigational freedom and Russian roulette cornering was more than enough to scratch my gaming itch.