Behind Sable's many masks: identity and storytelling in a sci-fi desert

Sands good to me.

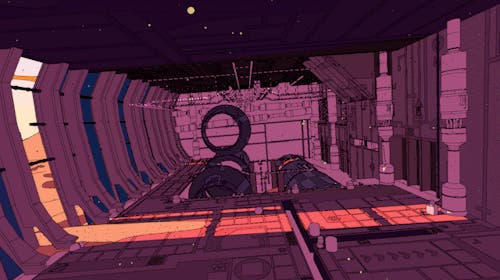

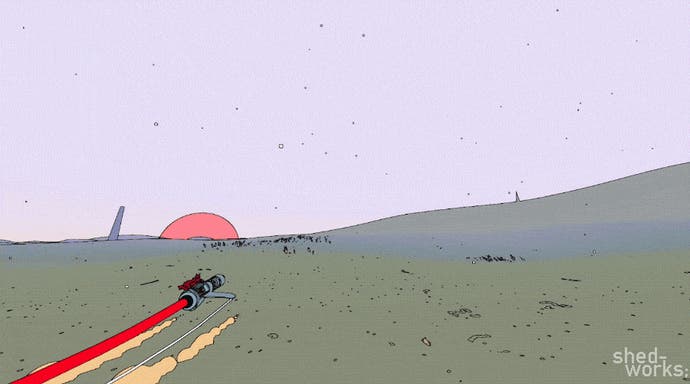

When Sable first appeared at E3 last year, it was enough to snap me out of my early-morning slump, sit up straight, and message my friends in excitement. The game's stunning visual design, dreamy environments and haunting soundtrack were so abruptly different from anything else at the show. It was enough to instantly push Sable to the top of my most-anticipated games list: a feeling shared by others, as I would later find out.

In the months since E3, Sable has received a huge amount of attention - not only from journalists, but from fans admiring the game on social media. Unsurprisingly, most of the discussion has focused on the art style and the game's influences, with names such as Moebius, Ghibli, Star Wars and Breath of the Wild frequently cropping up in discussions.

While it's both unsurprising and entirely justified for so much focus to be given to the art style, I wanted to dig a little deeper into the ideas driving the story, and the main character herself - Sable. What is she searching for? What sort of world does she live in? Why is she wearing a goat skull on her head?

To find out, I went on my own little voyage: to a shed in North London, where Sable is being made.

"I think the project has become more public, more publicly known, bigger than we ever would have anticipated," Gregorios Kythreotis, Sable's art designer and one half of Shedworks, begins the conversation by saying.

We're in a small but modern garden shed, with an electric radiator to keep away the January cold, and just enough room for three people - and a huge stack of art books. If you hadn't twigged yet, this is where Shedworks - Sable's indie developer - gets its name.

"There was a clue, if you look back, when we took it to the pub on London Indies night. We had taken stuff to the pub before but nobody was really that interested. Whereas with Sable... we put a laptop there, and we just left it open with a controller. We had people gathering around it and someone recorded video of it."

Sable, of course, has come a long way since its first blocky demo. It's due to release on PC and Xbox later this year - and having sorted fundamentals like terrain generation, Kythreotis and Daniel Fineberg (Sable's programmer) are now focusing on content. Things like the story: something which will likely make or break Sable due to the explorative nature of the game.

"That's something we do need to be careful of," Fineberg says on the topic of Sable's streamlined game mechanics. "Without an incentive to explore it's like walking around a big museum - everything's standing still, and you're just looking at it and appreciating it but you're not really interacting with it."

"That's where the writing, the environmental design, the level design, all of that will come in," Kythreotis adds. "But we also wanted to make a game that wasn't stressful. Or the tension doesn't come from the mechanics itself but rather a story theme: it's not about having faster reactions than someone else, you just care about this character and the things that happen."

And the story certainly sounds fascinating.

Rather than follow the typical hero's journey narrative we've seen so often, Sable is taking an unusual approach to storytelling. Sable's writer, Meg Jayanth, received critical acclaim for her writing for 80 Days: a mobile game with a complex branching narrative. Shedworks is hoping to introduce a similar freeform narrative to Sable.

"The beauty of 80 Days [is] you don't see all of the content - you can't - and it's very unlikely two players will have the same story," Fineberg says. He goes on to explain that this narrative style means Sable can escape some of the pitfalls of open world games - which Fineberg rarely finishes "as they just dump so much content on you".

"You start [Sable] with your family and you then leave home. The ending is just 'she decides to go home' and you send her home, and just kind of end it. You maybe didn't see everything there is to see, you maybe didn't see all of the world, but you saw what you were interested in and hopefully that's a cool story for you."

The reason for Sable's (the protagonist's) voyage across sand dunes and between communities, Fineberg explains, is because she's looking for a mask. In Sable's world, everyone hides their face with a mask - an item which also symbolises their role or job. Even children wear masks, but these are fairly meaningless until the youth reaches adolescence. As part of a coming-of-age ceremony, Sable tries on many, until she settles on the one that best represents her.

Sounds like my efforts to buy a prom dress - but more serious, and hopefully more successful.

Intrigued, I asked whether the masks allow players to interpret Sable's character based on their experiences in the game.

"It's like a form of player expression," Kythreotis agrees, before hastily adding: "she is a character though, and that's important to know and stress. We will be informing the player of her opinion on things throughout the game."

To illustrate the point, Fineberg compares Sable's character to Link from Breath of the Wild - a game which has heavily influenced the pair's work.

"Link is a shell, he doesn't speak, he doesn't really have a personality aside from a desperate need to save the world, and that's quite a common thing in open-world games. The character is a blank slate so you feel like you can do whatever you want."

(The pair do still love Breath of the Wild, despite the harsh words on poor Link. I spotted at least four Zelda art books in the shed.)

"She speaks, she has thoughts and feelings about things, but they're not necessarily the same as yours, and that's really important," Fineberg continues. "We don't want it to be a 'player-chooses-their-own-character' type of thing, we wanted her to be an actual person."

The mask discussion led me to another topic - Sable's character design. If the children's masks don't mean anything, why choose a goat mask for Sable?

"Part of it is the word Sable - we had that word already, and there's a Sable antelope," Kythreotis adds with a laugh. "It tied into the theme of climbing as well, as goats climb things, and I wanted something that's silhouetted and felt iconic, and that was the focus of that design, because it's a mask you can change.

But I wanted to create something that felt like the equivalent of Link's tunic for Sable, and so that was where that focus came from."

Another interesting aspect of Sable's character design, for me, was her androgynous clothing - something helped in part by her covered face, as Fineberg explains.

"If everyone in that world wears masks then that changes their relationship with identity, and they choose which mask they wear. Your mask is your identity more than your body, and if you don't show people your face - that's more important to them, it changes the way they think about your identity, which is not so much tied to your biology as to the way you represent yourself to the world."

I myself admit when I first saw Sable appear, I had no idea what gender she was: a reaction Kythreotis says he enjoys.

"I think it was important that we didn't take an archetypal, typical feminine approach to the character design. Or overtly, at least. It was an approach that was as gender neutral as possible, and we want the player to make decisions about how they approach different situations without applying gender roles from our world."

"It's much more interesting than having our standard, gender role-patriarchal society projected into this sci-fi universe. We're not necessarily going out there saying this game is about a utopia or a dystopia, or anything like that, it's just a different place.

Something that often worries me about explorative games is that the visuals come at the cost of gameplay, and if done poorly, feel rather empty. The curse of the walking simulator, as it's been termed.

With Kythreotis and Fineberg, however, I came away from the shed with high hopes for Sable. Every design point we discussed - from the themes, music and story to the gameplay - seems to have been carefully thought through, and the team are aware of the potential dangers of the genre. More than anything, I can't wait to decide on a mask for Sable.