Why Unreal deserves to be remembered alongside Half-Life

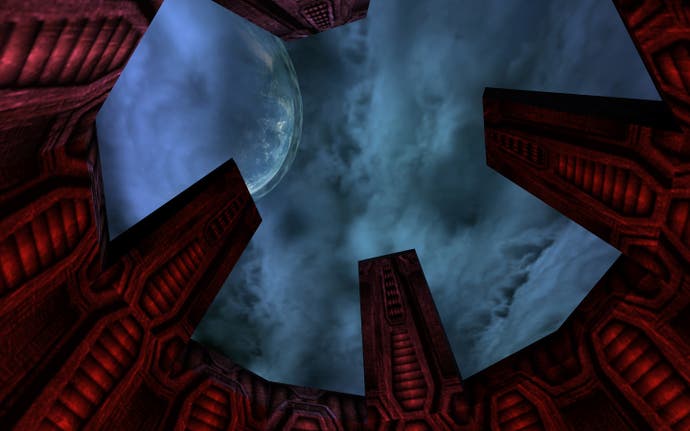

Skaarj tissue.

The anticipation is the best part. Clutching a game box, and trying not to get carsick as you flicked through the manual on the car ride home. For someone used to the cardboard characters of the Saturn, N64 and Playstation, Unreal wasn't just a graphical upgrade: it was a revelation, a game that looked impossibly beautiful even without a graphics card. Even today, with a judiciously installed HD texture pack, it's still a sight to behold.

You may know of Unreal from the Unreal Engine, which has fuelled a surprisingly diverse set of games over the years. But before there was the Unreal Engine, there was simply Unreal, a humble first-person shooter released in 1998. You are Prisoner 849, incarcerated on the space vessel Vortex Rikers when it crash-lands on the planet Na Pali. You emerge from your cell, the only prisoner left alive in a strange and hostile world. Your objective isn't to defeat the forces of hell, the Nazis or any other antagonistic bogeymen. Your only goal is survival.

16 years after Unreal's release, Prisoner 849's exit from the Rikers and into the wilderness of Na Pali is no less impressive: that juxtaposition of the ship's metallic carcass teetering on the edge of a waterfall evokes the feeling of a spoiled paradise, a world corrupted. As you explore this strange place - haunted mines, temples, monasteries and increasingly convoluted alien installations - you start to question who the real alien is around here.

Na Pali is the home planet of the Nali, a placid and spiritual race of space farmers, who are being subjugated by the brutal Skaarj (it's pronounced 'scar', but the game never actually tells you that), who are basically the Predator's lizard cousins. The Skaarj aren't a traditional shooter nemesis in the vein of the Strogg, Combine or Helghast: they're inarguably evil, but you're not actually there to thwart that evil. Rather than being a heroic space marine sent to save the Nali, the player is a mere intruder, an interloper. The Nali diaries you find often mention a messiah coming down from the heavens to rescue them, but that's not you. The Skaarj are really just another obstacle in the way of your escape.

What makes Unreal unique is that it's not just a game filled with interesting aliens: the game itself is alien, a world apart from other shooters of the time - and even shooters today. It meddles with the traditions of the genre through an aesthetic that is part science-fiction with the Skaarj and their biomechanical technology, and part high fantasy with the mystical Nali and their thatched cottages.

The weapons are unconventional, taking in a bog-standard laser blaster that is eventually upgraded into an electric death cannon, a gun that launches nuggets of hot metal and a giant blade that shoots smaller razor blades that ricochet off the walls. There is a refreshing lack of conventional shotguns, assault rifles and rocket launchers - Unreal's rocket launcher can fire a volley of six at a time, but somehow it is called the Eightball. One gun shoots explosive sticky green goo, and it can lay claim to being one of the first weapons to feature alternate firing methods and combo attacks: launching a ball of energy from the ASMD and then detonating it with the beam fire is the first-person shooter equivalent of chaining a fireball into a dragon punch.

Unreal's artificial intelligence is equally alien: some creatures like the Slith and Kraal are as dumb as it gets and will greedily eat whatever you fire at them, but the Skaarj are ferocious and fiendish, just as capable as any deathmatch bot. They dodge your bullets before you've fired them, a cheap if endearing move. When you combine a set of guns packed with strategic possibilities and fierce AI that can still provide serious opposition, it's easy to see how the Unreal Tournament series became so popular, even with people who didn't have internet access.

But in spite of the excellent multiplayer potential, Unreal's single-player story is not just a straight shooting gallery. Instead, it is as much a game about exploration as it is about shooting aliens in the face. For every thrilling firefight, there's a boat ride to savour or a moment of fleeting tranquillity. The Unreal Engine was perfectly suited to building expansive environments and creating real worlds, rather than the dull, interconnected brown boxes of Quake.

One such place, the Sunspire, is a plinth of rock turned into a Nali refuge, surrounded by a moat of lava. It practically pierces the skybox and hurts your mouse hand to crane your avatar's neck up at its summit, and you can ascend the whole thing without ever seeing a loading screen, pausing at the top to catch your breath and watch the light reflected off Na Pali's twin moons. At one point, you approach another crash-landed Terran mining vessel called the ISV-Kran, a ship so overwhelming you feel like an ant crawling towards the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rather than just game spaces, these feel like real places.

And real places can tell real stories: before you find your first gun in Unreal, you collect the Universal Translator, an essential tool for deciphering the stories of the Nali. They've carved their lore into the walls of their temples, and you take on the role of a spacefaring Indiana Jones as you explore the architecture and solve its riddles. The human corpses you find scattered across Na Pali have their own stories to tell, too: at the monastery of Bluff Eversmoking, you find a tale of daring resistance against the Skaarj oppressors from Kira Argemenov, the ISV-Kran's science officer. Although we often think of Half-Life as the original shooter with a worthwhile story, Unreal got there first - and is arguably the more compelling of the two.

Ultimately, Unreal's story is not one of stopping the Skaarj menace and playing the hero. It is a melancholic tale in a world we are powerless to save: every human we meet is already dead, and every Nali we meet is never far away from danger. We're only ever saving our own skin, destroying an alien base and then fleeing the crime scene in search of another way off this wretched paradise. Tonally, it's much closer to Fallout 3 or Dark Souls than the "M-M-M-MONSTER KILL" hijinks of Unreal Tournament. Sometimes, as we wander around a deserted cargo bay waiting to be ambushed by an enemy hiding in the dark, it is more reminiscent of a survival-horror game than a shooter. And that's fitting because you're only just surviving Unreal, never conquering or mastering it.

Unreal, as the name suggests, remains somewhat enigmatic and otherworldly. Overshadowed by spin-offs, the fruits of its engine and Valve's genre-defining Half-Life, it never quite got the recognition it deserved. I think that's part of why I like it so much: you play as someone who doesn't belong, in a game that doesn't seem to belong either. But it's so much more interesting to play as the underdog, to feel outnumbered and alone and come out fighting. We can return to Na Pali any time we want, but Unreal will always be alien to us.

Alan Williamson's book 'Escape to Na Pali: A Journey to the Unreal', co-written with Kaitlin Tremblay, will be on sale on 23rd June through Five out of Ten.