Verses Mode: What can poetry do for video games?

We speak to the editors of two new books about what's to be gained from the meeting of two artforms.

Who is your favourite version of Lara Croft right now? The cartoon star of Temple of Osiris, with her bubblegum-blue leotard, or the 2013 reboot's bedraggled gap year student? For me it's neither. I'm much more taken with the Lara Croft of Melissa Lee-Houghton's "Hot Pursuit", which introduces the final section of video game poetry anthology Coin Opera 2: Fulminaire's Revenge. Largely, that's because this incarnation of Lara won't do what she's told. Lee-Houghton portrays the character as neither an instrument of the player's will nor a swashbuckling heroine, but a kind of wayward protégé who must be laboriously won round if any progress is to be made.

Setbacks are represented as the result not of pushing the wrong button or fudging the timing, but of Lara's refusal to play along - "my hands react to your rage / like my body reacts to hot water". The tone shifts violently, line to line, from admiring ("you don't thirst / I love that about you") to resentful ("you want to go it alone"). Even Lara's mortality comes to be viewed as a kind of misbehaviour, a cheating of Lee-Houghton's expectations for the character. The poet pictures Lara's corpse being fed to wolf cubs, her pony tail hacked off, only to recall with a start that the point of her death is also the point at which the illusion collapses, rolling back to the previous save: "you were never there".

Where the latest reboot has papered over such scrapes and blemishes, Lee-Houghton's piece rediscovers the invigorating frustrations of classic Tomb Raider - of fighting Lara's wheelbarrow-esque turning circle and her pickiness about handholds, smartly couched in lines that sometimes flow together into sentences and sometimes fall apart, like badly calculated jumps. In the process Lee-Houghton also tells us things about herself, or at least the self she chooses to be for the poem's scope, comparing the failings of her flesh to Lara's "freak show" physique:

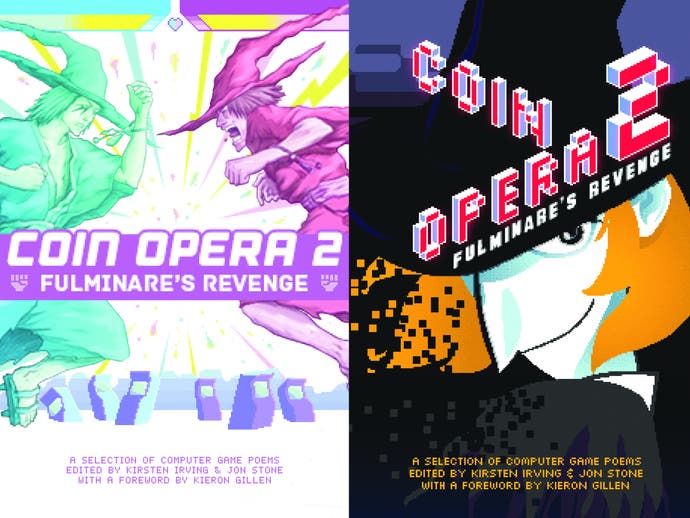

Coin Opera 2 aims to celebrate such interactions, declaring boldly on its cover flap that "games and poetry have a lot to say to each other". Edited by Jon Stone and Kirsten Irving of London-based Sidekick Books, the collection is an attempt "to combat two prejudices simultaneously: the prejudice against computer games that denies the artistry of their content, and the prejudice against contemporary poetry that rejects its readability and relevance".

This not-inconsiderable endeavour begins with the cover, which evokes the hyperactive tackiness of fighting game box art: pixel wizards lunge at one another across a glaring expanse studded with arcade cabinets. The collection ransacks the lexicon of video game design for structuring principles, to dizzying effect. Mid-way through his editor's intro, Stone is kidnapped by a gremlin and carried away to the epilogue, leaving the reader to quest through three Stages - "Dust-Up Forest", "Pluck & Plunder Island" and "Brainthunder Mountain" - comprising 20-odd poems each, "defeat" whopping Boss poems and spectate on "multiplayer" matches between contributors. There are cheeky typographical experiments based on Snake and Peggle - a welcome change of pace after a gruelling tussle with a cento or sonnet sequence, like stumbling on a bonfire in Dark Souls. There are collaborative poems that are modelled on the logistics of strategy games. There's even a piece that consists of Dualshock controller icons.

If you're a fan of poetry, talk of Snake and logistics and Special Moves may leave you gasping for air. If you're a dyed-in-the-wool gamer, the mention of centos and sonnets and typography may be similarly bewildering. Coin Opera 2 derives much of its force, say its creators, from the sheer enigma each medium sometimes represents to the other. "Sometimes the mystery works for you, something for the reader to figure out, whether it's a quote from the manual or a character. It takes on a life of its own outside the game," observes Irving, when I meet her and Stone for coffee.

Nonetheless, Stone interjects, one of Coin Opera's founding convictions is that video games are now familiar and accepted, that their trappings and terminologies can be drawn upon by writers as confidently as the once-arcane language of cinema. "As a medium, gaming has been around long enough now to have its own culture, and language and world and internal logic that's accepted but is really hard to explain to people who are outside it. It's a rich metaphorical landscape for poems - once you have an established set of worlds, and established tropes, it becomes fodder for talking about the human condition, finding ways to express yourself or start conversations."

A specific inspiration for the experiments at Sidekick Books was the work of Ross Sutherland, whose Street Fighter 2 sonnets are born of what Stone describes as a wish to treat video games as a mythology - "a series of symbols that can be reconfigured", available for deployment in poems in much the same way as the events of the Iliad and Odyssey. Sutherland's "Ryu" approaches this with a well-tempered sense of its possible absurdity: the poem turns the unleashing of that iconic "cannonball of chi" into a dictum from The Art of War, playing upon "code" as button sequence and as warrior's creed. The piece's capacity for affect is a question in part of the attack's ubiquity - "hadouken" is one of gaming's gateway drugs, a trick many will recognise even if they've never played Street Fighter - but Sutherland throws in a few rueful tactical tips for newcomers.

Andrew Donovan's "Holy Shit (Applied Reverb") leans on the concept of a mythology more explicitly. It's among the poems published by Cartridge Lit, a wonderful online magazine founded in 2014 by Joel Hans and Justin L. Daugherty to showcase the best game-inspired poetry, fiction and non-fiction. The poem certainly supports Daugherty's interest in "work that emerges from and outside of games, to transform the subject material and address specific, important issues" such as the spectre of imperial violence. Among other things, it turns a spotlight on the military-industrial complex that shapes both video games and the communities that feed on them, styling StarCraft 2 a "garden of unthinkable currency".

What I like best about Donovan's piece, though, is its humour. The poem seizes on one of the more farcical bits from the Iliad, in which the Greek hero Diomedes goes on a highly unlikely rampage through the Trojan ranks. Donovan recreates this as a stream of kill notifications. Elsewhere on Cartridge Lit, Matthew Burnside turns in a wonderfully silly lampoon of Williams Carlos Williams' famous imagist poem "This Is Just To Say", with the stolen plums swapped for the unleashing of a red shell in Mario Kart. "Forgive me," it phlegmatically concludes. "You were winning / and I was not".

If humour is one way to assuage doubts about the compatibility of games and poetry, direct formal inspiration or overlap gives rise to the most intriguing pieces. Poets who merely write 'about' games run the risk of muddying the constraints and devices that distinguish the medium, much as catch-all references to 'poetic language' hide the techniques and patterns that separate poetry from flowery prose. Some of Coin Opera 2's finest pieces latch upon the inner workings of video games as a basis for new ways to assemble language. Irving and Abigail Parry's collaborative Versus Poems, for instance, renders an exchange of blows as an exchange of couplets: the first line of each couplet transforms all verbs from the last line of the previous into nouns, thus simulating the blocking of an attack.

The Versus Poems aren't 'about' games at all - they're written from the perspective of famous literary personalities, pitting Dolores Haze from Nabokov's Lolita against Sredni Vashtar from Hector Hugh Monro's story of the same name. But they capitalise upon how games actually work in ways that transcend the limitations of subject matter, and add to the technical repertoire of poetry. "It felt more spontaneous as a poem," Irving observes of a related "multiplayer" experiment. "I know a lot of people have been schooled to edit the crap out of poems, and that can be brilliant, that can really pan out, or it can feel like it's been workshopped 17 times."

This seems a fruitful line of thinking, given the readiness with which lay commentators brush many games off on the strength of their characters or plot - the cleverness of Call of Duty's design is easy to miss, if you confine your attention to all the shouty men with shaven heads. Speaking of shooters, Stone's nine-part "Headstone Fortress" tries its hand at something similar. The sequence evokes how classes in Team Fortress 2 allow for variation, originality within the same to and fro of combat, by adopting roughly the same phrase structures for each part while changing up the words that comprise them. Part of the fun is working out which Team Fortress personality has lived and died in each instance.

Aside from celebrating not just who or what games involve but how they function, poetry's influence might also correct the industry's long-standing bias towards young men. Irving comments that "there are a lot more women working within the artform of poetry to start with, and they can queer a few narratives, monkey around a bit, look at minor characters, look at different angles." It's a point captured by her prose poem "Ten Green Bottles", which shows what completing a level in Lemmings might be like for the lemmings. Among the piece's most affecting tactics is simply to give each lemming a first name and gendered pronouns. "A lot of the [female poets] we spoke to gravitated towards puzzle games, things you can repeat in your spare time," Irving notes. "I think for some women there is still a fear of failure in games. You're less likely to go out on the ledge, so to speak."

There's plenty of fear of failure in "Hot Pursuit". There's also a feverish inconclusiveness - the poem ends with Lee-Houghton exhorting Lara to "inch towards me", as though coaxing out a scared child. The salient point here is perhaps that both games and poems reject resolution: if poetry can be defined as language freed from the need to directly and unequivocally "mean" anything, video games are also, by definition, incomplete and without obvious consequence, arising as they do from the friction between player and artefact or avatar.

Cartridge Lit's Joel Hans argues that too many developers try to hide from this, preferring to ape techniques from Hollywood in hopes of gleaning a little reflected glory. "It needs to consist of so many acts, each of which put the player into a certain emotional state, thanks to the deliberate placement of this or that swelling orchestral track, and so on. Every movement is designed with a specific destination in mind." A poem like Lee-Houghton's "Hot Pursuit" reminds us that the most enticing games are often those that confront us with something or somebody alien, and leave us to make sense of the interaction. "Poetry is often a conversation between different people at a distance," observes Jon Stone. "Somebody is inspired by somebody else, who is inspired by somebody else. Movements inspire counter-movements. And games are about conversations as well."