Viewfinder's built around a single moment, and it's great

Snap!

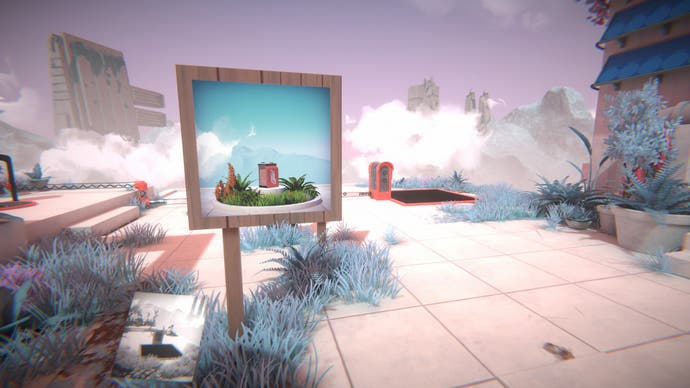

Viewfinder is a puzzle game built around a single moment that I will simply never tire of. Here's how it works. You see a bridge. You lift your camera and take a picture of the bridge. You take the picture you now have in your hand - the bridge - and then hold it up elsewhere in the world, maybe where there's a gap in the ground between you and the spot you want to get to. Choose the location, the angle, and commit. Voila! The picture of the bridge is now an actual bridge that you can walk across. Gap? What gap.

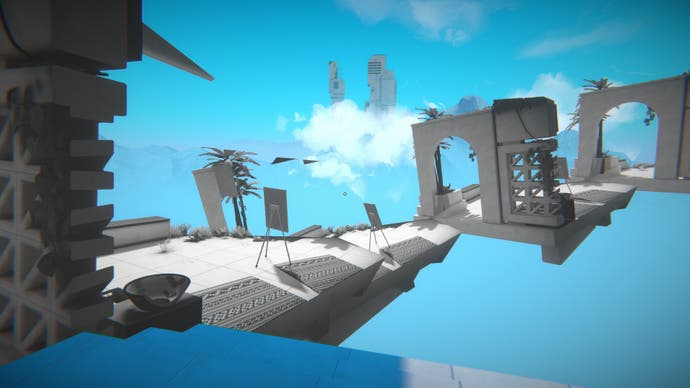

This is magical. And it's magical I think because it brings together 2D and 3D worlds and encourages you to mess around with their inherent conflicts. You take a 2D picture of a 3D object, but you can then transport that 2D picture somewhere else and turn it back into a 3D object. There's also something really lovely about walking out into the picture - something Lewis Carroll would have built a book around. Your 2D/3D imprint on the world is never entirely neat. You will have eaten into the existing 3D surroundings, sometimes catastrophically. You will have sliced up the ground. You will have imprinted a new grayscale horizon across part of the Technicolor sky.

I love all this. Viewfinder loves all this. And it uses this idea to power a bunch of complex yet compact puzzle levels that you wander through, one epiphany at a time. There's a wider narrative, but it didn't grab me to be honest. Maybe it will grab you! For me, I was too busy chasing the next moment where I hold up a picture and change everything.

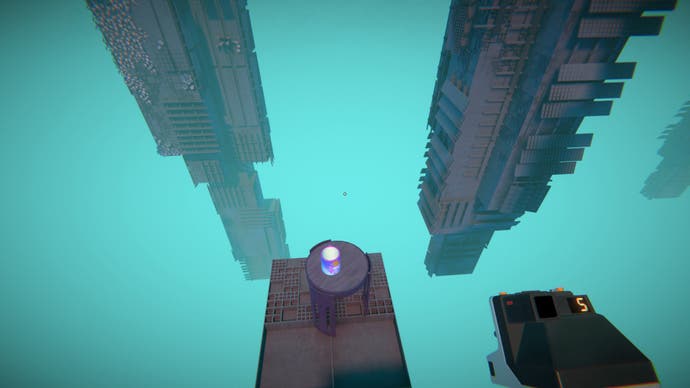

The puzzles are always pleasingly direct. You'll drop into a 3D environment - walkways, rooms, the odd staircase - and you'll need to reach the transporter that will lead you to the next puzzle. Get to the exit. That's it. Sometimes the transporter needs to be powered, which means you'll need to locate batteries down and lug them around. Sometimes the transporter needs to be reached, which means you'll need a way to cross gaps. Sometimes the transporter will be upside down or stuck to an inconvenient wall which means you'll need to work out how to get it back on the ground. Sometimes the transporter will be caged by some kind of violet material that does not show up in photographs. Sometimes it will be actually made of that material! Onwards. Outwards. You get the idea.

All of these problems can be solved by taking pictures, rotating them, lining them up in improbably perfect ways. A wall can become a floor if you rotate it. A floor can become a ramp. Some levels give you loads of leeway - loads of photos to take. Others give you just a few. Some give you none at all and you must locate pictures in the world to use. These can bring about jarring art style shifts: pencil lines, pixelart. Then there are photocopiers which allow you to create fuzzy duplicates. Onwards. Outwards. You get the idea.

I get the sense at times that Viewfinder's creators stumbled on this perfect moment - the moment you step into the photograph - and then worried it wasn't enough. Hence the levels that don't let you have a camera, or the levels that put obstacles between you and your goal that do not turn up in photos. All of these things are clever and lead to elegant solutions - my favourite of these should not be spoiled, but relies upon using fixed cameras that are placed around certain levels - but the thing that's truly great about Viewfinder requires a viewfinder you can actually carry around, I think.

This is because cameras are a perfectly imperfect kind of magic. Whenever you look into the viewfinder, what you find in there is a world that's been gently altered by this new way of seeing it. And when you get your photos back in the post or develop them yourself, you'll see that the world you saw through the viewfinder has changed yet again. Reality, the view down the lens, what you see rendered as a photo: they're all just different enough to be pleasantly weird. This is the sensation the best levels of Viewfinder really taps into. It's why it would be a fascinating game even if the puzzles weren't as good as they are, or as obligingly compact and non-knackering to solve.

There's something else I love about the game. Last thing. Its environments are scattered with clutter - cups and plants and Rubix Cubes and whatnot. But they're also filled with chairs. And when you reach a chair you get a prompt: sit. There's no immediate use to a lot of these chairs. You don't sit and suddenly find yourself facing the solution. But they are the fruits of an understanding on the developer's part, I think. Sometimes you need to sit down and see things from a different perspective in order to proceed. Sometimes, as any photographer will tell you, you need to put the camera aside and just look at the world as it is.