Viewtiful Joe retrospective

Some like it REEEED HOT!

This is the story of how an artist adapts and refines his craft. It starts with a challenge. In a recent interview with Nintendo president Satoru Iwata, The Wonderful 101's director Hideki Kamiya talked about his first wholly original project. "I began developing [Viewtiful Joe] when my boss at Capcom, Shinji Mikami-san, said, 'Try doing the design process by yourself.'" A Capcom star on the rise, Kamiya had previously directed Resident Evil 2 and Devil May Cry - but Viewtiful Joe was to be the first title he'd design from the ground up.

Viewtiful Joe might seem the kind of classic that needs no introduction, and then you think about the fact that a master of the 3D genre should have chosen to design a 2D action game as his debut title on the then-next generation of hardware. But Viewtiful Joe is no normal take on two dimensions, and this surely has its roots in the timing of Kamiya's rise to prominence.

Kamiya's big break had come in directing Resident Evil 2 (he was a planner on the original.) The Resident Evil series was one of the most successful games in that early 3D era of home consoles in the late 90s, when the original PlayStation was the only real game in town. And this trained a generation of Capcom's finest minds in what is now a niche art - 3D worlds built to be viewed from fixed camera angles. Kamiya didn't just design Resident Evil 2 in this style, of course, but would afterwards design Devil May Cry, probably the first truly great 3D combat game and one that used a fixed camera.

Viewtiful Joe is a game in love with the camera, that much is clear, but in a more strictly physical sense than usual. A videogame camera, whether you're playing in 2D or 3D, is nearly always a floating fixed point. There are many exceptions to this of course, and many cul-de-sacs too - one of which is this 'Resi camera.' You can see the greatest advantage of a fixed camera instantly: control. You know what the player's viewpoint on a scene will be at all times, an effect that the first Resi used superbly in its player-facing corridors. Peeking around corners would have ruined that game.

Think about how pervasive that style was for years, before being utterly superseded. This is an inevitable result of an industry that intersects art and technology - and what led to the Viewtiful viewpoint. Viewtiful Joe is a game about a camera fixed on one plane, observing a world that is suggestive of many more. When Joe jumps the camera doesn't jump with him, but jerks its gaze upwards like an audience member. When Joe turns corners the camera stays fixed on him, but the environment itself rotates into view. It is a radical visual style, even now, one that puts the game's audience in the position of observer as much as participant.

Which is, of course, the point. Viewtiful Joe takes place in movieland, after Joe's girlfriend Sylvia has been snatched from their local cinema by an on-screen monster - and Joe gets pulled in right after. The story's enjoyable hokum but the setting is far more; this is a game that is built mechanically and visually around its cinematic metaphor, a production about putting the player in charge of a production. This is why Kamiya is a special designer; Viewtiful Joe isn't a game about being stylish. The style is the game.

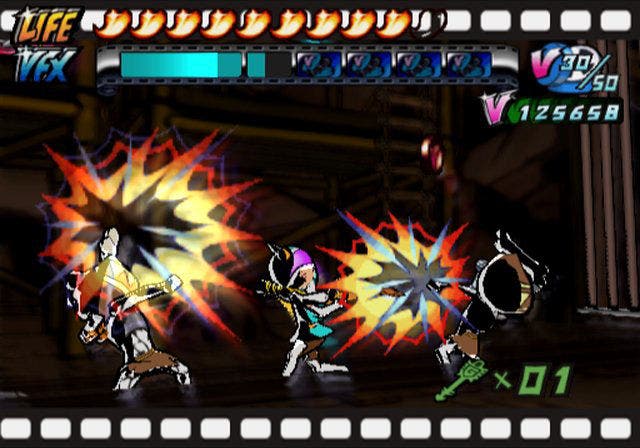

Who needs boring old SFX when you have VFX? Joe can make everything move in Slow motion to deal double damage, dodge bullets, and send enemies crashing into one another. You can hit Mach speed to punch so fast Joe bursts into flames, his after-impressions bouncing around the screen like the devil's own echo. And hell, let's finish it off with a big sexy Zoom - the camera comes right in as our man strikes a pose, stunning nearby enemies and unlocking Joe's most stunning moves.

At times Viewtiful Joe is the most amazing game ever made - though to be fair, you could say this about most of Kamiya's stuff. And these powers always come at a price. Viewtiful Joe's unforgiving nature is simultaneously its greatest strength and weakness. There is a sequence near the end called The Magnificent 5, which presents you with a boss gauntlet, and it is scalp-rendingly difficult. I will defend the boss gauntlets in any other Kamiya game, but not this one, because the bosses are the big flaw in Viewtiful Joe's design - though explaining why illuminates the brilliance of the remainder.

You have to consider them in the context of Viewtiful Joe's combat system. The best technique against bosses in the game, absolutely without exception, is dodging their attacks then unleashing a combination of Slow plus Zoom plus a good-old Red-Hot One-Hundred. The bosses all have their own attack patterns and timings to learn, for sure, but everything comes down to that one tactic - which makes these fights not just brutally hard, but actually quite boring once mastered. Think about it this way: you're always reacting to their movesets, rather than exploiting Joe's.

Against normal enemies things are different. Viewtiful Joe's system is built around multipliers which are triggered by knocking enemies into one another - so while you might only get 10 or 20 V points per hit, if you manage to use that hit to knock one enemy into the three behind it you'll also pick up a three times multiplier. Keep that sequence going, by knocking more enemies into more enemies, and soon your basic combat score will be multiplied to gigantic levels after every fight. It's such a simple idea, but the way it encourages you to play ensures the player ekes out every last quirk of Joe's moveset to both keep that combo going and keep enemies knocking into one another. It gives you a goal, in other words, beyond simply defeating X opponents, and that goal is dependent on creative free-flowing play.

At its best, and Viewtiful Joe is frequently at its best, this is a game that gives you freedom of expression with four limbs and a head-mounted Voomerang. But even then, I always saw Joe as something more than the stylish pugilist he's remembered as. It's to do with that camera, and perhaps the kind of thing that only becomes obvious with hindsight, but Viewtiful Joe is gaming's most devastating love-letter to cinema. Or to be more precise, cinematic techniques. The kind of thing that only a director like Hideki Kamiya, schooled in a dying visual style and searching for a new direction, could have imagined. The kicker? The industry's mainstream prefers the more literal copies of an antecedent that was always going to inform gaming's future path - but should never have been allowed to dictate it.

For as long as there is a videogame console capable of playing it, at least, there will be Viewtiful Joe - mach speed, slowmo and zoomed choreography, all in the hands of us first-time directors that can learn to control our own action movie. Capcom and their golden generation cracked the cinematic inheritance; how depressingly predictable that, even now, no-one quite realises.

During the game's opening level, the big screen's Captain Blue tells Joe to activate his latent powers with the musty and mystic word "Henshin." Sure he could, but Joe isn't some actor being rolled out to spout the same old lines for a soporific crowd. He's at the forefront of interactive entertainment, and he's mine and yours and Kamiya's avatar. Joe strikes a pose, raises a fist, and puts a red-hot spin on things: "Henshin a-go-go, BABY!" Viewtiful.