Volume review

Loud quiet loud.

One of the most refreshing things about Volume, Mike Bithell's second game after the charming Thomas Was Alone, is that the design is entirely naked. This isn't a game that tries to hide its systems behind a fig leaf of "immersion". It's not a game that wants to grease your path to victory so you can see the ending.

It is, proudly and defiantly, a game. Games have rules, and Volume's are spelled out in unmissable ways. Like the great pioneering arcade titles, everything you need to play the game is right there on the screen, in the sound effects, in the colour schemes and animation. That's design, and Volume isn't afraid to let it show.

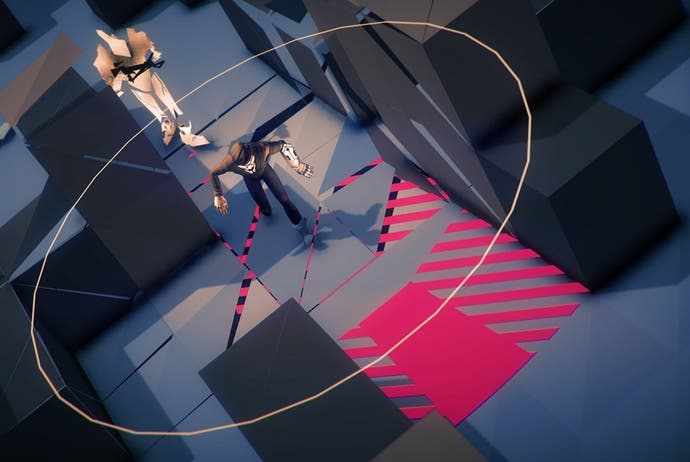

At a surface level, Volume seems like a quantum leap from Thomas Was Alone. Gone are the flat geometric shapes, replaced with stylish 3D characters which retain the same sharp angles as Thomas and his friends, but wrestle them into more complex forms. More importantly, out goes platform jumping and in comes stealth.

Yes, stealth, that most blighted of genres where the slightest wobble in the gameplay balance can be the difference between joyous thrills and howls of frustrated anguish. It's here that the design-first ethos pays off.

Bithell has made no secret of his debt to Metal Gear Solid, and it shows in the simplicity of his stealth mechanics. Guards have rigid paths and clearly delineated fields of vision. If you're outside of those sweeping cones, you're safe. There's no doubt, no ambiguity. Even if you are, technically, standing right in front of a guard, provided his eyesight ends before the spot you're on, you are invisible. Does it make sense? In reality, no. In a game? It makes perfect sense. Rules. Design.

You're playing as Robert Loxley, a sort of Robin Hood for the Occupy generation. He's come into possession of the titular Volume, a military training VR device that he repurposes for his own propaganda, live-streaming his virtual burglaries of the rich, corrupt and powerful in order to inspire the populace into rising up against Gisborne, the brilliant and malevolent private sector bully who has taken over Britain and is running it as a corporation.

Each level of the game's core storyline sees Loxley attempting to grab every precious gem before heading for the exit. There's a Pac-Man style purity to the idea that is overtly acknowledged in one of the later stages. Yet each level then breaks down into even smaller challenges, with perfectly placed checkpoints slicing each stage into distinct environmental puzzles to be navigated.

Control is slick and crisp, as you'd hope in a game that is all about precise and decisive movements. Your footsteps don't make a noise, so there's no need for the redundancy of having a sneak button in a game entirely about sneaking. One button sticks you to the nearest wall, another helps you slip around corners. That's really all you need in order to be stealthy in a game, and Volume sticks with what works.

On top of that you have a selection of gadgets and tricks, introduced at a sensible pace. The most basic is that you can whistle or interact with scenery objects like toilets and taps. Guards within earshot - depicted, again, with a simple and unmistakable radius - will come and investigate, creating gaps for you to slip past.

Later on, you get the bugle, a wonderful toy that can be bounced around the level with a satisfying ping, using an angular aiming tool familiar from any snooker or pool game. When the bugle lands, or earlier if you prefer, it emits a noise to lure guards away. The mute, meanwhile, does what you'd expect, allowing you to run across noisy floor plates without a sound. The mute also speeds up your movement while active, a subtle side effect that makes all the difference in some skin-of-your-teeth scenarios. The oddity, on the other hand, is perhaps my favourite - an object so fascinating that enemies are compelled to stare at it, oblivious to any noise or disturbance for the duration. It's incredibly useful, but also has a Douglas Adams absurdity that is especially fun.

There are more, but part of the joy is in the way the game introduces them, lets you play with them, and then leaves you to understand how they might be used in the future. Some stages even offer a choice of gadgets - you don't carry them between levels and can only ever have one equipped - so the route to success is not always prescriptive.

Each tool has a similar function, since your needs are so primal - distract, avoid, hide. The differences are minor but require satisfying tactical thought. Many are the situations that would be easy with an oddity, but seem impossible with a bugle. Working out the way to progress leads to many a happy "Aha!" moment.

Progress isn't insultingly easy, but nor is it punishingly frustrating. The smart checkpointing makes a big difference, but levels are rarely designed to take more than a few minutes to beat - once you know what you're doing. Each one has a par time and a leaderboard, as this is a game where speedrunning is very much part of the DNA.

At a purely mechanical level, this is the video game as a well-oiled machine, where every feature and function just makes sense, and where you never feel like the game is going to punk you with cheap tricks or flaky AI. You always have absolute confidence in how the world works, meaning the only rogue element is your own skill - or lack thereof.

The game's weakest element, somewhat ironically given the success of Thomas Was Alone, is its story. Or, rather, the way its story is presented. It's one thing to have narration over the top of a platform game, but Volume requires a different, deeper level of engagement, with the result that I found much of the game's dialogue washing over me rather than sinking in.

It's not that it's poorly written. It's actually very witty - if a little precious at times - it's just that here the story kind of sits on top of the game, rather than slotting neatly into its spaces.

It's not as if there's much to complain about in terms of acting. Danny Wallace returns in a similar role to his BAFTA-winning narrator from Thomas Was Alone, voicing Alan, the AI in charge of the Volume simulator, with a similar mixture of beguiling personality and winking irony. Andy Serkis, Gollum himself, makes for a fantastically menacing Gisborne.

The decision to use YouTuber Charlie McDonnell as main character Loxley is harder to warm to. His performance is a little too drama school, his voice too thin and reedy, to comfortably fit with the game's satirical political undertone. It doesn't help that some of his random interjections veer too far into the realm of Tumblr whimsy, cribbing David Tennant's "allons y" cry from Doctor Who, and referring to "the internets" in a cutesy fashion. To its credit, the script does acknowledge this and makes his lack of gravitas a part of Loxley's character, but it remains a weak point in a crucial area.

The story mode is really only the appetiser, though. Volume's long term appeal comes from the community, and the robust level editor that makes it quick and easy to build your own locations, populate them with enemies and set their behaviours. Creating a really good level takes time, inspiration and patience, but all the tools you need are intuitive and accessible. As with the gameplay itself, everything clicks together with Lego-style neatness.

It's this clarity that keeps impressing me. So many games are cluttered these days, piling features on top of busywork. Volume isn't short of great ideas, but it delivers them gracefully, one at a time, layering simple concepts on top of solid mechanics to create the sort of organic gameplay experience that seems effortless. Its rules are clear, the edges of its world and your place in it clearly defined. Everything you need to know is on show. While Volume may be more complex than Thomas Was Alone in almost every respect, it's still the work of someone who understands the value of simplicity.