Wattam review - a Takahashi joint through and through

Poop art.

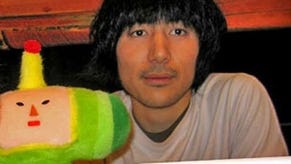

Keita Takahashi remains singularly unconcerned with concepts such as target audiences and player retention. When asked what he's aiming at with his games, the answer is, simply, "fun". Subsequent questions are likely to be met with a shrug. In light of this, the story of Takahashi's hit Katamari Damacy feels like a happy accident, precisely because he embodies the spirit of an independent creator unbothered by commercial constraints. Takahashi designs small experiments, brightly coloured toys limited in function, but fun in the moment. Easy to pick up and put away. It's a mindset he shares with Funomena, who collaborated with him on Wattam and who make games such as Luna and Wooorld with the same colourful, inclusive appeal.

Wattam feels like a collection of the things Takahashi found fun in the moment, several simple elements loosely connected by a theme. It begins with you taking control of the mayor, a green cube with a face wearing a bowler hat. The mayor is all alone on a floating island, until suddenly he claps eyes on a new friend - a stone! "Welcome back, stone!!" it says, and in this vein it continues. Your task is basically to repopulate a number of islands, each representing a different season, with any odd thing people usually associate with each.

"Repopulate" might be a generous word, as it implies you know what you're doing, when really you just do what Wattam tells you to, following its special brand of Keita Takahashi logic. Here, each usually inanimate object takes a life of its own, and you play with all of them. Each has their own music, which is a nice idea on paper, but relatively chaotic in practice as you switch between characters. Some have a use and some don't - the mouth for example spends its time chasing its food friends only to gobble them up and then poop them out from a thankfully unexplained orifice. Congratulations, you have just reintroduced one type of poop into the world! (There are several.) You can then take control of the toilet, which gleefully flushes the poop, turning it shiny and golden. If you take control of a tree, it will suck up another character Kirby-style and bring it back as fruit. Or maybe you want to go 'go kaboom' - then the mayor lifts his hat to reveal a bomb underneath that will explode into bright smoke and propel him and everyone nearby into the air. Why? Just because you can.

Each seasonal island has a rough gameplay theme. Upon arrival, there is a tree to plant and a few tasks to finish. Each quest, whether that's reuniting a sushi um with her fish roe children or rescuing a book assaulted by adoring stationary, is completed with only the small set of actions at your disposal - look at something and watch what happens, interact with another character, climb something, take someone by the hand. Wattam uses words sparingly, mostly showing you where to go, rather than telling you. Since gameplay rarely involves more than pressing a button in a specific location, everything is easy to follow, which generally makes it a great game for young kids.

I say generally because currently the physics engine and camera controls fight you every step of the way. Wattam uses shoulder button camera controls for camera turns and zoom on the PS4, the dinosaur of camera controls straight from the PS2 era. Sometimes the camera will move without your doing, and it always makes matters worse. With all the sentient beachballs and bottle caps milling about on each platform, the framerate can drop to a stutter, there's often something blocking your view, and selecting the character you want to control is imprecise and downright fiddly at times.

Climbing may or may not work, not only because the camera can randomly swerve away from what you're doing, but also because a character may simply not find a hold or refuse to move despite already being attached to a surface. On the flipside you may accidentally climb everything and everyone whether you want to or not. Characters lay down on the ground on more than one occasion, helplessly spasming with happy smiles frozen on their faces, until I restarted the game, or launched themselves into the air or below the earth, never to return, which is particularly annoying if it happens to a quest-giver. To top it all off, Wattam crashed several times, going so far as to crash my entire console at one point.

Calling it a spiritual successor to Katamari isn't that far off, because it's game that deals with household items and the micro-cosmos they represent. A seashell isn't just a seashell, it's something kids bring back from a fun day at the beach. The bowling pin is perhaps reminiscent of an afternoon at the bowling alley with the family, and as the nose you can enjoy the different smells of the season. In his own voice, Takahashi said that he's always trying to make a game that shows how ordinary life is great. Wattam shows an appreciation for the small things we take for granted, and it has you piece together a whole universe of them. It imagines the panic a balloon might feel at being released into the sky with the same gentleness Toy Story has for toys fearing abandonment, and all you really do is help others and do fun things like dance around in a circle. There is a story that explains why everyone got separated in the first place, but again the overall feeling of kindness and appreciation, of restoring a universe, is what really matters. It's warm, downright soft at times, definitely homey.

Wattam uses a combination of light gameplay and love-it-or-leave-it humour I associate with Keita Takahashi and like, but it's more of a Noby Noby Boy 2.0, a game so simple and nonsensical it sometimes makes you wonder what the point is. If his previous games weren't for you, this one, perhaps a humorous experiment more than anything, certainty isn't going to change your mind. While this and the technical issues prevent from unreservedly loving it, I still enjoyed Wattam, simply for delivering emotionally, if not on a technical level.