'We came in a little tentative' - the Coalition talks life after Gears of War 4

Rod Fergusson and his team talk working within Microsoft, preparing for Xbox Scorpio and making Epic's formula their own.

How do you revive a property as venerable as Gears of War, having prised it from the grip of the original developer and thrust it into the palms of a fledgling team? For starters, you act indie.

"When I joined, I tried to bring with me an independent development mindset that I had from working at Epic, at Irrational and so forth," recalls Coalition studio head Rod Fergusson, the genial yet hard-nosed Gears veteran who, post-Bioshock Infinite, has something of a reputation for being able to wrestle difficult projects into a shippable state. "Microsoft's a large organisation, and there are a lot of benefits to being part of a large organisation, but one of the things is that you can sort of get lost in the process, the bureaucracy, and I didn't want that.

"I felt like we had to get into an entrepreneurial spirit," he continues. "To be successful in games I think you have to have a 'get shit done' attitude, so we actually started a 'get shit done' program, where team mates can nominate each other for getting shit done, with T-shirts and a monthly 'get shit done' hero. All this stuff is just a way of reinforcing the culture that I want to have, which is that you don't get caught up in red tape. How would you solve a problem if this was your business, if you were an entrepreneur or a start-up?"

As part of this focus on letting individual team members thrash out their own approaches and solutions, Fergusson also called for a reorganisation of The Coalition's hierarchy (he doesn't mention whether layoffs were involved). "When I started there were a lot of people talking to producers, because we're a producer-driven culture, and I went with what I knew, which is people reporting to people of the same discipline, instead of into producers. You get proper mentoring that way."

The studio's relative remoteness from Microsoft's corporate hub - it's based in downtown Vancouver, with the Pacific Ocean twinkling at one end of the street and mountains looming at the other - has proven conducive. "We're a three hour drive from Microsoft in Seattle," notes Fergusson. "Which is close enough that I can get there same day, feel like I'm part of Redmond, part of Team Xbox, but just far enough that we feel we have that independence, we can do what we want to do and not be under that umbrella all the time."

As I gaze around the Coalition's cavernous office, its workspace facades theatrically dusted with Gears memorabilia, its desks lined with dour-faced QA staff, I can't help wondering about the possible side effects of this efficiency drive. Rewarding initiative is all well and good, but letting your creators pick and fight their own battles shifts the stress of project management from organisations to individuals.

Still, if Fergusson's invocation of an "entrepreneurial spirit" is slightly suspect, there's no denying that The Coalition has gotten shit done. On the strength of 15 hours with campaign and multiplayer, Gears of War 4 is a deft if not quite thunderous return, a game that knows its heritage and also, crucially, where that heritage can be elaborated upon. And if the three years since Microsoft acquired the IP from Epic have been a journey - a journey that has run parallel to the closure of Lionhead, Xbox Studios and Press Play, among other major tectonic shifts - all the staffers I meet during my tour of the Coalition's headquarters seem genuinely delighted with their lot.

I am, of course, seeing only who and what the circling PR folk want me to see, but there's little sense that the Coalition has suffered for its transformation from an IP incubation chamber (then known as Black Tusk Studios) to Microsoft's in-house Gears of War team. The collective verdict is that as both a narrative universe and a bundle of systems, the series is complex and enigmatic enough to keep a hungry young developer preoccupied. "The core mechanics play is so deep," enthuses multiplayer lead Ryan Cleven. "You're combining really sophisticated horizontal platforming, really deep movement play, with aiming. Other shooters are about strafing, maybe a little bit of jumping and then aim-play. But we have a very detailed movement system, almost like in a fighting game, plus shooting. You put these things together and you get a really deep potential skill gap."

Art director Kirk Gibbons, meanwhile, admits surprise at being able to steer the tone of Gears 4 away from the original's brick-thick machismo (though this is still a game with biceps you could park a Hummer on). "I did think it was going to be more of that kind of thing," he says. "You think of all those old characters. But we really went on an adventure, we took some risks with the new cast, and I think we've really delivered."

Reviving Gears of War's craggy Marcus Fenix as a playable character alongside his son JD has acted as a pressure release valve of sorts, allowing The Coalition to engage in a metaphorical and comically fractious, father-son dialogue with Epic's work. "I love that interplay between the young optimistic crew and the grizzled old vet," Gibbons remarks, perhaps mischievously. "I think that interplay creates something fresh."

The project's biggest hurdle has been rebuilding Gears of War's systems to take advantage of Unreal Engine 4, a process that began with the Ultimate Edition remaster in 2014. The two generations of middleware aren't compatible, so The Coalition was obliged to go through the entirety of Gears of War 3's codebase - "about half a million lines of code", estimates technical director Mike Rayner - in order to make use of modern techniques like high dynamic range lighting. "We had to rewrite the AI from the ground up, we had to take all the models and rebuild them from the ground up, we had to do all the weapon tuning from the ground up," recalls creative director Chuck Osieja. "All the movement - we built a tool that allowed us to do pixel by pixel comparisons between Gears 3 and what we were building, to make sure that it felt spot-on before we started."

As the studio's leading Gears guru (though not its only former Epic employee - there's also cinematics director Dave Mitchell, multiplayer producer Jonathan Taylor and quality assurance director Prince Arrington) Fergusson has lent his eye to every aspect of the project, wading in at times to course-correct, and paying out a little rope at others. "It was a challenge because we had to be careful," he says of the game's interplay between JD and Marcus. "We wanted JD to be the hero, but we wanted that friction, and everybody loves Marcus, so if Marcus doesn't like JD, people might take Marcus's side and say 'yeah, I don't like that kid'. Which is hard to have, when he's your protagonist. So we had to walk that fine line of how you create tension without kind of alienating JD too far.

"One of the earlier ideas that I shot down immediately was 'oh, every time you have a rebellious child, he'll call his dad by his full name'. And I was like 'no-ooo, we're not doing that.' Because everybody will be like, 'hey, that kid's a dick! I don't want to be him'. It was an interesting tightrope to walk."

The same is true of the new game's gunfights, which alternate between mid-range rifle play and shotgun duelling, give or take the odd spree with a power weapon. It's a familiar mix, but The Coalition has inserted a few colourful toys of its own devising, mostly in order to extend a well-tried concept or clarify a tactic. "If we're going to make new weapons up, where are the openings in this framework we can target to make sure we don't overlap or break anything?" comments Ryan Cleven. "The Embar rifle is a great example - we think it's a little higher-skill than the Longshot, so cool, that goes in. With our submachine gun, the Enforcer, we had to be very careful about how to build that so it didn't shadow the shotgun play or support play. There's a very small spot for where that weapon can exist."

There's a lot of this kind of delicacy to Gears 4, as brash and bone-headed as it may appear on the surface. The iconic Gears sprint or "roadie run", for instance, has been reworked to look less artificial, though it is functionally identical. Rather than popping straight from erect to a business-like waddle, character models now turn and sink into the movement as they run. "It didn't change for four games, and now it has, and I guarantee you nobody will notice that it's changed, because it feels right," says Chuck Osieja. "Rod said that, for years, it was a temp animation they put in which they could never improve on, and part of our goal was to do that, but not change how it feels. The way it acts and reacts is exactly what you'd think, but the feel and animation are different."

The obvious rebuttal to this is that if nobody will notice, what exactly is the point of making the change? While they maintain that the devil is in the detail, Fergusson and Osieja both concede that Gears of War 4 is a little on the cautious side in terms of its core mechanics. "It's hard to [take risks] when you're taking over the franchise for the first time," protests Osieja. "We have no credibility. Outside of Rod and a couple guys we brought from Epic, none of us have made a Gears game before. Who the hell am I when it comes to Gears?"

Fergusson confesses that he had anticipated more pushback from returning players during the initial reveals and the Xbox Live beta. "I was expecting to have to defend ourselves more around whether we were credible as Gears of War maker. But people accepted it really fast, and I was like 'oh crap', and I had to pivot to 'look at all the new stuff!'" It was important, he adds, for The Coalition to "show respect" for the series before starting afresh - an evidently well-rehearsed choice of words that recasts Epic's trilogy as a war veteran, to whom due reverence must be paid.

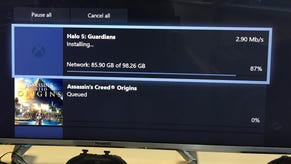

As a whole, The Coalition seems less like an indie at the edge of Microsoft's domain than a product of the conservatism that defines much of Microsoft's line-up. I think this reactionary tendency is often exaggerated - go play Halo 5's Warzone Mode or Super Time Force if you think Microsoft's full or timed exclusives are just the same three tunes on repeat - but it's there in Gears 4's choice of a generic Caucasian beefcake as lead character, and it's there, perhaps, in the writing team's gentle refusal to discuss the politics of a fantasy world that has been stripped of fossil fuel.

"For me the message is that society found a way to live well without relying on what they had previously, and it's just part of the background fabric of the world," observes narrative director Bonnie Jean Mah, adding that she doesn't want to "hit people over the head with a metaphor". With hundreds of millions of dollars hanging in the balance - to say nothing of countless late nights, arguments, uncertainty and heartache as features fall beneath the wheel of deadlines - this timidity is understandable. But I think it's also why Microsoft's bigger titles often fail to set imaginations afire next to, say, a Metal Gear Solid or a Last Guardian, for all their fundamental competence and complexity. The elephant in the room, of course, is the studio's previous project, a mysterious new IP that was teased at E3 2013, then shelved not long after Microsoft bought the rights to the Gears series.

Team members are adamant that the publisher hasn't interfered with the project's direction in any significant fashion. "There was no central mandate from Microsoft to make this game one way or the other," insists Ryan Cleven, when I ask whether selling packs of ability and personalisation cards in the game's Horde Mode reflects Microsoft's input. "The development cycles on this game are long, and it's something that very early on we were interested in."

Fergusson, meanwhile, concedes that for a first party studio, "there's always that give and take" with the parent company. "It's sort of, you push the platform by asking: 'these are the kinds of things I want to do in the game, can the platform support that?' And you also get questions like 'hey, these are our platform directives, as a first-party studio, can you help light that up on the platform?' But even as a second party we had that. When party chat first came online on Xbox 360, they were like 'hey Epic, can you make sure that party chat is implemented?' We were helping to support the platform initiatives there too."

If The Coalition has pulled its punches in places, the upside is that it has plenty of material left over for a sequel, now that the hard labour of learning and remastering Epic's formula has been done. "If everything went sideways tomorrow we could hand it off to somebody else and they would have a really good understanding of how to build a Gears game from the ground up," says Chuck Osieja.

"Deconstructing and archiving all this stuff - it was not only good for us, but every time we brought somebody in we could put all that documentation in front of them and say: 'OK, this is why cover is laid out the way it is, this is why these weapons exist and these are the roles they fill. When you think about enemies they need to fill one of these three roles, because that's what happens in a Gears game.' We haven't had the chance to reflect on all that yet, but now we're near the end, able to think about what we're doing next... I's how quickly [new hires] will be able to get up to speed because of all the groundwork we've done."

"We came in a little bit tentative because we felt we needed to prove ourselves," adds Fergusson. "When I started here there were lots of great innovative ideas that I felt were just too outside the box, for a studio that hasn't proven itself. There's a lot of room now to push the campaign further, mess with the formula a little bit, because people will just see it as the natural growth of our game, versus messing with it in order to mess with it." You can expect more immediate change in terms of the multiplayer, which echoes shared-world shooters like Destiny with a rotating map selection (including free DLC maps) to give players a reason to return regularly. Its evolution may be strongly affected by the game's success or failure as an eSports platform - there's a new mode, Escalation, which is designed specifically for tournament play.

"I always say that eSports can't be bought, it can only be earned," observes Fergusson. "You can't put down a $20 million prize pool and fill an arena - you can fill an arena because people care about your game and its players, and that's something you have to earn over time." The new take on Horde Mode may also undergo dramatic shifts. As an upgrades-driven wave survival mode, it's already a very modular structure, built around ability slots, classes, fortifications and specific mixtures of enemy types, so there's plenty of opportunity for expansion "now that we have the plumbing down".

When I went to see The Coalition, it was well into the unromantic final throes of development, whittling away at the bug list in preparation for certification; as I write these words, Gears of War 4 is winging its way to reviewers. It's an emotional time for the studio's younger members, of course, many of whom have never shipped a game of this scale before, but a particularly poignant one for Fergusson, seeing his old game reborn in the hands of a different generation.

"Early on I sent a couple of concepts to [former Gears of War art director] Chris Perna, because he had his own ideas about where things should go," he recalls. "It was kind of a back channel email. 'What do you think of this monster?' And he was like 'Yeah, that looks really cool'. And I was like 'OK! Good!' You get a bit reliant on people, having Chris, Lee Perry, all those guys, you become dependent on them. They were part of its genesis, and you end up thinking: how much of this is you, how much of this is them?

"And what's been great is to come here and get new collaborators, to work with Chuck and Mike Rayner and Kirk and Ryan. I've found a new set of people who I can have that creative outlet with, have those ideas come in and have it still feel like Gears."

This article is based on a trip to Vancouver to The Coalition's offices. Microsoft covered travel and accommodation expenses.