Westwood's Blade Runner is an all-time classic in danger of being forgotten

Hard to replicant.

Some of the brightest lights of 90s gaming are beginning to wheeze, croak and lose some of their sparkle. But just as they take a step towards retirement, they're given a new lick of paint and booted back through the door in remastered form. Or kept upright by a battery of emulators and plastered across the front page of GOG. We're truly spoilt. But what happens when a golden oldie can't be revived?

As a new Blade Runner film arrives in cinemas today, the video game that shares its name should be front and centre on GOG. But short of rebuilding it brick by brick, Blade Runner will never get a facelift or a new home. In 2003, a terabyte of data was lost. The source code went down the drain, and ever since, Westwood's magnum opus has been buried beneath the weight of time.

If you're lucky, you can still pick up an original copy on eBay or Amazon. Inside the enormous cardboard box, you'll find four discs to be fed into your drive. Getting it to work isn't particularly straightforward - for that you'll need a patch and a fair wind to have it up and running on a modern operating system.

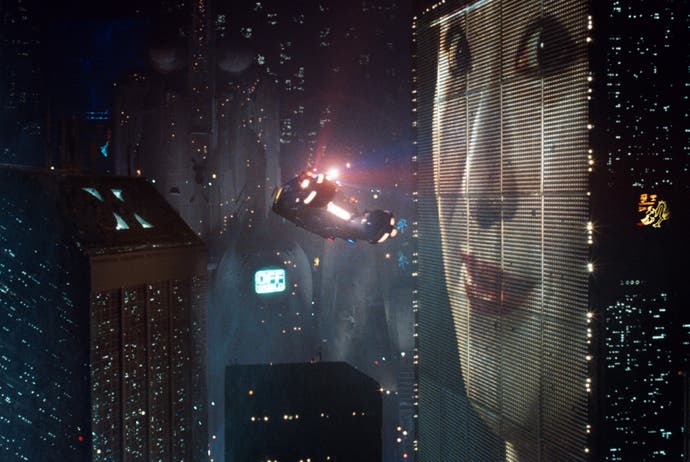

The effort is worth it, though. As Ray McCoy steps out into the everlong night, the collar of his trench coat turned up against the rain, Blade Runner exudes a quality all the greats have: a sense of timelessness. It's a point-and-click adventure game of the highest order; pitting a single cop against humanoid androids fighting the bureaucratic machine. Its years in cyrosleep have maintained its good looks, but in many ways, Blade Runner has always been ahead of the curve.

Take its scope. Developers Westwood brokered a deal in the mid-90s to tell their own story within the shared universe. The problem? The script they had written internally was functional, linear, constrained, and the goal was to weave a narrative that adapted to the way you played. Why not make a choose-your-own adventure set in the Blade Runner universe?

David Leary, a writer and occasional programmer, was drafted in to do just that. He took charge of game design and helped write a programming script that changed everything. Quite simply, a programming script that would roll a dice. "Every time a player started a new game," Leary recalls, "the dice would pick whether characters were replicants or not." Now, every time McCoy would step out into the everlong night there would be no telling - bar a few constants - who was aligned with whom. And besides, whose side were you on anyway?

"Creating the code was not that technically difficult," Leary admits, "but the challenge was to make sure the pieces wouldn't fall apart." Leary began adding to the story, creating a branching narrative he tried to push "as far as possible", one that included a dizzying 13 endings and various diversions along the way. Once the endings were sorted and the opening was done, the spine was in place, and Leary made use of index cards to keep track of the branching threads in between. To make sure the game didn't break, playtesters logged thousands of hours.

In my recent playthrough, there was only one instance where Blade Runner's illusion of a free-form world snapped: a small snippet of dialogue that didn't chime with the events that had occurred in my story. Everywhere else, that illusion was faultless, lending any moment you choose to draw McCoy's gun a sense of serious consequence. Though you never need to pull the trigger, doing so will alter the story inexorably and affect the ending you see.

Blade Runner is a breath of fresh air for adventure games. It uses atmosphere to make give its world weight, with its constant slashing rain and a whistling wind, while keeping the interface tactile and light. There are no contrived obstacles you need to dig into your inventory to solve. Simply put, the cursor turns green when you can talk to someone, or when you can pick up a clue. "One of our design pillars was to make you feel like a detective," Leary remembers. "To that end, we wanted to focus on exploring crime scenes and doing investigative work, and reconciling bits of information you discovered with your conversations with other characters." The team decided early on that "traditional" puzzles wouldn't aid that.

"One of the challenges we faced was how much game versus how much interactive story were we trying to hit," Leary remembers. To add flavour, the Esper and Voight-Kampff machines were woven into the game; nods to the original film. "The Blade Runner Partnership" - holders of the IP - "gave us an awful lot of freedom to play in their world. We were motivated to be loyal and we bought ourselves a lot of freedom by having this parallel story and being very careful not to mess with the movie itself," Leary says.

The team channelled the movie's art style, creating a future Los Angeles that felt alive. In McCoy's bedroom, a blue haze spills in from the city beyond. In the sewers, steam billows from rickety ventilation shafts, while in the Chinese district, the roads sparkle with the neon sprawl. High in the Tyrell Corporation a warm sun catches the thick, gold-nugget tiles. Deep in Tyrell's depths, a spider-like console leads to a dome sat squat on its haunches. All these touches are authentic Blade Runner, and every pre-rendered scene is staged at a careful angle as if being viewed from the director's chair. Despite the limitations of 1990s technology, Westwood established a filmic presence.

Actors from the 1982 original lent their voices as characters new and old were staged throughout the story. James Hong reprised Dr Chew. Brion James returned as Leon. But not Harrison Ford. Perhaps he had gotten a whiff of the 1985 Blade Runner built for the Commodore and balked at its run-and-gun gameplay and lousy graphics. Perhaps he just doesn't like games. Rumour has it he's in the Roger Ebert camp on that front. Westwood had fun nonetheless, referencing Deckard and concocting ways to have McCoy's story overlap with the film's.

Blade Runner shipped in 1997 as a definitive canon entry and sold a million copies to boot. Today it sits in that rarefied strata occupied by the likes of Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay and Alien: Isolation; games that perfectly capture the essence of their source material but blaze their own trail.

Despite outselling 1997's other big adventure game by 3 to 1 (The Curse of Monkey Island) Westwood didn't recoup enough money to consider making another. Then, in 2003, EA came calling and Westwood packed up shop as the code slipped through the cracks. I asked Leary what he'd do over if he had the chance. He talked about improving the Voight-Kampff sequences and remaking the character models. "They were built out of detailed slices called voxels but at the time, hardware didn't support pushing those models as far as we wanted to. We struggled with this right up until the end and it was a compromise the team felt bad about."

Today Leary is stationed at Playful. He's dropped his game design duties and heads up production on Creativerse, a sandbox adventure available on Steam. I tell Leary he hasn't left behind his roots, and he laughs. "Westwood was my first gig, believe it or not, and it was a lucky break." Making the game, he got to work with veteran Jim Walls, a former cop who shaped Police Quest. Then there was Michael Legg, the Midas programmer, and Westwood co-founder Louis Castle.

The upcoming Blade Runner film has Leary excited because, like the rest of the Westwood team that brought Blade Runner to PC, he adores the IP. And passion is everything in the chaotic and collaborative world of games development. It's the difference between good and great, memorable and timeless.

Ironically, time has not been on Westwood's side. Sheer bad luck robbed its magnum opus of longer in the sun, but as I discovered, Blade Runner can be coaxed to life on modern PCs. In fact, it shines there and stands tall as a superb reinterpretation of a classic film franchise. The only downside is a sizeable one: getting hold of a copy. Sell your cat, mortgage your house - just dredge up those discs any way you can.