What is Indie?

DIY developers discuss what it means to go solo, and whether the label really matters.

Back in the early '90s, the definition of 'indie' music went under a transformation. What had started as a tag for any act that released music without the help of a major record label became a way of describing - and selling - a sound and a lifestyle. Once it was all about crudely recorded cassette tapes and direct, intimate fan interaction; today it's Coldplay, with all the corporate fixings.

And now a similar evolutionary shift seems to be taking place in the games industry. Whereas not much more than five years ago the indie game was solely the domain of hobbyists and modders, now, thanks to the speedy ascent of Steam, iOS, XBLA and PSN, indie is everywhere and, increasingly, it's big business.

But as it grows, it becomes harder and harder to pin down what an indie game actually is. There are some games and developers that everyone would agree are resolutely 'indie'. Minecraft and Mojang; Super Meat Boy and Team Meat; World of Goo and 2D Boy. But what about, say, Journey? It might carry all the stylistic trappings of an indie game, but developer thatgamecompany was funded by Sony. Or, to take it one step further, what of Epic? It's self-funded and answers to nobody, but few would label Bulletstorm or Infinity Blade 'indie'.

It's easy to say 'who cares? A game is a game'. But, just as it did in the music biz, the concept of 'indie' serves a higher purpose. It's an ethical and stylistic flagpole that many gamers and developers passionately pin their colours to, an important community-building tool and a useful descriptor in conveying exactly where an unfamiliar new game is coming from. Some clarity, therefore, might be helpful.

So, what is the dictionary definition? Speaking to a number of developers positioned at various points along the indie spectrum, it quickly becomes clear that it's a term creators find just as confusing as many players do.

Jeremiah Slaczka is CEO and creative director of 5th Cell, the 70 staff-strong developer behind Scribblenauts, iOS platformer Run Roo Run and forthcoming XBLA shooter Hybrid, among others. It's worked with major publishers before but is 100 per cent independently owned and operated. Is it indie?

"I'll say one thing: we'll never sell our company and we have no investors. Nobody owns equity in it but us. There are plenty of indies who say they're indie but they're owned," says Slaczka proudly.

"I don't even know if the word indie is defined yet," he continues.

"Would you say Hard Reset is an indie game? I would. No equity, no investment, all their own tech, built their own engine, marketed their own game. But just because they did an FPS with pretty graphics they're not indie?

"Is it an image thing? Is it an arthouse game, is that what indie is? Is it smaller teams? Simple gameplay, simple graphics, small teams - that seems to be the definition of indie right now. But I don't know if that's true. I don't know if I agree with it, but I don't have a better definition either."

Robert Boyd, co-founder of the two-man studio behind breakout XBLIG hits Breath of Death VII and Cthulhu Saves the World is rather more confident in his definition.

"An indie developer is an individual or small group that is not owned by another company that makes games," he states. "An indie game is a game made by an indie developer, simple as that."

That "individual or small group" qualifier seems unsatisfactory though. Jumping back to the music world, fiercely self-sufficient Canadian art rock collective Godspeed You! Black Emperor regularly boasts more than 10 band members on stage at one time and is part of a wider collective that encompasses five or six other acts, but nobody would dare question its indie credentials.

Indeed, Epic Games is keen to argue that size doesn't necessarily matter.

"We're big indie, I guess," says co-founder Mark Rein.

"We are an independent company. We make games and we publish them ourselves through iOS so, yeah, Epic still embodies the indie spirit. There's no question.

"I don't think anyone thinks of us as an indie because we make games for Microsoft," he concedes. "But we think of ourselves as an indie. We own the company, we make the decisions about what we're going to do and we work very hard to please our consumers."

When pushed to define exactly what he means by "indie spirit", Rein replies, "A little bit of gold rush mentality. Look! The grass is greener on the other side of the fence! That sort of thing."

So, innovation, ambition and hunger? Is that what being indie is all about? Kellee Santiago, co-founder of Sony-funded Journey and Flower developer thatgamecompany, agrees that a developer's goals are more relevant than its financial status when it comes to discerning who is and who isn't indie.

"Indie is when you are innovating in some way on how games are made," she says.

"That can either be creatively, in that you're investigating different subjects and different ways of making games, or from a business perspective, with how you're financed or distributed. And in some cases that's happening simultaneously.

"We've been in a development deal with Sony so I've always felt blessed that we continue to be counted among independent studios, even though from a festival and financial standpoint we don't qualify.

"But I think it's because we have been empowered by Sony in many ways to make all the decisions surrounding our games and we use that to continue to do things we think we couldn't do anywhere else."

She goes on to argue that, based on her definition, "a lot of seemingly large studios" such as Valve happily fall under the indie umbrella.

Adam Saltsman, the one-man indie workhorse behind genre-defining infinite runner Canabalt among many, many others, has a similar take.

"As a disclaimer, for studios that self-identify as indie, [indie] does specifically mean small budgets, teams of maybe one to four people, and working on strange and exploratory passion projects," he begins.

However, Saltsman adds that his own personal definition is rather different from that: an indie game is a project that is the sole product of a passionate creator, and one that's unfettered by outside forces.

"To me, an 'indie game' is just a game where the game makers didn't have to make compromises for anybody. They put their audience/work/ego first, they made something interesting and meaningful, and the audience can see the kind of personal touch of an auteur in there - whatever that might mean for games.

"It's being able to tell if a game was 'made with love'."

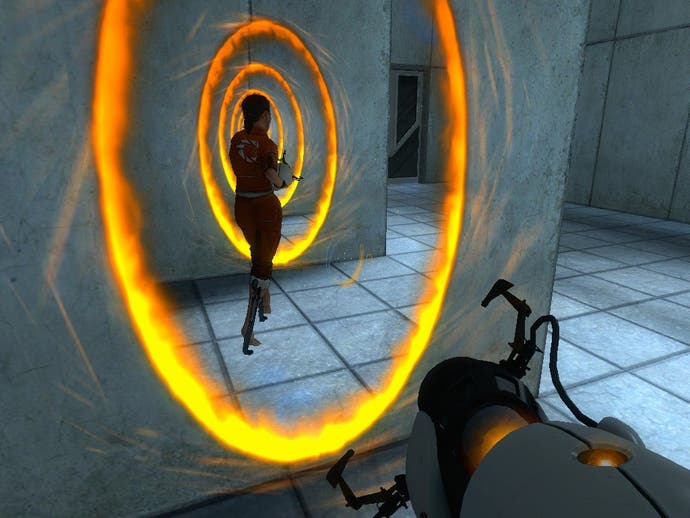

Echoing Santiago, he offers Valve's Portal as an example of a game published by a massive corporation that falls well within these parameters. On the flipside, Saltsman argues, there are plenty of titles made by small, penniless teams that are "really rote, derivative games pumped out either as a cash grab or as a way to keep people employed."

"It would follow then that an indie developer is just a person or group of people who sometimes make indie games," he concludes.

"To me Valve is totally an indie game maker, even though most of their games do have compromises, don't experiment as much, and most of their revenue comes from a gated distribution platform that they themselves administer.

"It is easy to forget how many indies moonlight as freelancers or contractors to help finance their passion projects. Steam - and UDK for Epic - seem like extensions of that practice, just on a larger scale."

Add all that up and 'a game made with care, affection and ambition, and unhindered by any kind of outside commercial or corporate agenda' appears to be the happy consensus.

However, as the indie game hurtles towards its Coldplay moment, the boundaries will continue to blur and it will inevitably become increasingly meaningless as a term. At that point, we will all need to work a little harder to weed out the titles that are true to these noble founding ideals.

Greg Kasavin, creative director at Bastion developer Supergiant, appears to have got a headstart on that. Instead of pigeonholing games with a "loaded, nebulous" tag like 'indie', he'd rather look to the story behind a game's creation for clues as to what it's all about.

"I don't like labels of any kind. I peel them off of bottles," he soberly tells Eurogamer.

"Speaking just for my own experience, Supergiant Games is an independent studio. This to me has a clear and inarguable definition, which is, we are a private company and do not have a parent company.

"Moreover, we have been able to self-fund our projects, which means we can make the games we want to make without pressure from publishers or other larger companies to steer our projects in different directions.

He goes on to argue that his game is defined by how and why it was made, rather than by some limiting epithet.

"The story of how we made Bastion was important to us, and I think the stories of how independent games get made are often interesting," he says.

"In our case it started with two guys who quit their jobs at EA, moved into a house, and started making a game. The team grew to seven and the resulting game was Bastion. It was a personal project for us and we wanted people to know that, because the context in which games are made can explain a lot about them, and why they're made.

"When we were at EA [prior to setting up Supergiant], we were inspired by games like Braid and Castle Crashers and Plants vs. Zombies. They were these really high-quality games clearly made with love and care by small teams. We wanted to follow in the tradition of games like that, and in my case it also reminded me of classic games from the '80s that were successfully made by small teams.

"How other people choose to label that work is up to them. I'm not concerned if we're called 'indie' or not, just as long as people know the facts."

It might not be the easiest answer but it's perhaps the most satisfactory. While the term 'indie' implicitly suggests that it's all about financial status, most gamers would agree that the indie scene is actually defined by its fierce creative spirit and contempt for corporate meddling. Maybe it is time to retire the word from our vocabulary. The games are starting to outgrow it, becoming something bigger, better and, with the traditional top-down publisher model showing signs of chronic decay, potentially much more important.