What we've been playing: Sir Clive Sinclair edition

In celebration of a true legend.

17th of September, 2021

Hello! Welcome back to our regular feature where we write a little bit about some of the games we've found ourselves playing over the last few days. This time: a bit of a celebration of the pioneering work of Sir Clive Sinclair, who has died, aged 81, and his magical machines.

If you fancy catching up on some of the older editions of What We've Been Playing, here's our archive.

Manic Miner

The ZX Spectrum was perpetual presence in my youth - seeded through my school days in the form of dog-eared copies of Your Sinclair, furtive exchanges of cassette tapes stuffed with illicit copies of Speccy games, mid-loading POKE cheats, and long nights studiously spend copying out code from Usborne's wonderful Adventure Game series - but the one defining moment of it all was Matthew Smith's 1983 gaming classic Manic Miner.

I distinctly remember waking up one night to the tinny drone of Hall of the Mountain King, belting out from our tiny back room, while my mother, bathed in the light of a squat grey portable TV, swore profusely at a tiny white man wearing a miner's hat. The discovery did somewhat spoil the next day's surprise - that our family now had its very first home computer in the shape of ZX Spectrum - but it was my very first introduction to the world of video games and a moment that genuinely would change my life forever.

And more than that, the single-screen platforming of Manic Miner itself - its riot of silly, insidiously unsettling surrealism set to that relentless classical music drawl - is still permanently etched into my brain. Truthfully, it's probably Miner Willy's next adventure, Jet Set Willy, that did the most lasting damage to my psyche - the horror of housekeep Maria's deadly pointing finger, the awful dripping presence in the Chapel, the game-busting bugs in the Attic, the irreversible descent into Hades, and the countless hours spend waiting on the beach for a boat to show up and whisk me to a secret island, as persistent playground whispers insisted it would - but before that was Manic Miner and the ZX Spectrum, the game and the machine that was, for me, the start of it all.

Matt Wales

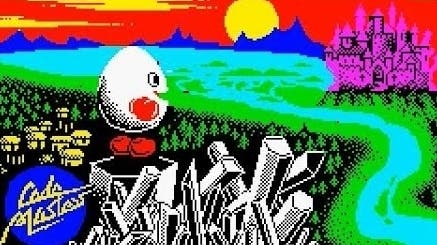

Dizzy

I've played (and still own) hundreds of Spectrum games, but for me the Dizzy series will always define that era of gaming. The first time I played the original Dizzy was at a friend's house and as soon as I heard that jaunty title screen music and laid eyes on that first screen with the cauldron and the spider in the tree, I was mesmerised. The world of Katmandu was ripe for exploration and, to my tiny child's brain, this was the closest I had come to being in control of an actual cartoon, rather than just passively watching one on the telly.

The screens and puzzles were so imaginative compared to other adventure games and this vibrant world engaged me in a way that none other had done at the time. The ZX Spectrum was my gateway into gaming, but without a doubt it was the Dizzy series that gave me my first proper experience of being deeply immersed in the fantasy world of video games.

Ian Higton

Turbo Esprit

What's striking about any Spectrum game from this almost 40-year vantage point is the ingenuity in working within the machine's tight restrictions - sound, graphics, memory - to produce something not merely entertaining but stylish and distinctive, whether in the surreal non-sequiturs of a Matthew Smith platformer or the sturdy isometric layouts of an Ultimate Play the Game adventure. But what I find awe-inspiring to look back on now are the games that fought, within that minuscule digital footprint, to deliver something even more intoxicating: freedom.

Turbo Esprit was one of those, a driving game (often cited as an inspiration for Grand Theft Auto) that let you loose on a whole city map, weaving through traffic, dodging pedestrians and chasing down bad guys in an armed and armoured edition of the Lotus sports car. The graphics were crudely figurative, but still delivered a primitive immersive thrill - the screen, bizarrely, offered a detailed in-car view of the instrument panel and a dramatic high-flying chase cam simultaneously - while the action balanced screeching 90-degree turns and clattering guns with waiting at traffic lights and watching your fuel gauge. It was a tiny world simulation, a teeming little playpen that seemed half-indifferent to the player, like it didn't really need you to be there to exist. What a privilege to visit these places, then and now. What a leap of imagination to create them.

Oli Welsh

The C5

Sir Clive Sinclair's gift to games was immeasurable, but of course it's one of his other famed inventions that's always fascinated me the most. Growing up in the 80s, the Sinclair C5 was the butt of so many jokes - underpowered, impractical and undesirable, it's widely considered as a failure. A few years ago I stumbled upon a C5 in beautiful gold and black JPS livery at a Lotus festival, and went away to discover a little more about how the Hethel outfit helped with the design and early prototypes of Sir Clive's three-wheeled wonder, and everything sort of clicked into place. Lightweight and innovative, the C5 was the kind of vehicle that would no doubt have tickled Lotus founder Colin Chapman too, and it would ultimately serve as a precursor to the inevitable rise of electric vehicles. Some 40 years ahead of its time, if you're ever lucky enough to see one today they still seem like a vehicle plucked from some rosy future.

Martin Robinson