How Edith Finch captures the weird reality of family life

House of leaves.

SPOILER ALERT! This article mentions key plot points in What Remains of Edith Finch, and I'd hate to ruin anything for you. Don't read on until you've finished a playthrough.

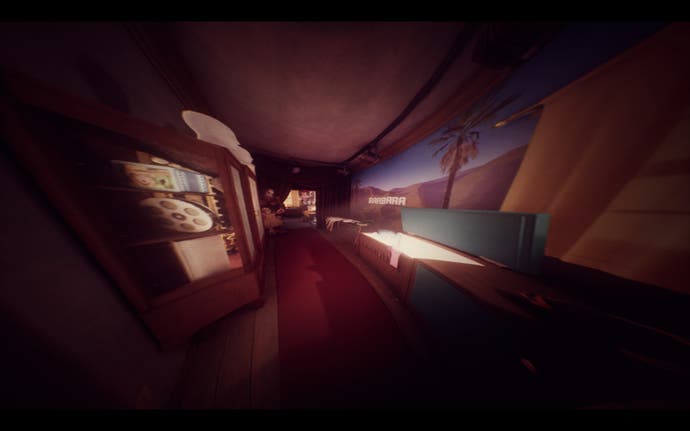

Most of the rooms are closed off on your initial foray into the Finch Mansion. The young narrator drops hints of what's to come as you peer through little fish-eye lenses set into each door in order to get a sense of the space beyond. And the space beyond is always worth seeing here, each room bright and themed and different. It's a bit like the early parts of a trip through IKEA, all those model lounges and kitchens, every one hinting at the diverse interests and personalities and needs of its imaginary inhabitants, a book laid open on a table as if the owner has stepped out and will return imminently, a quirky whisk on a counter as if souffles - do they require whisking? - might be on the agenda tonight.

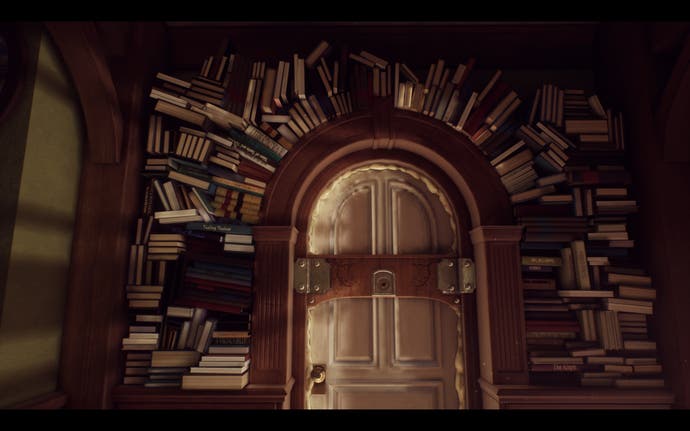

Also like IKEA, this is a world that comes with an optimal route. What Remains of Edith Finch, the game that is strung through the Finch Mansion, and strung so tightly that its traversable paths fairly hum with tension, offers a cat's cradle kind of journey that leads you back and forth through the history of a single family, one brilliant mechanical transition leading to the next. Each Finch, you swiftly learn, is unique, and each has left a unique room, eerily intact, behind them. Each Finch has died too soon and in unique circumstances, and each will tell you their story in a unique way, one revealed through the flicker-flack of smoky images preserved on the paper and celluloid disk of a ViewFinder, the next, perhaps, spread across the garish panels of a horror comic. The Finch Mansion is a house that is seemingly made of books - they are stacked in the hallways and, in one instance, gorgeously fanned around the door to the library in spoked shelves that seem to echo a rising sun. It is home to a game made of separate stories that come together to tell a single tale. A game that has nods to everyone from Mervyn Peake, in its geographically precarious isolation, to Salinger, and, with its rangy structural imagination, to something like the nested Russian doll narratives of Cloud Atlas, each story told in a different way and belonging, as it were, to a different genre.

The literariness does not stop there. These vignettes are glued together by architecture and by words themselves, glowing golden text that works like a breadcrumb trail but also adds a little playful heft, if playful heft is even possible, to the emotional detailing of the moment. It's a bit like the text in Winnie the Pooh, blown across one page by a brisk wind, scattered down another like falling leaves.

Despite all these allusions pulling in different directions, I have never played a game quite like Edith Finch: I have never played a game that manages to be so expansive and so compact, that uses its expansiveness in the service of making a series of small points with extreme precision. One Finch, for example, and I forget which one, works all day in a fish-canning factory, plucking salmon from a conveyor belt and feeding them into a guillotine. While he performs this monotony, however, he also escapes into a rich inner life in which he is a character in a video game - in a history of video games, in fact, moving from rudimentary dungeon crawler through to roving 4X. You must control both fantasy and reality at once, until one inevitably gives way to the other. It is astonishing stuff, the work of a virtuoso, and you play on and on through the fish-chopping, through the genre-hopping, just to see how far the game is willing to take it.

And it takes it all the way, of course. All of this to make the point, with devastating clarity, that a person may find at times that their connections to the real world are tenuous and liable to snap. This realisation is not delivered as tragedy, however. Or rather, it is delivered as a kind of euphoric tragedy.

And this, ultimately, is what has stayed with me about Edith Finch in the days and hours since I first sat on the sofa and watched my wife, who is a huge fan of the developers' previous game, The Unfinished Swan, venture up the Finch driveway and into this strange house where anything could happen and, at times, anything will. I am left not so much with awe at the design team's ability to marshall so many ideas, to fit so many quick-changes into such a small space. I am left with awe at the way that the team relies on fantasy as the best means of delivering something that feels, in the end, singularly realistic. This is the rare game revolving around something that is real, that is human and important. The rare game that is about the thing most of us have at least some experience of, but rarely expect to see meaningfully explored in a game. Edith Finch is a game about family.

The pseudo-Bartleby in the fish cannery, the artist in the attic who has managed to paint himself, rather literally, out of reality, the boy on the swing who sought to join the swirling, romantic skybox that roared overhead, these stories are lurid and often weird because memory is lurid and often weird. They are extreme and unlikely because the ways we tend to tell stories about the people who are close to us often render these people in extreme and unlikely ways. Edith Finch's endless geographical complexity hints at the sorts of isolation that can occur when family members live together in extremely close quarters, while its narrator, returning to the mansion after a long time away and nervous yet determined to make sense of her own lineage, perfectly captures the sense of distance, of sad, critical chilliness, you can bring to your own family at the point you at which you are going to be adding to it.

It's a wonderful, unmissable experience whichever way you approach it, in other words, but it's been particularly suited to the kind of backseat gaming I've enjoyed with my wife at the controls. I've been able to make out the smaller details of the worlds she moves through, and we've both seen things in that house that remind us of our own families and the glittering dysfunctions they orbit. Edith Finch creates conversations. It makes you remember things you maybe haven't thought about in a long time. It did for us, anyway.

And it's all down to those locked doors, each one holding back a singular, intoxicating experience of the world. Each one, in its unyeildingness, offering the sense of a museum, or a zoo, or a prison. All of these interpretations are valid, I suspect. Every family, suggests Edith Finch, is a collection of different worlds. And as important as the things that bring siblings together are the things that allow them to stay separate, to retain their own distinct, if interlinked, identities. In the end, what remains of the Finches is the latest Finch, along with the stories of all the previous Finches - there to provide a template for living that can easily be ignored.