When being a fan turns into a career

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but it's also the quickest way to a copyright strike if you're not careful. It's only natural that when someone's inspired by a creative work that they'll want to create something similar. As such, fan art honouring video games has become an entertaining hobby, a great way for aspiring artists to get their name out, and fine social tool to meet likeminded folks. What it isn't, however, is a smart way to make money. Video game publishers are often shrewd kingpins of copyright law and while Nintendo may be charmed by the millions of Zelda artworks its inspired, the minute you start asking for money for that stuff it's a different story.

This was the case with Michael Patch, a huge Zelda fan who spent years collaborating with other passionate players on a Zelda animated series on YouTube. Nintendo didn't seem to mind until he asked for money to fund a follow-up episode. Then Nintendo minded quite a lot and the project was shut down.

However, every once in a while an artist or fan community produces something of such high quality that those holding the copyright for its source material will cautiously lean forward and whisper "you did good, kid. You did good" before allowing their esteemed fans the rights to make money off their properties.

The developer

This was the case for Ryan HoltKamp, whose The 7th Guest spin-off game The 13th Doll not only has the blessing of series creator Trilobyte to exist, but it even has a licensing deal in place where it can sell the game for money. HoltKamp's pet project has been so successful that it shot past its $40k Kickstarter goal in only a couple of weeks. That's more than Trilobyte's official sequel raised when it went the Kickstarter route after its first failed crowdfunding campaign.

It all began in 2004 after HoltKamp had finished college and decided to make a standalone title inspired by his favourite game The 7th Guest. Around that time Trilobyte was developing an actual 7th Guest sequel, but the project was canned, so HoltKamp decided he would make his game exist in the series that inspired it.

He wasn't naive about it though, as he knew that he wouldn't be able to profit off it this way. But by tying his pet project to The 7th Guest, he was able to use it as a recruitment tool to gain volunteers to help him realise his vision. "I'd been a student and was really excited about making video games, but no one else was with me," he tells me over Skype. "It was largely because this game has a fanbase and I could tap into that and find fans like me who were willing to make the game and capable."

HoltKamp's plan was simple: Step One: Make an unofficial The 7th Guest game to prove his talents. Step Two: Get a job in the video game industry where he could lead development on his own games. Of course, step one was a legal minefield and HoltKamp knew he could be shutdown if Trilobyte didn't approve.

"In 2004 we were really afraid of that, because we followed the King's Quest fan game and it was cancelled. They got a cease and desist, so we lived in constant fear of that," HoltKamp says before noting that he and his crew even had a backup plan to change all the names to avoid getting shut down.

Thankfully his worries were unfounded. Trilobyte really liked what it had seen on The 13th Doll. In fact, it liked it so much that around 2007 it was willing to let HoltKamp and his crew use the The 7th Guest license, but with some pretty strict limitations: Notably that the devs couldn't profit from it in any way, nor could they use actor Robert Hirschboeck.

"It was absolute relief, because we were terrified that we'd just be shut down," HoltKamp says of this initial offering. And yet, even with the series' creators' blessing, enthusiasm for the project diminished over time. HoltKamp had a second child, other volunteer devs found jobs and careers and The 13th Doll was left in shambles for seven years.

It wasn't until earlier this year that he decided to resurrect it. "I really missed working on The 13th Doll and it really meant something. It was really special," he tells me. "We had made really good progress. We were over halfway done with this game and just needed to finish it."

After finding a few people to help him pick up on where The 13th Doll left off, the fans at Attic Door Productions began posting their progress on Facebook. Shortly thereafter, Trilobyte got in touch with an even more alluring deal than before: Attic Door could sell The 13th Doll for profit, use Robert Hirschboeck (if they could afford him) and even raise money for their game via Kickstarter.

"It was just utter disbelief. It's amazing. We were just in shock," HoltKamp says. "It's a dream come true. It's so high in the sky. I couldn't imagine something like this happening."

One of the stipulations behind Attic Door's deal with Trilobyte is that the fan company needed to raise its own funding. Nobody expected it to raise more than The 7th Guest 3, something that bewilders HoltKamp as much as anyone. "I hope it's just because our passion for it shows through," he ponders.

Ultimately, this is a mutually beneficial deal for Trilobyte and Attic Door. The fans get to make a licensed commercial game in the property they most admire, while the original series creators get free marketing as they try to resurrect the storied series two decades after the fact. It's a win-win.

The musician

Raheem Jarbo, a middle school teacher turned nerdcore rapper best known by his stage name Mega Ran, also found himself in the unlikely position of an officially licensed fan. Best known for his self-titled 2007 album Mega Ran, Jarbo sampled tunes from one of his favourite video game soundtracks, Capcom's iconic classic Mega Man.

"I put the album out before I got any permission or okay," he tells me. "It was more of the hip-hop train of thought where you do things not necessarily expecting them to be the thing that defines you for your entire career. But you do something just hoping to make a mark creatively and to have fun. You kind of hope to ask for forgiveness later rather than permission."

Jarbo released Mega Ran as a free download, but he still lived in fear of a cease and desist. "I was very worried," he says. "My friend who's a lawyer told me that at the least I should be worried about a cease and desist or it just being taken down from my website. And I was ready for that, but it didn't happen."

Instead, Capcom reached our to Jarbo to tell him that they liked his personal spin on the company's flagship franchise and wanted to interview him for the Capcom Unity blog.

This was a big win for Jarbo, who could now rest easy that his creative output would remain accessible to the masses. But it still wasn't technically licensed. That came later later when a friend of his in the film industry wanted to use one of his Mega Ran songs in the end credits of the movie Second Skin. When he asked if Jarbo owned the rights to the music, the rapper told him that he didn't. "So he's like 'well you've got to go get a license from Capcom.' And I'm like 'I don't know anything about that. That sounds really scary and legal," Jarbo recalls.

Thankfully, this smooth-talking friend somehow made it happen. "The next day I get an email from Capcom saying 'you are now officially licensed to create music using Capcom samples,'" he says. "If it was me it would have probably failed instantly."

The Mega Ran album went on to launch Jarbo's career in music. He even released a sequel album entitled Mega Ran 9 to coincide with the release of Mega Man 9. Yet, despite this, Jarbo doesn't go around seeking licensed deals. "People may look at me as Capcom's rapper and not want to license me," he says. "I guess I wouldn't necessarily like to be licensed. I just think it's a cool story to be able to tell people 'I was the first rapper to be licensed by Capcom.'"

While Jarbo was fortunate in his musical endeavours, he's known others who have used copyrighted samples with less fortunate results. "I've learned that it's always better to contact the companies. Any time you're using anybody else's material you should be aware and ready for the possibility that they could sue you," he says.

"But you said you were glad that you didn't check," I tell him. "So which is it?"

"I don't think they should, honestly," he laughs. "I say just put it out on the internet - don't sell it, don't try to make money from it - but I would say put it out. Make sure it's really good though, so when they do hear it, they're like 'oh wow. This is really cool!"

"That's just my opinion. This is not legal advice in any way."

These days Jarbo makes a full-time living as a musician, though it's not all about video games. He released an autobiographical album called Language Arts in 2012 (he was a language arts teacher, you see), and his upcoming album, Random, features no video game covers, though it will include a lot of original chiptune compositions.

"It takes a lot more work to come up with a catchy song that people are going to like that doesn't involve a game that sold 5 million copies. So I definitely think I put more time into original stuff," he says. "The impression might be that I just create video game stuff because people like it, but that's not true. I create it because I like it."

The professional fan

Reid Young, co-founder of Fangamer, had his life forever changed when he played Earthbound, though he didn't know it at the time. In his teen years he started the Earthbound fansite Starmen.net, an act that inadvertently led to him meeting his life-long friends, co-workers, and even wife.

"Earthbound provided an excuse for us to get together and hang out and work on projects," he tells me over Skype.

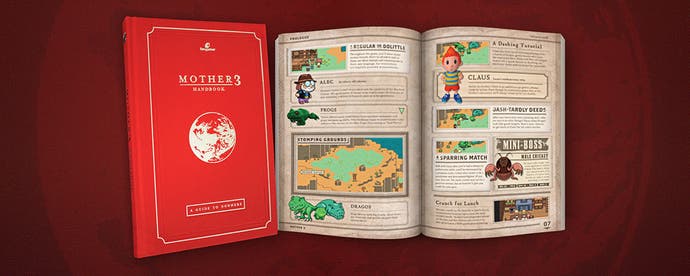

One of these projects was the Mother 3 handbook, a guide to Shigesato Itoi's Japan-only sequel to Earthbound. Young and his cohorts at Starmen.net had previously taken it upon themselves to release an English language patch that finally allowed the western world to play Mother 3. But, as with Earthbound, and it almost demands a player guide - something the original Earthbound was accompanied by.

"We wanted to give people playing the game in English for the first time the same experience that we had playing Earthbound as kids," Young tells me. It was upon researching this that Young came upon a remarkable discovery: creating a game guide doesn't infringe upon any copyright laws. "We found that a small number of company - mostly just one - had kind of cornered the market and had been given exclusivity in terms of creating guides. And after a bit more research we found that it's not that guides are illegal, it's just that nobody's doing them.

This handbook to an already niche game ended up being unexpectedly popular - so much so that it launched Young's career running Fangamer, an online store selling both licensed and unlicensed video game paraphernalia. This may sound fishy, but Young and company have a strict policy about never using trademarked material.

"We never take something directly from a game. We always try to evoke the spirit of that thing," Young explains. For example, one of Fangamer's earliest Earthbound T-shirts used visuals from the PSI Rockin attack. "One of our first shirts was a design that has all these crazy shapes springing from a small character's hand and it fills up the entire side of the shirt. It's not directly from the game, but fans of the game will almost instantly recognise it. That's what we've always gone for."

"We would never use copyrighted names, titles, logos, whatever. So if we make a shirt inspired by Mega Man, for example, we would never say 'Mega Man' in the description or the title because it isn't [ours]."

"We wouldn't want to profit off of that name," he adds. "We want people to come here and find it because they're fans of video games and they just happen to come here and find Mega Man. We don't want to come up at the top of a search for Mega Man t-shirts, as that's kind of slimy."

In all this time Fangamer has never once received a cease & desist notice, though it was slapped with a takedown order once due to a weird technicality where a user review on the site mentioned a franchise a shirt was evoking. But even this snafu was swiftly resolved by implementing a new comments policy.

Occasionally Fangamer sells licensed material, too. After producing the Kickstarter backer rewards for the documentary Mojang: The Story of Minecraft, the company started getting more offers from small developers to create official merchandise for them. Now you can buy licensed t-shirts for Retro City Rampage and Octodad from this once rogue studio.

Young isn't worried about selling out though. "We've always had an internal code: we try not to do merchandise for games that have their own merchandise," he tell me.

"Originally our motto was 'professional fans'," Young says. "That's kind of what we pursued. Sometimes fans become the informal marketing team, kind of like what you saw with Shenmue. They took on the mantle of marketing the Kickstarter for that game. So with games like Earthbound, where Nintendo had seemingly abandoned it, we kind of took that on as our project to keep it alive, to keep people talking about it, to get new people interested in it."

And interested they have been! Young and his colleagues launched a Kickstarter last year for an Earthbound handbook that raised $230k, well over its $100k goal. That's pretty impressive given that the original game already launched with a player's guide back in 1994.

"Obviously Earthbound already has a players guide, but there is soooo much [left to discover]," Young says. "The game is an absolute treasure trove of things we've discovered since it came out. Literally a couple of weeks ago we had a convention and someone discovered something in the game that we'd never seen before."

The Kickstarter also comes with a zine of fan art. "We've always had really high standards in terms of what we'd accept," Young says. "One thing we definitely don't accept or endorse is people just straight up copying the official art. We're pushing people to come up with their own original takes."

So how have Itoi and Nintendo, a company infamous for its finicky streaming policies on YouTube, responded to this? For the most part, they haven't. But the few interactions Fangamer has had with its heroes have always been positive.

Back in 2007, when Young and his crew were working on the Mother 3 fan translation, Nintendo invited him to the company's US campus in Redmond, Washington to interview him for Nintendo Power. "[It] was definitely the height of our legitimacy and fame as fans back then," Young recalls.

While the invite and article were a great honour, Young was still nervous about visiting the NOA campus. What if the mysterious Kyoto-based company looked down upon him? It made the games, after all. He just gushed about them.

"We sat down in the cafe and were sitting next to Nintendo employees. We told them who we were and what we were up to and they were like, 'oh, so you guys are doing the Mother 3 fan translation?'" Young reflects. "It was kind of like going into the lion's den and I didn't quite know how to respond, and then they were like 'oh, don't worry about it. We're really excited about it. We can't wait to play it!' And that just knocked me flat. I didn't know how to respond to that because it was so unexpected!"

"The idea of them being excited about a fan translation was just so out of nowhere to me," Young continues. "That was the first time I started to open my eyes about what Nintendo is as opposed to what I saw it as growing up. I always imagined it as this monolithic company that knew exactly what it was doing and had clear responses to everything. And now that I run a business and just have experience being an adult, I realise that it's a massive company. And just because some people are excited by something it doesn't mean that the company is going to endorse it. There's all kinds of nuances and shades of grey."

Indeed this grey area explains why Nintendo, as an official entity, has neither brought down the hammer on Fangamer, nor endorsed it. The same goes for Itoi, who only conversed with the Fangamer folks once for a charity drive.

Young reached out to Itoi for the first Earthbound Bash in 2013, a charity event in which the the Fangamer staff would play through the game live, accepting challenges from those making pledges over the livestream. One of the charities was helping a young man with cancer who gave his pristine copy of Earthbound to his friend when they were children. The friend collaborated with the Fangamer staff to get Itoi to sign the cartridge so it could be auctioned off to help fund the original owner's treatment. The cartridge sold for $14k.

"This was the first thing, to our knowledge, that he ever signed with his english signature," Young says. "It was certainly the first time something with his english signature had been auctioned off."

Beyond that, Itoi has shied away from commenting on Fangamer and Starmen.net, which Young believes is due to his close relationship with the late Nintendo president Satoru Iwata. "He and Iwata were best friends basically, and the've worked together on a variety of things since Earthbound came out. So he's very careful not to do anything that could damage that relationship," Young says. "He acknowledges that he knows about us and seems to enjoy and appreciate what we've done and the things that we do, but he's also very careful not to say 'hey, this is a-okay!'"

The take away

It doesn't always work out so swimmingly though. Patch kept making Zelda art thinking it wasn't a problem, but the fan backlash to his Kickstarter for a Zelda animated series was so strong that it soured his feelings on the project before Nintendo was even able to issue a cease & desist.

"I only wanted to do this as long as almost all of the fans were supportive," he says in an email to Eurogamer. "I was trying to do what I had seen other people do (raise money for a project using IP's they didn't own) and mine was getting a lot of flack."

"Bottom line (from what I have gathered) seems to be that you can fund raise cover songs and music videos, that use Nintendo's IP's, but you can't fund raise a film that uses Nintendo's IP's (not including parody)," Patch realised too late.

Fan art is certainly a sticky legal conundrum and it's never clear how a company is going to take it. Some find it endearing, others try to fight it so it doesn't colour one's feelings towards an IP from an untrained eye mistaking it for the real deal, and many fall somewhere in the middle.

Distributing fan art is risky and can result in countless hours wasted on projects that later get pulled. But sometimes rights holders and video game creators find this sort of thing charming enough that it gets their blessing. I reckon most developers are flattered to hear folks enjoy their work. Hearing it launched someone's career is probably even better. Perhaps we're entering a world where that adoration is more important than royalties.