When idiot elves and sexy clerics become a class act

How D&D's nuanced approach to character pays dividends.

I am a fearful man at heart and in the flesh - one who whimpers and nibbles at the blankets when I hear creaking after dark, one who whistles on my way past the graveyard.

Gaming should allow me a sweet escape, but check this out: I play Spelunky, where I inch my way, terrified, through an endless gauntlet of traps and horrors. I play FTL, where I inch my way, terrified, through a galaxy filled with pirates and spinning asteroids and nasty skirmishes that set my door-opening equipment on fire. I play XCOM, where I inch my way, terrified, though a shattered local Waterstones, civilians glued to the floor with green gunk and thin men hiding in the darkness ready to shred my expensive mechs. I have mechs, but all I can think about is how much they're going to cost me to replace when they're gone. In games, as in life, I'm so preoccupied with trying not to lose that I forget that I might be able to win. I'm fascinated by failure, apparently. I certainly want to be in its orbit at all times.

Enough therapy. My point, I think, is that when I play video games, I generally forget that I don't have to roleplay as myself. All of which made it a lovely surprise last night when we gathered in the office for my first ever Dungeons & Dragons session (there were a lot of first-timers around me, too) and I suddenly discovered, hey, I can be somebody else here - and that might be hilarious.

It was hilarious, but I'll get to that in a bit. Oli's already written about D&D and how it differs, in dynamic, exciting ways, from the video games that have been inspired by it. He's covered a fascinating schism that saw the free-wheeling Basic Edition separate itself both philosophically and mechanically from the prescribed, labyrinthine, stiflingly comprehensive rules of the Advanced Edition. Today, a blinking neophyte, I just want to talk about characters: about how D&D allows for an astonishing range of options when it comes to who you can meaningfully be that I've never encountered in a video game before. As Oli wrote, video games allow for role-playing - but I often forget about the things I'm merely allowed to do. D&D demands role-playing. There is no escape. There is no escape from escapism.

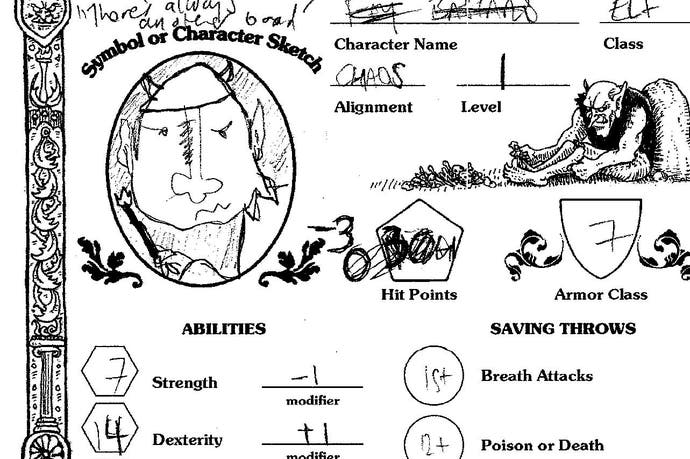

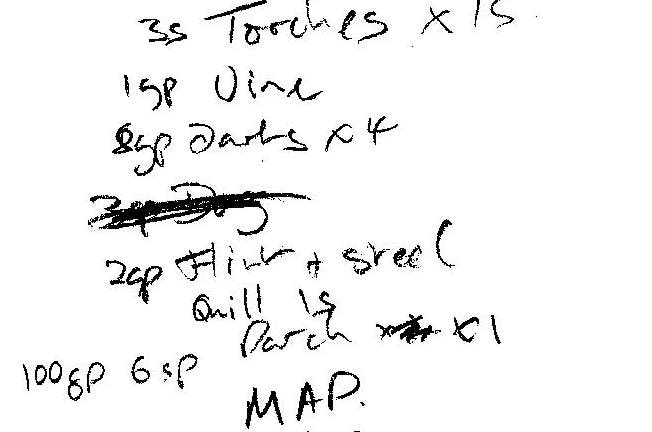

So who was I last night? On paper, I was an elf, a decision I made because, looking at the list with the eyes of a video game RPG fan, I saw a natural hedging class: melee and ranged but also a little magic. I'd have to deal with NPC racists who don't like elves, but maybe we wouldn't meet any. Maybe I'd be an elf who wears a massive hat so that nobody can see my elfen-- Wait! It had already begun.

The elf racism thing is a neat springboard. Lots of video games have this sort of background texture, of course, but it's often little more than that. Take the wizard in Diablo 3 - wizards in Sanctuary are meant to be a kind of upstart mage, young and cocky and perhaps a little ragged when it comes to the implementation of the weird arts. In truth, though, for most people, these are all just nice ideas to read about in the tooltips. When I play a wizard, the combat focus and the sweetshop skills that make up Diablo 3 wipe all that deeper stuff away - because it isn't truly the deeper stuff of the actual game. Laser beams trump lore in Diablo, especially when you can fire them in all directions as you race through a room packed with skeleton archers. And you're always racing through a room packed with skeleton archers, or fallen demons, or other sorts of people who don't care that you're an upstart mage who's - hey! - just freestylin' out here. They couldn't react meaningfully to that information even if they could care about it.

So I already knew I was an elf who was going to wear a big heritage-hiding hat. This suggested someone a bit sneaky, a bit snivelling, a bit underhand and ashamed. No big reach for me, perhaps, but as the game began, as I rolled my character stats and started to interact with the other members of my party, as I started to engage with the quest for loot, other details came to light - and they really changed the game and the way it unfolded for me.

I rolled very low charisma. Shockingly low. Angela and Friends low. I felt hazy regarding what charisma actually translated to in terms of mechanics, but nobody else was: My elf instantly became the guy who nobody wanted to be around. When we went to a pub to learn a little more local info about the clifftop dungeon we were going to be raiding, it was decided that I had better stay outside and look after Bertie Purchese's donkey and the canoe Martin Robinson had decided to bring along, in case I put my foot in it.

Inevitably, I put my foot in it in anyway.

While the gang was inside making friends, I started to get bored and look through the stuff I had brought with me. I had a grappling hook! Hey, wouldn't a feeble sort of elf with three hit points to his name (if I went inside and a pint glass fell on my foot, it would probably kill my whole family), prefer to hide on the roof of a pub in case any elf racists were in the area?

He would, and I could. This is the freedom of Basic D&D, of course. May I hide on the roof? Why not try? What's my dexterity? Where are the dice?

While I was on the roof, some elf racists appeared. They kicked the boat to pieces, and they freed the donkey, who then ran away. That was pretty entertaining, particularly since Martin had named the boat after his cleric's beloved son. It was even more entertaining, though, when I decided I was going to lie about this whole escapade to everyone else. I wasn't going to lie out of fear, mind: I was going to lie because my character had just snapped sharply into focus. I was a feeble but deeply blasé elf. Life was full of dangers that I simply didn't register, and I saw no value in telling the truth either. Why should I? I had a giant hat and a grappling hook, and I didn't know I had no charisma. I thought I was the most charismatic guy going - it tallied with my freewheeling who-gives? attitude to life. The hunt for buried treasure was about to get chaotic.

And chaos was what I consistently delivered. Hours later in a battle against those very same elf racists in the middle of a forest, I decided to ditch a straightforward attack with my hammer in favour of a more interesting strategy. I would whistle, very loudly, in the hope that Bertie's runaway donkey might be grazing nearby and would come bowling through the undergrowth to knock our assailants off their feet. (It wasn't, and it didn't.) Later, in the first passageway of the dungeon we were intent on sacking, I initiated a fight with a sand monster by challenging it to a game of backgammon rather than backing away to safety, and then I flipped the board in its face in the hope that the board was heavy and would give me the element of surprise. (It wasn't, and it didn't.) The defining moment of the whole game, though, came when I decided to double-cross my entire party and throw in with an evil mirror-world version of myself so we could keep all the loot. This was a dynamic plot-twist born of the empty, dextrous mind of the breezy, self-serving moron I was playing as.

It could have ended the game. It elevated it. For the rest of the adventure, we were a party that never fully trusted one another. Tom Bramwell's knight got his head blown off as a direct result of that decision, and as an indirect result I ended up back in town with a wand that changed people into animals. I turned the barmaid into a dog (I had gotten Dan Pearson's own dog killed and I wanted to make amends), and then, when everyone freaked and scarpered and the city watch appeared, I defused that situation by turning one of them into a bear and clearing the place out completely in the panic that followed.

I've never rolled a blasé elf in a game before. I've never been given a mechanic that hinged on being blasé. Being blasé in the face of skeletons and sand monsters doesn't actually sound very promising, in fact, but in this game it was perhaps the most important decision I made the whole evening. It introduced just enough unpredictability to proceedings - and the other players adapted brilliantly.

I almost want to say that the rest of the cast adapted brilliantly: Dan, the torture-happy, pedantic dwarf, embittered by the moment he had to cross the single word 'dog' off of his inventory; Martin, the dewy-eyed sex-pest cleric who brought a canoe to a knife fight; Bertie, the warrior fool who just wanted to be a writer; and Tom, first a heroic and noble knight who got his head blown off, and second a heroic and noble knight's brother who wanted vengeance. He got it, too, but not before I turned him into a heroic and noble horse - a horse that then kicked me to death.

What an astonishing, unlikely adventure we had - five wheezing, addled vagabonds and chancers without 20 hit points to share between us. Martin got us out of one nasty fight by trying to throw Dan's dog at the baddies (amazingly, that's not what killed it), while Dan won the entire game by neglecting to tell everyone else about a trap he had spotted. Bertie kept getting clubbed unconscious, Tom kept dropping his sword, and Martin again, misreading the rules, didn't bring a weapon along with him because he thought he wasn't allowed one. So many brilliant, idiotic elements made the game what it was, and they all stemmed from our unusually distinct and precise classes: sexy cleric, unlucky knight, Dan. Most games really don't cast the net wide enough, do they?

If this all sounds a bit like therapy again, it probably is. In therapy, you're ideally led from one revelation to the next without really seeing the guiding hand. In D&D, a good dungeon master will give shape to the story by feeding the individual characters promising options in ways they'd never spot at the time. It was only headed home that I realised I'd possibly gotten that wand because the game was moving rather slowly at the time, and because I was also uniquely useless in a fight. Hey, maybe that boat got kicked apart because Martin was never really going to need it, and it gave everyone an opportunity to suspect me of something - and for me to be worthy of their suspicion?

Our dungeon master has now told me otherwise, but it was still quite a performance, and he did a lot just to keep us focused and headed in broadly the right direction - and that's before you get to all the surprises he had planned. Dungeon masters as creative, as subtle, as reactive, and crucially as self-effacing as this are probably beyond the scope of video games for a good while yet, no matter how brilliant the weather effects in modern games become, no matter how many on-screen enemies they can chuck in at any one moment. In the meantime, though, a more imaginative approach to character classes - and a more imaginative approach to bringing the peculiar nuances of a character class into the game in ways that make a difference - wouldn't go amiss. Just listen to the elf on the roof - that guy knows what he's talking about.

Thanks to Andrew Walter for being a brilliant DM. You can download a free version of Labyrinth Lord, the game we played, and buy print and e-book copies, from Goblinoid Games.