The Big GAME Shutdown: An Insider's Account

"In the course of those couple of hours, most of the people I've ever worked with were gone."

"Once the boxes had gone, he [the administrator] did a walk around the store. He was asking us what we planned on doing next. If I'm honest, I was a bit short with him. He was saying, 'What are you going to do now - have you got any plans?' And I was like, 'I've just lost my job. I've been doing this job for two-thirds of my working life, if not more than that, working in a game shop. And suddenly I haven't got that option. So no, I don't know what I'm going to do now. First things first, I'm going to make sure I get the money that I'm owed. But I don't know, I don't know what I'm going to do.'

David Jennings was assistant manager of Gamestation Congleton, one of 227 GAME and Gamestation stores closed by administrators. He was also was one of 2104 staff to be let go by the end of the most devastating week in GAME Group's history. "My first reaction was complete and utter shock. I was a bit devastated," he remembers. "It's incredibly brutal; I know that's what administrators do, but going from the day before, thinking well we're supposed to be safe until the end of the week, to suddenly, within a couple of hours on Monday morning, being told that I wouldn't have a job any more..." This is David's story, an account from the front line of GAME's battle for survival - the shop floor.

The day he lost his job

Roughly nine years earlier, David Jennings started work part-time at GAME in Crewe, where he lived. Working there meant combining a wage with a hobby he loved, and it meant getting out of McDonald's. "The amount of people I met," he tells me, "who said 'I'd love to work in a game shop!' - it made me feel really proud and like I was lucky to be in this position."

Jennings joined Gamestation - then a rival video game seller - four months later, in April 2004. He wanted more hours. He rose to assistant manager within seven months and stayed at the store for more than three years. He left in August 2007 (two or three months after GAME acquired Gamestation) to go back to University. But months later, after a brief stint selling phones, he was back again - this time as a Christmas temp at GAME. And there he stayed for four years, before accepting an assistant manager role at Gamestation Congleton. He worked there until a month ago.

Jennings had a day off when a friend phoned from another store and said, "I think your store's gone, Dave." Jennings then spotted a friend on Facebook bidding farewell to the Altrincham Gamestation store, but had been told internally that voluntary administration wouldn't happen until the weekend. It was Monday, 26th March. Then the phone rang again. "I had a phone call from my store manager saying, 'We have entered administration.'"

"It wasn't until that memo came down that obviously we realised maybe there is some truth among the online reporting."

David Jennings, former assistant manager, Gamestation

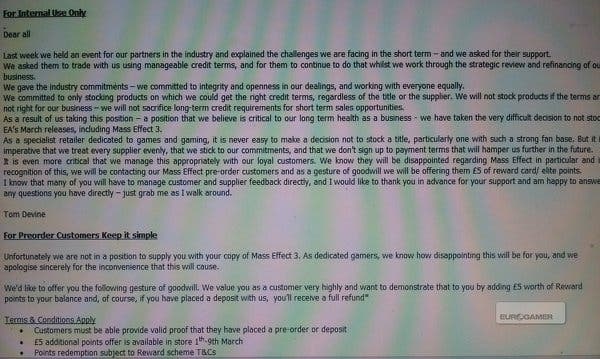

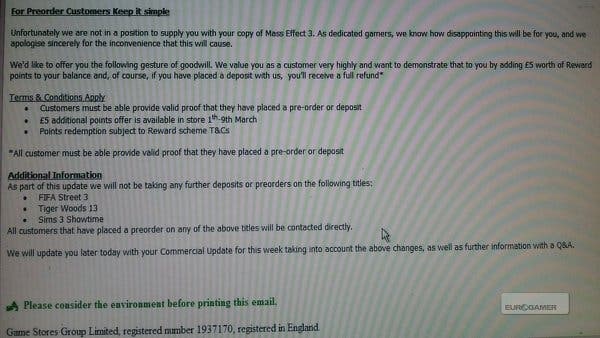

The Mass Effect 3 memo

The first time David Jennings knew things were really bad was a month earlier, on Wednesday, 29th February. Head office had sent an early morning memo informing staff that GAME wouldn't be selling Mass Effect 3. "I read it first in store and printed off the initial email and showed it to all the staff," Jennings says, "and it was later on that morning it leaked and spread like wildfire.

"That was sort of the first official line that there were problems. Up until that point, although we'd seen less stock and we'd read different things online, there'd been no word from the company. It wasn't until that memo came down that obviously we realised maybe there is some truth among the online reporting."

David Jennings was worried, "and I could tell the staff were." "It was incredibly uncomfortable, because gamers pick stuff up incredibly quickly online and they were coming straight into store and going, 'What's this about Mass Effect?' And we were refunding deposits and things. And the more of them we did, and the more people who came in going, 'What's going on, are GAME going? Is GAME closing?'

"We were told to just basically say there was a supplier issue," Jennings recalls, "and that sadly we wouldn't be stocking it. We had regulars staring at us going, 'Come on! There's more to this than that!' But that's all I could say. That's all I knew!"

Jennings kidded himself that "maybe this is EA just being a bit bullish", and recalled a FIFA Street 3 dispute from a couple of years ago. "But in the back of my head I was like, is this the start of a real downward spiral?"

Inklings

The first time Jennings suspected things weren't right at GAME was during the busy Christmas period last year. Head office had warned that the company may not turn a profit - something that struck Jennings as "a bit odd". Then, Christmas stock levels were lower than usual, something Jennings hoped constituted GAME being "a bit more sensible this year". But as the New Year arrived, nothing changed, "and we weren't really getting anything". Jennings couldn't meet demand for Kinect, he recalls, and even though his store had "a lot" of vacancies, "we weren't allowed to take anybody on".

This internal doubt was underlined by online reports that started appearing after Christmas. (It seems a long time ago that Eurogamer pinned GAME and was reassured about the road ahead.) First came GAME's gloomy financials, then doubt was cast on the shop-chain's ability to buy and stock new games. "It was at that point where we all started looking at each other and going, 'This isn't great!'" says Jennings, who recalls looking briefly at other jobs, "because I had this funny feeling things were going to take a very big turn for the worst."

After the Mass Effect 3 memo

In a bizarre way, the Mass Effect 3 memo showed Jennings that GAME HQ had been right to withhold information internally, despite the bitterness this bred among staff. "[It] kind of proved they couldn't trust everybody in the company to keep it amongst themselves," he reasons. "That's probably why they weren't more open, which is a shame, because we deserved to know more than we did over the course of the first few months this year. We were really kept in the dark."

The 'memo after the Mass Effect 3 memo' arrived "a few weeks later", and contained a list of games that GAME wouldn't be stocking. "It was then that everybody was like, 'It looks like this is a problem.' And then it started to get really frustrating, because we'd just not been told," Jennings stresses. "These memos kept coming down saying we're not going to be stocking this new release, we're not going to be stocking that new release - but no answers."

This limbo was reflected on a store level, where there was less to do. Jennings and his staff spent more and more time in the store's back office surfing the internet for updates. "We did have fewer tasks - there were price changes and things, but the deliveries were getting smaller," Jennings recalls. "I heard of stores that literally downed tools and sold games and that was it. They didn't clean, they didn't do action plans, they just did the basics, which is fair enough. We were still doing little things like plans for the day, when really did we have to? I guess we didn't, because nobody was really checking at that point."

Customers were irritated but generally well behaved, and Jennings says "we managed to talk our way out of any [situations] that seemed to be escalating". Nevertheless, people wanted to know if and when a game would be in Jennings' store - a simple question he couldn't answer.

"I remember one guy," Jennings recalls, "luckily he was a regular: he picked up a copy of SSX and said 'I'll buy that' using his Trade-in Card. And we said 'I'm very sorry but we've sold out'. And he said 'Oh right. OK, I'll have Kingdoms of Amalur instead'. 'Sorry, we haven't got any of those either.' And he'd be like, 'OK, well in that case I'll pre-order this game.' And we were like, 'I can't take any more pre-orders on that.'

"I've worked with a lot of people over the years, I've covered in a lot of different stores, and in the course of those couple of hours, most of the people I've ever worked with were gone."

David Jennings

"Luckily he saw the funny side. Even though he had £60-£70 on his Trade-in Card, he knew us well enough not to get angry with us. He really tilted his head back and went, 'Ho ho ho, well what can I buy? Do I have to buy a pre-owned game, then?' Because it did get to that point where we nearly only stocked pre-owned games because we had nothing in new."

Not only did Jennings not know the answers himself, he also had to toe the company line - even when it veered dangerously towards deception. He still had to advertise console bundles even though his store didn't have the games to go with them, and "there were a lot of empty dummy cases advertising games we weren't sure we were going to get". He explains that "we were always told we couldn't write on boxes that were out on the shop floor that we'd sold out of any particular item".

Some mornings he felt like rebelling and taking down all of the game boxes that were out of stock. "But I guess, I don't know - maybe it's just in my manner. We didn't know what was going to happen," he verbally shrugs. "I hoped that if I carried on how I was going, our store would survive. Or if our store didn't survive, maybe I could go into another store. I didn't want to do anything silly, if you know what I mean, and get myself into trouble."

"I like to think that I acted professionally," he says, but adds, "Yeah, maybe it wouldn't have hurt to be a little more rebellious."

After the closure

"I've worked with a lot of people over the years, I've covered in a lot of different stores, and in the course of those couple of hours, most of the people I've ever worked with were gone," Jennings says. "They were unemployed.

"We didn't get any redundancy from the company at all. We were paid until the Friday."

On Monday, "there were tears". One of the two sales assistants Jennings worked with had paid for a holiday to Vegas she now wouldn't be able to afford. There was also a phone call to the police.

"[The staff] had to call the police out because they had people who were smacking on the doors and things, wanting to bring stuff back, or wanted to spend their cards," Jennings reveals. "So they were sort of kicking on the doors and things. The people who were in the store at the time had just found out they'd lost their jobs, and they were obviously already upset. They had people banging, there was nothing they could do other than just close the shutter, basically."

Jennings, who was off work, spent the day online absorbing what was going on. He talked to friends and filled his family in on what was going on. "Eventually I just went out for the afternoon with a couple of my friends, just to have a rant basically, because I didn't think it was fair. I wasn't happy. It was just done in such a brutal way."

"Why weren't we told this was going to be this bad?" he asks. "HMV have been advertising that they've been struggling for years, and yet they're still going. We have a bad year and this happens. How did we not just learn from this bad year and move on?"

He had until Friday for his store to be packed away, and sacrificed his other days off so he could join the others on Tuesday and "get the job done". "We just did it, I guess. We were all obviously upset, but we used humour to get us through - the actual week itself was OK. The saddest point for me was the second-to-last day, when I was starting on the bigger things like the tills. That's when it really sank in: 'Wow, this is it.'

But it was Friday "when I had any kind of tears; when the delivery driver came to pick up, basically, the store in boxed form - hundreds of boxes." It was looking at these boxes that Jennings had the grim realisation of "knowing that I'll probably never sell a game again".

"Yeah, it was incredibly sad to lock the store for the final time. It's not like I could just go and apply for another games job, because GAME and Gamestation won't be taking on for some time."

The sword was double-edged even for those 333 GAME and Gamestation stores that survived the cull. For it was those people who bore the brunt of shoppers whose Gift Cards or Elite Cards or Reward Cards couldn't be accepted. "Even though they were open," Jennings says, "they were getting the angry and aggressive customers demanding refunds, demanding to spend their money."

After GAME

David Jennings' Gamestation store didn't have a farewell party and he didn't hear of many regionally. He also didn't hear of any opportunistic last-day stealing. The three people Jennings used to work with all have new jobs, unlike him. He also knows of other former GAME employees that are back in work. But none work in the video games industry. That they may never return - and we lose the next generation of journalists and developers and so on - is a worry that was raised in my What Would Happen if GAME Died? investigation earlier this year.

What's more, Congleton now has no dedicated video games store. You can go to a small Morrisons for a meagre two-bay offering, or venture to the outskirts of town to a Blockbuster store Jennings doesn't imagine offers much. Even Jennings found himself buying Ridge Racer Unbounded from - "shocking, I know!" - Morrisons.

As for Jennings, he's signed on. He's dedicating his time to a career he's been aspiring to for some time: video games journalism. His efforts are being poured into his blog, GamePad, and Blast Process, a gaming blog he contributes to.

He and 300 other former GAME employees are part of a group on Facebook trying to work out how best to get government redundancy pay - a process that's ongoing.

Reflection

Yet, despite all that's happened, Jennings doesn't begrudge GAME, and he genuinely hopes new owner Baker Acquisitions "can turn things around". He'd like GAME and Gamestation shops to exist for "years to come", and he's "incredibly proud and happy" he worked there - "I know how many people handed in their CVs in the hope that one day they could work in a game shop". "But then, at the same time, I'm really sad," he says. "I worked with some fantastic people over the years. I had a lot of fun."

If the phone rang and GAME offered him a job, would he go back? "I wouldn't go back into a management role," he answers. "These past few weeks have taught me that I need to use this opportunity to go on and do what I really want to do. If I had a phone call and was asked to go back on a part-time basis, nearly full-time, then yes, I probably would."