When VR meets art, something new is created

Dining out.

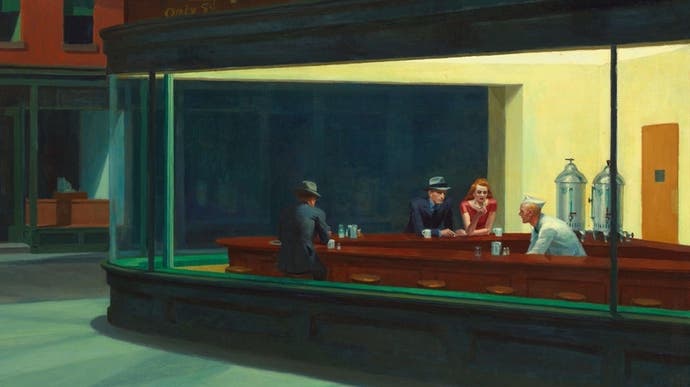

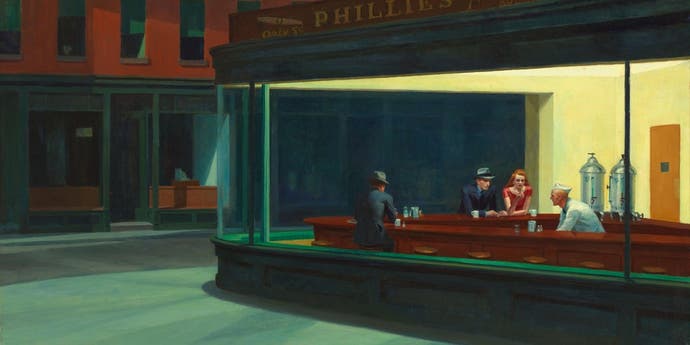

One oppressively hot October day in New York City, the writer Olivia Laing went to the Whitney to see Nighthawks, the famous painting of a diner by Edward Hopper. In her recent book The Lonely City, Laing talks about what it is like to see a very famous painting in real life for the first time.

She speaks of texture. "The bright triangle of the diner's ceiling was cracking," she writes. Not a crack in the ceiling. Not quite. A crack in the paint that has made the painted ceiling. "A long drip of yellow ran between the coffee urns," Laing continues. "The paint was applied very thinly, not quite covering the linen ground, so that the surface was breached by a profusion of barely visible white pinpricks and white linen threads."

This is how it often is when famous paintings are suddenly before us, I suspect. Reproduction makes the image itself famous, but proximity to the real thing gives us back the surface, the painting as an object. It turns us into curators, or maybe crime scene analysts: we look at the canvas and make out the damage, the near-invisible quirks, the interaction of physics and chemistry and time.

Laing is interrupted by a tour guide who explains to her huddled group that there is no door. "She was right," says Laing. "The diner was a place of refuge, absolutely, but there was no visible entrance, no way to get in or out." A door at the back of the room may lead to a kitchen, but "from the street, the room was sealed: an urban aquarium, a glass cell."

The memory of reading all this returned surprisingly sharply when I saw Nighthawks on my Facebook feed last weekend. I saw it afresh for myself, like I was witnessing the original in the flesh, able to gain new insights into the textural reality of the thing. But it was not the original. It was a new original. In a short, jaunty video by VRScout and SoulPancake, I watched an artist named George Peaslee recreate Nighthawks in VR.

I have watched many videos of people working with VR art tools before. Apps like Tilt Brush, which I think is what Peaslee used, and Quill turn out all kinds of incredible things. But watching Nighthawks come together I was struck with the sheer oddness of what I was witnessing. What was compelling was not just the thrill of watching someone with the skill and certainty of Peaslee going about his work - there is something amazing about witnessing an artist in flight because they always seem to know where a line should go; it seems sometimes that they can see the whole thing before it is there and they are simply helping it to emerge for the rest of us. It was not even the cosy recognition of watching a painting I knew slowly reveal itself. It was the thought that this is new. I had never seen someone work quite like this. There was no name for what he seemed to be doing, or rather there were lots of names for parts of it but none of them seemed to be capable of connecting anywhere but right here.

The outside of the buildings, he makes these with blocks, and then he spreads out the brown and green paint as if the controllers he's using are paint-rollers. There is something wonderfully odd about the very normalness of this, if that is possible. He is rolling, recognisably rolling paint, onto a flat surface that takes the paint and holds it - but the flat surface is not there. And the artist himself, in the trickery of the video, is somehow inside his own workspace: we can see his virtual tools, but we can also see him using them. He selects colours from something that looks and acts like an easel, but it is made of light.

And then he grabs the entire diner and moves it around. I am thinking: hmm, group select or whatever it's called. It's the difference between highlighting a letter and highlighting a word on Google Docs, I imagine. But here, it's simultaneously such a physical thing he is doing! He shifts the thing he has made around in the space that he has occupied to make it. To create the outside of the diner he stood outside it. Now he enters it - no door, remember - by moving it around him.

The part that really floors me, though, is the bar stools and the coffee urns - the urns that in Hopper's original are separated by the drip of yellow that Laing spotted. Silva makes them like a craftsman, bent over them, bringing them into being. Then he drops one - a bar stool with a cherry wood top - into the diner where it completely dwarfs its surroundings. He shrinks it down and clones it and populates the scene with the right number of barstools. He has gone from being a carpenter to being a set-dresser, and he's done it all with paint alone. No, he's done it all with virtual paint, with this technologist's dream of paint.

There are no words for this, to tell the truth. It is not painting, and it is not building. It is not even copying, really, because the final work does not feel like a copy of Nighthawks any more than Picasso's Las Meninas feels like a copy of Velazquez's.

For the first time in an age with games - or at least with game technology - I am witnessing something truly unprecedented here. I am witnessing something else.