Who believes what?

What Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo think about games and why it matters.

You might imagine that game developers decide what the future of gaming looks like for themselves, while platform holders like Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo are just there to host their work, but in my experience that's not really true. There's an art to building a successful console dynasty, and it depends on more than just business brawn; you also need a set of core beliefs about what gaming represents that resonates beyond individual systems. Now that the next generation is taking shape, it feels like a good opportunity to take stock of who believes what and why it matters.

I've argued recently that Microsoft's first priority is success as a business and that it hasn't found the right balance with the artistic side of game-making, but it was clear at E3 that there is a firm creative direction running through the Xbox One platform, even if that direction is taking things a little too far too fast.

"You saw a big focus from a lot of teams on immersive, connected worlds," Microsoft Studios boss Phil Spencer noted when he spoke to us. "Creators are definitely thinking about, what does it mean when you can take a tried-and-true genre and think about it in a more connected space?" When he spoke to Kotaku, he went further: "The features and, frankly, the content that is created is expecting an internet connection," he said. "That's where the creators are taking this."

Whether or not game developers were thinking about this before it became useful to Microsoft for them to think about it, it represents a logical focus for the Xbox platform. Microsoft appears to have divided games into two broad categories: 'completed' games, like BioShock Infinite, which are finished when they ship, and 'evolving' games, which are designed to change over time, like Minecraft and World of Tanks. Judging by the Xbox One line-up and Spencer's comments, it is leaning heavily towards the latter, almost to the exclusion of the former.

As with Windows 8, which initially ejected the classic desktop layout in favour of the tablet-loving Metro, this is Microsoft making a bold prediction about the future and then taking steps to get there first. Having experienced great success with Xbox Live and witnessed the rise of free-to-play games outside its walls, it's effectively saying that evolving games will squeeze out everything else, so why wait for that to happen naturally? It's not dissimilar to Sega putting a modem in every Dreamcast in 1998, and as with that decision, Microsoft has discovered that not everyone is ready.

There are lots of differences between Microsoft's approach and that of Sony and Nintendo, but for me the critical reason why Xbox One has ground people's gears so hard is that it lacks any subtlety or patience. It's just another business pivot, with no evidence of durability. When you look at the creative philosophies that underpin Sony and Nintendo's activities, by contrast, you can see why they have helped each company to weather the storm of things like the PSN security breach or Nintendo's chronic game shortages and seen them through weaker generations.

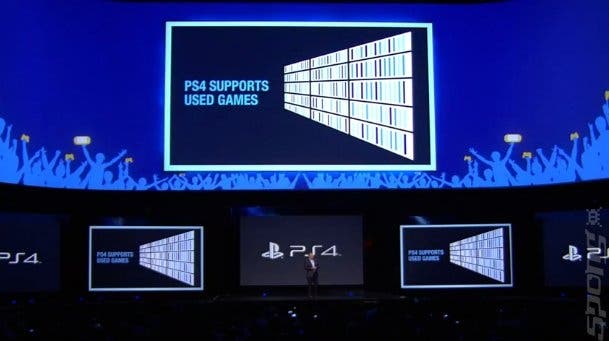

Sony was humbled by developers' struggles with PS3 and the loss of consumer confidence after the network break-in, and my initial reaction to the PS4 was that it was overreacting to that by playing safe to rebuild confidence. "The biggest thing is we didn't want the hardware to be a puzzle that programmers would be needing to solve in order to make quality titles," lead architect Mark Cerny told Gamasutra at GDC. At E3, executives like Jim Ryan and Jack Tretton were queuing up to play down its leadership role. "I think we're not dictating to the consumer or the development community," Tretton told All Things Digital when asked why it wasn't bundling the camera peripheral with the console.

It's all very egalitarian, but it's also rather bland, lacking the strong new flavour developers tasted when they got to grips with PS2 and PS3. But then, perhaps PS4 doesn't need to be as technically exotic as its predecessor, or as overtly prescriptive about how things will look in the future. After all, individual devices are less important these days than the meaning you convey to creators and consumers, and PlayStation's beliefs can speak louder than its stargazing architecture.

Beneath all that matte and gloss, Sony has established an artistic soul. We know it sees games as something more than just entertainment. It's evident in the way it funds creators like Quantic Dream, Media Molecule and Naughty Dog as they explore and experiment, or in the way it sponsors the Victoria & Albert Museum and events like EToo and courts independent developers; it's in the sound of an orchestra tuning up that greets you, to this day, as you switch on the PlayStation 3.

Nintendo has been doing this for a lot longer, of course, and its beliefs sank in long before it experienced difficulties with systems like the N64 and GameCube, largely thanks to one man's lifelong preoccupation with excitement, happiness and surprise.

"What is the role of a game designer?" Shigeru Miyamoto asked rhetorically at E3. "My feeling is that the game designer's role is to create fun and exciting new interactive experiences for people to play." That's it. Over-hyped production values and demands for new IP? These things don't matter to Miyamoto. Better visuals and new games are less important than new ideas. When Miyamoto - and by extension Nintendo, which is built around him - is doing his job right, the sense of delight that comes with those new ideas can be found in even the safest sequel.

Nintendo's statesmanlike endurance and the almost childlike purity of its vision means that it can be pushier than Sony in the way it exports this thinking and still retain people's trust, and we see this all the time. As Reggie Fils-Aime put it during E3, "What matters is how you feel when you play the game." People who make games for Nintendo systems tell us that developer support personnel direct their consultations away from pure design concepts and towards the feelings that games convey, right down to the sound effects that go with individual power-ups.

Sony's latest console is less aggressively futuristic than its last ones - frankly, it might as well have "please don't hate us" stencilled across one of its quadrants - while Nintendo puts us through endless software droughts. So why do we come back to console makers when they screw things up? For me, it's that sense, hard to consciously appreciate, that we all believe the same things. We don't return to PlayStation and Nintendo because we expect them to change. We return to them because we know that they won't.