Why small choices matter when it comes to character creation in RPGs

From tabletop games to Darklands and 80 Days.

Narrative RPGs are arguably all about choices and your power over choices. Choosing a class and a background lays the groundwork for the whole experience of a game and provides a springboard for roleplaying. In the first Mass Effect, for example, you're given two key choices at the beginning of the game that effectively select which version of Commander Shepard you want to inhabit. You decide the personal history and the psychology of Shepard. You decide whether they grew up as the nomadic child of navy officers or on the streets, and whether they matured into a scarred survivor, renowned war hero or a ruthlessly efficient commander.

Each of these choices does have an impact on how characters initially relate to Shepard. Yet for all the backstory, it's hard not to shake the feeling that Shepard might as well have been dropped into the world at the moment you start the game. It's hard not to feel like you're merely guiding Shepard through a world, rather than truly inhabiting the character. The choices are big and can be incredibly satisfying prompts in the hands of a dedicated roleplayer, but the apparent scope of the choices - what was your entire childhood like? - compared to the minimal impact they have on what might be a 100 hour adventure means they can feel a little hollow.

The way in which character and place are crafted in pen-and-paper roleplaying games provides an interesting alternative to this approach.

Taken at face value, tabletop character creation could look like a whole lot of admin, number crunching and box ticking. In practice, though, and with the right people, it's a way of gaining an understanding of the world and having joint creative agency over how your character fits into it. The big choices are made, but so are granular choices about the lives these characters are living. Nicknames, annoying habits and favourite drinks are chosen alongside classes, spells and races as players and the game master create the world between themselves. Even the most broadly sketched tabletop worlds can feel like places that your characters live in, rather than mere backdrops for your misadventures, because of the accumulation of these small choices.

In the 1990s some early RPGs made various, sometimes faltering, attempts to replicate this process. Darklands was one of the most successful failures of the lot, a slightly bizarre party-based RPG about travelling around the Holy Roman Empire in the 15th century. An early attempt at historical low-fantasy, you were just as likely to be scammed by the Hanseatic League as you were to find yourself fighting The Wild Hunt or Satan.

Or, at least, I'm told that's the case because I never really got terribly far beyond Darklands' character creator before being unceremoniously killed by the game's unforgiving systems. This perhaps makes it sound like a waste of time, but character creation in Darklands is less a case of just assigning skill points (although you do this), or choosing a class (although you do this too), than it is of playing through the whole life of your characters up until the start of the game. If you want to create a fighter, you first have to choose each point of progress through their life, from their childhood (urban poverty) to their adolescence (banditry) through to their adult career and later life (joining a mercenary band).

At each stage you assign stat points, but you also have to decide the logic of each small stage of their life. It may primarily be a process of deciding how points are allocated, but it's one that gives those statistics meaning within the context of the lives of your characters.

Moving to the contemporary era, the dazzling alt-Victorian adventure 80 Days suggests how these kinds of choices regarding character might be layered throughout an entire game. In 80 Days the player and Passporteau are both dropped into a world trip with no information other than the knowledge that the valet's new gentleman is something of a gambling man, and has made a bet to circumnavigate the globe.

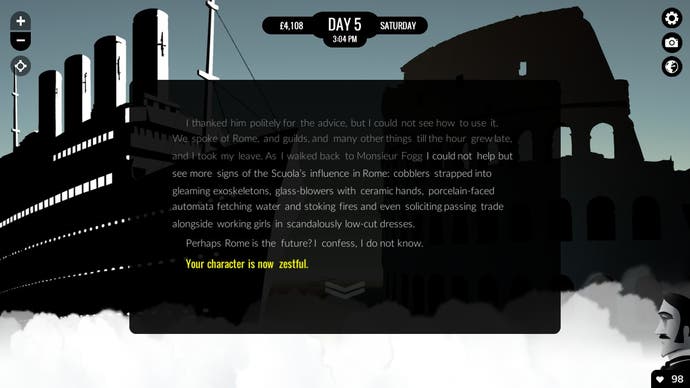

Through player choice, Passporteau can be a brusque, business-like gentleman, or a fanciful closet revolutionary (and many other points in between), and this emerging personality is largely defined through playing with his internal monologue. Technological progress can be frightening, built on machinery and blood, or something empowering and joyful that enables adventure and social progress. The scale of choice, and the opportunities that are provided, means there are rich opportunities for roleplaying what kind of a valet Passporteau is, something which is lampshaded by the occasional declaration that you are now 'Sauve', 'Zestful' or 'Dependable'.

As the player moves into their second or third playthrough, however, you start to be given the option to define and shape Passporteau's past, rather than just his experience of the present and the future. Familiarity with the world built up in the first playthrough gives way to shaping how Passporteau got to that inciting instance of being whisked away by a mad Englishman in the first place. Paris is the first city 80 Days takes you to on your initial playthrough, and the game leads you around a World's Fair which showcases the technological marvels and conflicts of its steampunk-inflected postcolonialist landscape.

When you return for a second trip around the globe, however, you're given an opportunity to explore Passporteau's part in the recently passed Siege of Paris instead, and are transported back through his memories. At this point you've been with Passporteau for hours, but now you're going deeper and deciding the shape of his past.

This single sequence, which moves through the war and the destruction of Paris, before curving back around to the Paris of Passporteau's youth as he rebuilds it in his mind, is not as choice-driven as the beginning of Mass Effect or most other narrative-led RPGs. Only one or two small elements of Passporteau's past are ultimately defined but, like Darklands' character creator or the beginning of a tabletop roleplaying campaign, the whole thing serves to immerse you in that moment through small choices. It puts you in the instance of experience, rather than just telling you the facts. In doing so, it give you a chance to define who you are in tiny, realistic increments rather than deciding on your whole history in one go.