Why the Call of Duty brand can't compete with Star Wars

People can't tell military shooters apart, brand expert says.

The Call of Duty franchise might have made more money than the likes of Star Wars and Lord of the Rings at the box office, but it still has a long way to go before it overtakes them as a brand.

That's the verdict of one of the UK's leading brand experts, who said most people struggle to tell military shooters apart.

Activision's Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 last week enjoyed the biggest entertainment launch of all time.

Backed by an unprecedented advertising campaign it generated an incredible $750 million in sales in just five days. After 24 hours on sale it had sold 6.5 million copies in the US and UK alone.

Life-to-date sales for the Call of Duty franchise exceed worldwide theatrical box office for Star Wars and Lord of the Rings, and in the UK, the money made by Modern Warfare 3 and Black Ops in their opening weeks was greater than the combined opening weekends of all eight Harry Potter films.

But according to Stephen Cheliotis, chief executive of The Centre for Brand Analysis and chairman of the UK Superbrands and CoolBrands Councils, Call of Duty cannot compete with the biggest brands in film because most people think games in the same genre all look the same.

"If you look at awareness they're not quite up there with the likes of Star Wars or Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings," he told Eurogamer. "Outside of the real keen gamers there's a bit of confusion between different types of game franchises.

"For those that are part-time gamers or loosely interested but not necessarily real keen players, they mould a little bit into one. With the latest release, they say, is that part of that franchise or is it that one? I can't really remember.

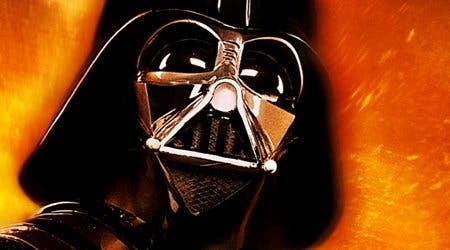

"There aren't many people who struggle to tell the difference between Star Wars and Lord of the Rings, or Harry Potter and Twilight. They're all clearly defined, different propositions. They might be in the same genre, fantasy adventure, but they're clearly distinguished and differentiated.

"With games, unless you're a real follower, you say, I can't remember really. It's just one of those big franchises and it's a military shooter, and they're all kind of the same. I don't think people say, Call of Duty is this, and this other one is that. That's the difference. They blur. That's where you've got a brand issue. There's not much to distinguish them for the average player that's just jumping in and out."

Cheliotis said if he were commissioned by Activision to analyse the Call of Duty brand, he would work on cultivating the personality of the series and focus on one or two areas of the brand proposition.

"Maybe one series is continuously about MI5, or one's consistently about the Royal Navy. Something that says, this is what it is. You can't go, well, I'll be the US today and I'll be Russia tomorrow. Is there a thread that holds that series together that says, this is who we are? Whether that's a person, a unit, a country or a fight, maybe set in different times or scenarios, you're always the same side having the same fight. That could be the glue.

"I still think [games] all blur into one. For your casual gamer walking into Tesco, and just buying their game alongside their milk and veg, there's a bit of, oh, I don't know if that's for me."

Stephen Cheliotis, CEO, The Centre for Brand Analysis

"How do people say, that's clearly that game? If you've got a still of one of those films, straight away you say, that's that. If you have a still from Call of Duty versus another military franchise, unless you are a real discerning follower, you'll probably say, oh, I don't know. It could be Call of Duty or Battlefield."

Call of Duty is, by a huge margin, the most successful franchise the industry has to offer. It is the fastest-selling, best-selling and highest grossing video game. But there is still plenty of room for growth, Cheliotis said, if Activision works on the brand and expands its social aspects.

However, he warned Activision against trying to make Call of Duty a catch-em-all brand, appealing to all types of people. This, he said, could have a negative impact.

"There is a danger that it becomes so generic it's a bit of everything for everyone," Cheliotis said. "When you're doing brand analysis, it's good that some people don't like you. It means you have a point. It creates longevity and doesn't mean you're a jack of all trades. If you've got something that's so generic and bland and dull that everyone might like it, then you're in the longer term in danger of being so catch-em-all that you're not creating long-term followers.

"They might be better off focusing on what they're really good at and hone that down and be known for that."

The game industry faces a difficult job improving its brand awareness, Cheliotis said. Only Nintendo with Mario and Sega with Sonic have achieved anything approaching success in this regard.

"It's a real struggle with games. You've got Sonic. You've got Mario. You haven't got a lot of other brands that are truly distinctive and stand out. You might have a few point in time ones, but generally, as long term brands that have longevity and true differentiation, there are not many examples.

"When you think that the industry is bigger than music and film, it's quite surprising.

"They're clearly massive successes, and they've got decent awareness and familiarity. They do cut through more than they used to in terms of across the board different demographics, but I still think they all blur into one. For your casual gamer walking into Tesco, and just buying their game alongside their milk and veg, there's a bit of, oh, I don't know if that's for me."