World of Goo

IGF 2008 Finalists: Exclusive pre-goo.

Towards the end of February, San Francisco hosts the Game Developers Conference, where you can spend the morning listening to someone talk about visual storytelling and the afternoon watching people argue about font rendering. Around the same time, we also get to visit the Independent Games Festival, where the best indie devs in the world gather to show off. And yet we don't celebrate them half as much. So we thought we'd put that right, with a few hands-on previews of the best the IGF has to offer. First up, an exclusive look at 2D Boy's World of Goo. Take it away, Kieron.

Having played through the preview code of this, the first twenty percent of the full game, I found myself desperately looking around for someone to tell about the thing. Except it was after 1am and no-one was awake, so I just paced and growled and generally acted as if someone had put a bunch of termites inside my head, and I had no way of getting them out. Thank the Lord of Eurogamer that I get to tell you lot about it, as otherwise it'd be straightjacket time.

World of Goo is about sticking Goo together. It's as instantly charismatic a character-lead puzzle game I've played since the first Lemmings way back in the days of the Amiga. Older readers will remember that first time: the absolute sense of wonder in mass of suicidal rodents, the wit of the animation, the sheer chaos that resulted from failing (or even, often, succeeding), the instant impression of being presented with something absolutely coherent and joyous. World of Goo's like that. Hell, I was smiling from the second the developer's "2D Boy" logo splashed itself on the screen with agreeably brash confidence.

See - fanboyism from a bloody splash screen. And I'm not even drunk, for once.

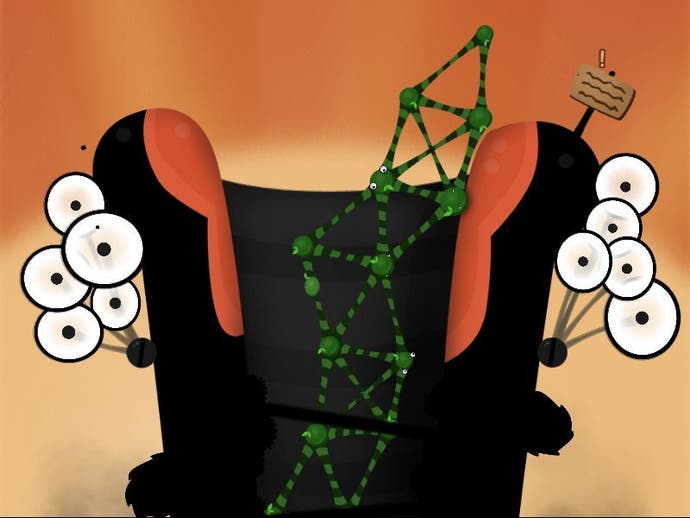

World of Goo is, along with Crayon Physics Deluxe, one of the two Independent Game Finalists born of the principles of the Experimental Gameplay Project. The EGF is based on three concepts: all of the games are made in a week, they're made by one person, and each game is based on a single common concept. And, as the name suggests, they're experimental. Kyle Gabler's game was the web-hit Tower of Goo, based on trying to create a structure made of goo-balls as high as possible. Since the connections that appear between balls stretch and contract, it's trickier than you may initially think. The higher you get, the more imbalances in the structure are going to start the thing swaying, forcing you to try and work out a way to hurriedly counteract it, leading to another imbalance and so on, until eventually the whole thing collapses in a big gooey mess. According to my friends who work in the highly competitive goo-construction industry, this is highly accurate simulation of what it's like to build of Tower out of Goo.

World of Goo manages to expand the basic physics-goo manipulation into a whole game. They do so in such a naturalistic way that when a level that's just a crafty nod to the basic Tower of Goo gameplay arrives it only underlines how far they've come.

It's the result of Kyle and Ron Carmel - both EA veterans running! running as fast as they can! - forming a two-man development team called 2D Boy to do the gig. The thing which immediately hits you is an aesthetic one - it's a strikingly attractive game, which looks and sounds easily as slick as most mainstream games. The main gaming reference is Double Fine's much loved Psychonauts in terms of a a warped, cute-yet-wrong fantasia. I'd argue they even push it further. Since each level is a single contained area, 2D Boy has been able to turn each into something with a distinct sense of its own place. Levels happily drop colours, or play in silhouette, or take place in situations like the stomach of an enormous beast - all, brilliantly, tied into a plot - and generally do their best to be memorable.

And it's not just in terms of looks. At least in the preview code, each level is its own distinct thing, with a challenge which may include tools you've previously learned, but given an absolute singular spin. What made me laugh hardest was a level which did that literally, setting you the task of trying to build a tower towards a stationary pipe in a chamber that perpetually revolves, so demanding you make something which rolls. You're left worrying whether the thing will fall apart as it flexes and totters and generally acts much like a goo-based structure would do if put in a tumble-dryer.

The game's also expanded in terms of the available tools. For example, there are multiple sorts of goo, each with their own unique property. The traditional ones which, when placed, remain forever, remain a standard, but other varieties appear, like ones that can be detached and used repeatedly. In a level with a limited amount of detachable goo, you're left doing things like wondering which goo blob you can remove from your structure to reach the exit without causing the whole thing to come tumbling down. Another example, the balloon-goo, give a different spin entirely to the physics - they're lighter than air, so can be used to lift other goo or obstacles. You also see things like sleeping goo being placed on the map, which can be awoken if you get near for sticky reinforcements. And, obviously, things are made more dangerous by destructive scenery, which you have to avoid before your goo is turned to (er) goo.

The game encourages you to replay levels to maximise goo-rescue by including a particularly appealing meta-game. All the goo over the basic number you're required to save on any given level is deposited on its own screen, where you're tasked with building the highest tower you can. This is enlivened by the clouds in the sky, each marked with another player's name, showing how high other World of Goo players have reached. It's a particularly literal high-score ladder - and one with the charm that the person with the top score can, if they get over-ambitious in their climbing, find themselves plummeting down the rankings as their goo structure plummets down the screen.

Reservations are thankfully minor at this stage. The restart button is on a menu you have to bring up, and - when rapidly experimenting - I'd rather press a hot button just to have another crack as soon as possible. On the meta-game, when your tower has collapsed, I can't find a control for making all your goo bits disassociate from one another, meaning you have to dismantle it by hand if you want to have a clean crack at the skies instead of building on the wreckage of your failures. Also, if you place a goo over the in-game signs which provide information on the level, you can - when trying to move it - easily be dumped into some (humorous) instruction screens you have to click through. Really: minor, minor stuff.

The only real question is whether the wit and innovation can be kept up across the full game. You really have to hope so.

World of Goo is due for release on Valentine's Day, with Mac, Linux and Wii versions to follow. The PC version is availble for pre-order from 2D Boy's site with free-profanity pack. No, really.