World of silence: Lumines' brilliance remains revolutionary

Music fusion.

Today, if you start playing a game on your smartphone that places a heavy emphasis on music and sound, chances are you'll receive an advisory warning. It'll ask you to please insert your headphones for the "best experience". It doesn't matter if you're home alone on the sofa or your head is scrunched between numerous standing thighs on public transport, headphones are important. And we can all blame this warning on Lumines and the way it helped change our relationship with games.

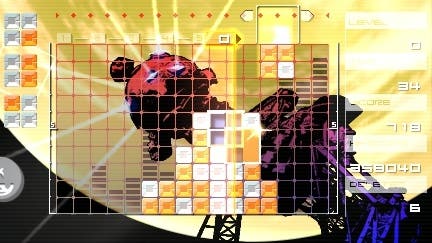

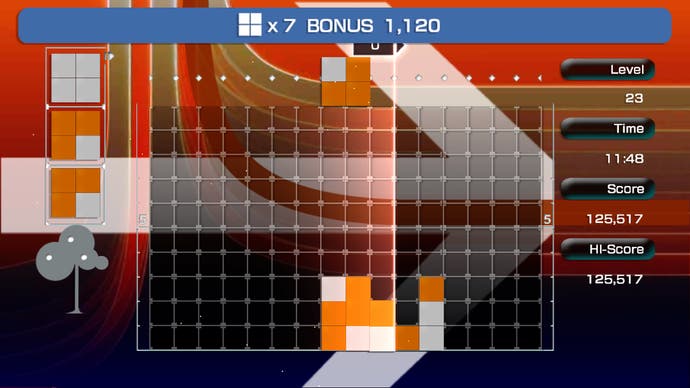

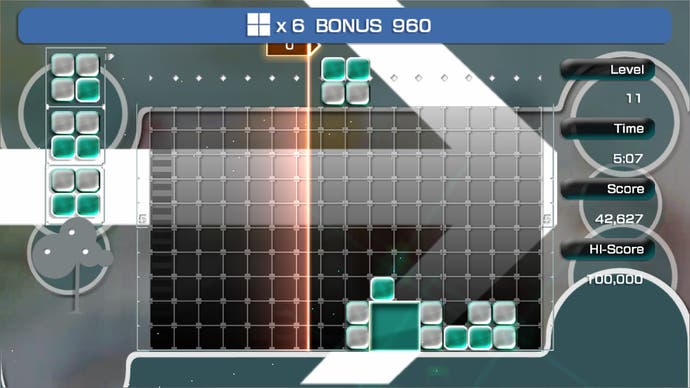

Apart from dance and instrument-based entries, successful music games are bloody hard to make, regardless of their soundtrack listings. In Lumines, you guide four-bricked squares down a large grid, each brick made from one of two colours. Your goal is to shuffle the colour orientation and make new, identically-coloured squares that vanish in this grid before it becomes too full. However, each button press creates a sound and the music will continuously change along with the brick and background colours, inducing a unique form of synaesthesia.

As with any puzzle game description, it sounds (pun intended) pretty tedious compared to seeing this delight with your own eyes. My first time playing was in the backseat of a Nissan Micra on the PSP's launch day, sitting in the Toys R Us car park (RIP) as my brother went to purchase a different Sony product. It might not seem ideal, but I knew then just how groundbreaking all of this was.

Sony's goal wasn't to simply challenge Nintendo in the handheld gaming world with the PSP, it was to get older gamers playing on the go. For instance, the gory action of God of War and GTA were subsequently released on the handheld, while Nintendogs took advantage of everyone's (including younger gamers') adoration of digital pets on the DS.

Lumines was successful for providing a completely refined experience in a very premium multimedia device. It's also particularly well thought out as a game, following certain tropes you see in platform games like Donkey Kong or Crash Bandicoot, despite being so original. For example, there's a grid stylised with cool colours and snowflake effects at one point, and another with bright, bold colours accompanied by groovy reggae.

These environmental changes help bring a forced sense of variety in other games but feel so effortless here. In fact (cue humblebrag), I've never noticed the changes to the information around the grid until I recently replayed the game, seeing the score increase thanks to my deep-seated block-busting abilities. Other touches are more noticeable, like the electrical gong induced by the pause button, or the way images in the background dissolve back and forth but never lure our attention away from the grid and falling blocks.

But the music holds the centre stage in Lumines, taking your senses into overdrive. Our relationship with music in games is so strange and varied, on the one hand admiring the orchestral score of the first Halo game yet enjoying the evergreen classics from the 80s in GTA: Vice City. My own tastes were evolving when I first played Lumines as a teenager, which must have played a role in my eventual sympathy for electro-pop, but thankfully, not techno. The songs chosen in the game cover a wide range, not only the obvious rock and dance genres but colourful disco and haunting acoustics, contrasting with the ever-changing speed of gameplay.

The first song is a masterly choice and has become synonymous with the series. Mondo Grosso's Shinin' induces so much excitement, making me feel a spectrum of emotions from elation to melancholy, with lyrics such as "world of silence, blinkin' farthest light" and "unbearable pain, melt into the rain". This hints at the intimate experience taking place within your hands, screen shining and shining, that somehow also feels boundless.

This freedom, later fully realised in Rez Infinite, is what legendary designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi is always aiming for. In the gaming sphere, all of our senses are available as targets, whether it's Sega Rally in an arcade or Child of Eden with the Kinect camera.

Watching TV and films is incredibly passive, and reading is arguably the most seclusive form of media consumption. But music is where we dance, choose frantically and indecisively in the car, or talk over while shopping with others. That's why playing Lumines secluded with headphones is not where all games should be, despite the extinction of local multiplayer gaming being so visible on the horizon. In fact, even Mizuguchi thinks gaming is both a social and personal experience, and remains optimistic of the ways in which augmented/mixed/virtual (delete according to whichever wins) reality will help us engage with one another better.

Very few puzzle games have come close to achieving the same recognition of both simplicity and brilliance over the years since. The only thing that comes to mind is Threes! and its addictive charm, showing just how difficult it is to crack this genre. Although Lumines' debut in 2004 (2005 in North America and Europe) seems like a fading memory now, it was the only true original in a year of admittedly brilliant sequels: Half-Life 2, Halo 2, Burnout 3 and World of Warcraft, among others.

My editor and I talked about our experiences of meeting Mizuguchi, his kindness and elegance, and the way he thinks deeply before answering questions, an odd juxtaposition given the frenetic nature of his games. The care and attention given to his games is very obvious, and Lumines is no different, remaining a pocket-sized masterpiece for well over a decade. It envelopes all of the joys of gaming, with glittering visuals and explosive sounds. This all occurs in harmony as we quickly tap away at powerful handheld devices that provide a multitude of feelings few other things can offer, all while surrounded by silence, our senses ready for new experiences.