You, me and the cube

A day in the office with Curiosity - What's Inside the Cube.

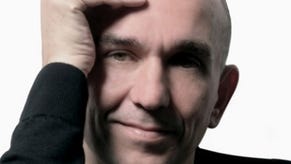

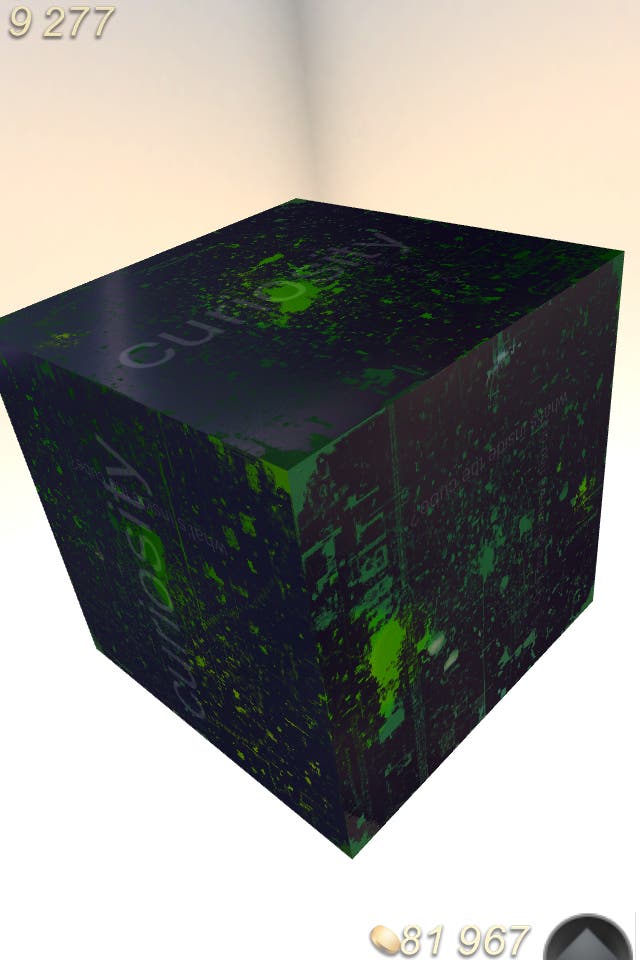

I initially tried not to read too much about Curiosity, the latest game/experiment/happening from Peter Molyneux and his new studio, 22Cans. What's there to read about after all? It's a virtual cube, floating in virtual space, and you tap away at its surface. Meanwhile, scattered around the globe, everyone else is tapping away at its surface too, burrowing through its shiny skin one layer at a time. There's something special inside the cube, apparently, and a single person's going to get at it. It's basically a massively-multiplayer spin on the Christmas cracker - and I've never really felt the need to read too much about those, either.

I've given in, though. I read one interview just to prove to myself that I was correct to ignore it all, and then another to celebrate proving myself correct so boldly. Then another, and another, and another. In the end, I've pretty much read everything that's been written about the project.

Now that I've also played Curiosity - as much as anyone on the planet is going to play this thing - I'm glad I did all that reading. I suspect that the reading is kind of the main event with Curiosity, in fact, just as Tom Wolfe once argued that the torturous critical theory is the main event in much modern art, and that the museums and galleries should really reverse things to get the full effect: massive, wall-filling chunks of academic text accompanied by tiny little photos of the paintings and sculptures themselves to illustrate it all.

Where was I? Oh, yes: I was tapping on a cube. So were you, most likely. Tapping away out of intrigue, boredom, a desire to be annoyed by the bold mindlessness of the whole thing, or horrified by the glorious manipulation of it all. Is Molyneux indulging us with this? Is he testing us? Is he doing tests on us, seeing how far that massive extrinsic reward - there's something life-changing up for grabs here - can make up for the limited intrinsic pleasures of, well, tapping?

I wonder whether we'd tap-tap-tap even if there were no reward - it's Molyneux, after all. Curiosity's a big mysterious cube, and each cubelet disappears beneath your finger with a pleasing crumble of graphite. There are combos and nice little bonuses to pick up for clearing a screen, and you earn coins that can be spent on a selection of power-ups. I spent 115,000 of them on a bomb, as it happens. Eight seconds of moderately improved destruction. People in the office gathered around while I set it off. Bigger taps!

That moment aside, I'm not getting a huge sense of a genuine shared experience as we all chip away at this thing, even as I see strangers' graffiti all around me, or use Facebook to warp to the spots where my friends are busy at the virtual coalface. Maybe it's the lag, maybe it's the scratch-card sheen of the first layer, which brings a tinge of the off-license cash register queue to proceedings: I don't yet feel a kindred spirit to the thousands of others tapping and tapping around the world, just as I didn't with hundreds of thousands of others who once wanted to know who shot JR or where that golden hare from Masquerade was buried. The most interesting thing about Curiosity is perhaps its strange view of community - all of us working together while many of us hope that we're the one - the only one - who actually benefits from the whole enterprise.

So what's in the cube? What could it be? Jet-pack blueprints? Monster Truck lessons? Nolan North? An interview slot with the pope? Something biblical, something allegorical, something universal, surely, but also something with the salty tang of Groupon, or of Wheel of Fortune to it. It's so big you'll be on the news, apparently.

We all know what's truly in there, of course. Peter Molyneux is. He's in every cubelet and every polygon, in every data package that zips back and forth and in every electron that's molested as the whole thing ticks along to its conclusion. In an odd manner, Curiosity's one of the most waywardly egocentric games ever made. It might be predominantly featureless, largely textless, and lacking any kind of overt human element, but if you know about its background it's also impossible to play the game - not that it really feels like a game or you like a player - without thinking about Molyneux constantly. Molyneux let loose from Microsoft, Molyneux back to his old tricks. Huckster, impresario and genius, colleague of Barnum as much as Braben or Miyamoto. Molyneux is the cube, just as Kubrick, that other great manipulator, was the Monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Actually, I would have quite liked to tap away at the Monolith.

And still we prod and we poke, and we go away and then come back to see how much prodding and poking there is left to do. Isn't this a significant part of what a certain species of game design is these days? They make something for us, and we wreck it.

I don't mind wrecking it, on balance. I like the fact that when you zoom in really close on Curiosity, it all becomes rather physical, each tap knocking the cubelets to either side gently out of alignment. This is going to be part of our lives for a short while. Maybe we'll even miss it when it's gone.

Somewhere, I hear laughter. He's done it again, I guess.