Mass Effect: Andromeda review

Bumpy Ryder.

You've barely laid eyes on the kett before you're looting their corpses, filling your pockets with gun parts, credit chips and omni-sellable "salvage" items wrapped in pointless flavour text. You've hardly swapped greetings with the angara - the friendliest of Andromeda's three new species - before you're running errands for them, dropping off lunch for resistance fighters or plunging through purple jungles in search of a scientist's mislaid revision notes.

If there's any genuine mystery or intrigue to the idea of travelling 2.5 million lightyears to colonise another galaxy, BioWare's fourth Mass Effect smacks it over the head with a prospector's shovel and boots it out the airlock during the first few hours of play. You're left with a zesty but unsurprising third-person shooter mired in a soup of mundane chores - a game of mesmerising, gargantuan landscapes sabotaged by mixed writing and (at the time of review) an astonishing quantity of bugs. Perhaps above all, there's a shortage of drama or real consequence to Andromeda, apparently brought on by the shift to an open world template, that is sadly new to Mass Effect - a series celebrated not merely for its freedom of choice, but for making those choices matter.

The campaign is a hybrid of Mass Effect 1's galactic whodunnit and the sprawling, state-building elements from Dragon Age: Inquisition. You play Scott or Sara Ryder, a youthful pioneer aboard the human colony ship Hyperion who is unexpectedly (well, providing you haven't played a BioWare RPG before) thrust into the role of "Pathfinder" - a being of unlimited extrajudicial authority, tasked with prepping planets for settlement by grinding side missions while probing the secrets of yet another vanished civilisation, the Remnant, and duffing up an armada of space fascists led by ET's edgelord cousin.

Along for the ride are the original trilogy's salarians (frog scientists), krogans (fatter Klingons), turians (military crabs) and asari (pansexual elves), most of them lodged aboard the Nexus - a gigantic orbital shopping mall that is essentially the first game's Citadel with more fetch quests and fewer erotic dancers. New to the proceedings are the angarans, the stereotypical tribalist natives who supposedly wear their emotions on the surface, not that the game's character animations really bear this trait out. Regrettably, some of Mass Effect's more unusual races have been left in the void, including the elcor and hanar. I was especially disappointed to find little trace of the quarians, a society of former slave-owners forced into exile by their robot creations - surely a species that has a lot to contribute to a story about finding a new home.

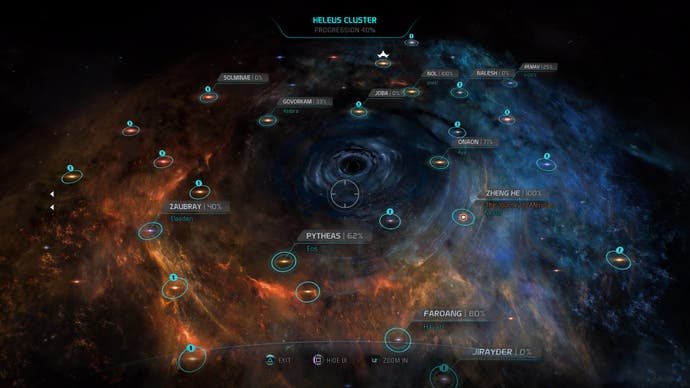

Much of the campaign sees you weighing the claims of rival factions, picking favourites or thrashing out compromises - a process that also affects crew relationships aboard the Tempest, your snazzy private scout ship/shag pad, and determines which factions you'll bring along to the final battle with the kett. Among the quandaries you'll face are whether to found a military or scientific outpost on your first colony world, whether to censor toxic communiques from the angarans to the Nexus, and whether to gift a grumpy krogan leader a potent Remnant artefact. As with previous games there's a nice sense of chemistry between the little and the large, between the conversational minutiae of Andromeda's bustling community centres and the rumbling wheels of statecraft.

Unfortunately, many of the key dilemmas recycle well-trodden conceits from the original trilogy and RPGs at large - yes, the salarians and krogans are still at each other's throats over the genophage, and yes, you'll be asked to decide the fate of a possibly innocent convict. Other decisions are revealed to be of small import in hindsight, which reflects both the relative weakness of the writing and a broader structural shift - away from the flexible yet impactful narratives of previous games and towards the spineless, anything-goes tepidity of an open world.

Where the original Mass Effect games kept you moving through the story, Andromeda relegates its critical path to second place, offering up a spread of loosely associated scenarios that just happens to include a fairly uninspired tussle with a genocidal tyrant. It's a game that is more interested in keeping you busy than keeping you in suspense about what happens next, or making you feel the consequences of your actions. There are comparatively few hard decisions to be made in the course of the story - nothing that deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as, say, Mass Effect 1's Virmire mission - and many quests (including character loyalty missions, of which more shortly) are designed to be playable at any point in the campaign, regardless of the broader stakes.

The lion's share of Andromeda's missions are busywork - go to a waypoint, scan 10 Remnant collapsible shelving units with your ugly wrist-mounted display, scoop up five mineral deposits for some lazy boffin back on the Nexus, blow up three raider outposts, and so forth. The game's partiality for such insipid fare is made all the worse by some needless toing-and-froing - this is a universe with FTL communications and cranial AI implants, but you can't check your email, pick a weapon prototype to research or take a vidcall without heading home to the Tempest. More aggravating still is the act of travelling between planets and solar systems, a janky, unskippable 20 second cinematic which feels like some animator's pet project that nobody had the heart to erase.

Andromeda's longer missions claw back a little goodwill. To fully colonise planets you'll need to crack the lid on a Remnant vault - a dungeon made up of switch-and-platform puzzles and synthetic defences that houses a massive terraforming apparatus. The reliance on sudoku-style glyph puzzles to unlock vault entrances gets old fast, as does the obsessively geometric décor, but the setups themselves are varied enough to hold your attention. One vault might see you sneaking around a quadrupedal mech to hack a turret or raise some motorised barricades. Another has you darting between air-conditioned bubbles to survive in sub-zero temperatures. These escapades are rarely majestic, but they're a foundation the rest of the game might have built on.

The same goes for some of the objectives doled out by squad mates - as in previous games, you can help allies out with personal difficulties to unlock their top-tier abilities and perhaps, a romantic encounter. Among the better character-specific missions are a trip to a shattered moon to rescue a juvenile hacker from a gang of smugglers, disabling or enabling terrain variables through CCTV cameras to change the odds in the ensuing battle. But where previous games made recruiting a full squad integral to the story, obliging you to learn about potential companions from afar and earn their trust, Andromeda hands you everybody on a platter early on, and the characters themselves are a mixed bag.

Angaran chum Jaal is probably the standout - a fierce yet self-deprecating individual whose dialogue includes a few predictable but well-delivered jokes about cultural and linguistic differences. Among my favourite interactions with him is an email specifying his dietary needs aboard the Tempest, including a variety of facecreams and "25 jugs of nourishment paste", ending with the magnificently haughty "I hope this list is compliant". Less winningly there's ex-cop Liam, a needy bestbro who lives on a sofa near the Tempest's engine room, and Peebee, a sociopathic screwball who is Dragon Age: Inquisition's Sera with half the wickedness and twice the midriff. Worst of all is SAM, your inescapable AI assistant, who exists mostly to nudge players towards scannable objects or witter about mining opportunities (a simple find-the-deposit minigame) as you hurtle through the wilderness in your Nomad all-terrain rover.

A wider problem with Andromeda's writing is BioWare's failure to convincingly replace the old Paragon/Renegade system, which awarded points for Nice and Nasty dialogue choices or actions. As a way of thinking about ethics Paragon/Renegade is obviously very clunky, but as a dramatic device it creates strong pivotal moments in dialogue while underlining the effects of your decisions over time. Andromeda's equivalent, a four-way split between rational, emotional, casual and professional options, is relatively non-committal. It's basically the choice between bored Ryder, soppy Ryder, flip Ryder and parent Ryder, neither of whom are really worth getting to know.

The script has moments of sparkle. At one point I gave a somewhat mechanical speech at the Nexus, only for a salarian bureaucrat to pick me up on it sarcastically, and there are some cracking diary entries to find on Andromeda's innumerable terminals - krogan sex therapists advising clients about dating sims, or an excited email from Drack about what turns out to be a phishing scam. It's largely pedestrian stuff, however, filled with gotta-do-what-you-gotta-do folksiness about new frontiers, inconsistent application of your ship's universal translator, and the odd Destiny-esque clanger.

The last of Mass Effect: Andromeda's major shortcomings is, I hope, a temporary fixture: this is one of the most technically uneven games I've ever reviewed, though also one of the more beautiful. On a good day you can expect frequent texture pop-in, facial animations that run the gamut from "just had my Botox" to "quick, phone the exorcist", and performance that sags from 30 frames a second into what feels like single digits. And on a bad day? Well, where to begin. The least bothersome bugs include enemies getting stuck in mid-air after leaping out of dropships, or trapped inside objects. Further up the scale of severity, I've encountered the odd piece of dialogue audio that won't play, dooming the participants to an eternal stare-off, and a boss that spawns hundreds of metres from where the script suggests it should appear, as though hurrying back from a cheeky cigarette break.

There are even a couple of outright progression-killers in there - I was unable to finish one major sidequest because the game refused to display the prompt that lets you board the starship in question. At another point I was unable to die, seemingly because Andromeda had decided that I needed to revive a squadmate before it could show me the mission failure screen. Many of these issues will be patched out, and most are negligible - easily forgiven as you gaze out over a gleaming, windswept icefield studded with kett outposts, or glimpse a gigantic sandworm composed of flickering black shards arching through the skies of a desert world. But it's staggering, nonetheless, that the game made it to retail in this state.

Andromeda's belated saving grace proves to be its combat, which takes the arsenal of guns and abilities from previous entries and introduces a boost jump, jet-dashing and an unprecedented (and initially impenetrable) array of gear-crafting options. Your almost total lack of control over comrades is irksome, as is being limited to three active abilities at once, but there's great fun to be had nonetheless trying out barmy custom guns and esoteric ability combos on the game's roster of aerial beam cannons, bullet sponge juggernauts and cloaking sharpshooters.

My default tactic is to lob a gravitational singularity at the nearest group, hoiking unshielded foes out of cover, before using my telekinetic abilities to barrel into them at supersonic speed. If anything's left upright, I'll teleport to safety and either hurl down a turret or bust out my most cherished weapon, a sniper rifle that fires cluster bombs. The game's character progression systems are straightforward - you plug points into skill trees to unlock and upgrade abilities - but it's distinguished by a "profile" feature that allows you to switch up your overall capabilities on the fly, picking Infiltrator to trade your evasive warp for a cloak, or Adept to expand the reach and savagery of your area-of-effect skills. All told, there's a charisma to this side of the game that goes a long way, though taking a serious interest in crafting does, admittedly, mean you'll have to spend more time trawling those world maps for loot chests and scrap.

In some respects, Andromeda is most disappointing when it's at its best. There's a mission in the opening third that conjures up the spectre of Virmire - a raid on a kett facility, accompanied by a crack squad of angaran guerrillas. The shift in mood and focus is faintly miraculous: the music kicks up, the bugs ease off, the dialogue straightens out of its slouch and the combat goes into overdrive. There are familiar but pleasantly ghoulish secrets to uncover, rooms to comb for hints about kett society, and a couple of heated, deftly worded interactions with companions that genuinely get your blood pumping.

It's gripping stuff, and a reminder of the greatness of the Mass Effect trilogy - its intelligent reworkings of pulp sci-fi cliche, the taut splendour of its scenarios and aesthetic, the colour and dexterity of its writing. All that's still in here somewhere, I think. But then you pop out the other end of the mission, back into Andromeda's labyrinth of drudgery and obfuscation, and remember that you're a long way from home.