An interview with Cyberpunk creator Mike Pondsmith

"You babysit the baby for a while."

R. Talsorian Games is having a pretty big year. The studio is riding high on the release of The Witcher RPG last year, with expansion Lords and Land in the works. Cyberpunk Red, the latest edition of the Cyberpunk tabletop RPG is releasing in August, 15 years after Cyberpunk V3.0. And, of course, Cyberpunk 2077 played a starring role in this year's E3.

Cyberpunk creator and tabletop industry veteran Mike Pondsmith was at the show, mirrored sunglasses and all, so we sat down to talk about Cyberpunk Red, netrunning, that poster and sending CD Projekt Red back to the drawing board on guns.

So, exciting times for R. Talsorian right now...

Mike Pondsmith: Pretty exciting.

Quite a lot going on!

Mike Pondsmith: Yeah and if I get some sleep I'll let you know!

So obviously Cyberpunk is something you've been at the helm of for as long as I've been alive actually.

Mike Pondsmith: Oh boy yeah make me feel young, oh yeah!

But R. Talsorian is about to put out the next chapter in the Cyberpunk story and 2077 is further on down the timeline from that so at this point I feel like it's relevant to ask again, what is Cyberpunk to you? Has that definition changed at all?

Mike Pondsmith: No. What I have realised is between us, CD has designed a new form of Cyberpunk. Cyberpunk has had a tendency to be mostly intellectual in style and nature, it's a very thinkative kind of thing. I love Blade Runner for example, but Blade Runner is a movie that is basically philosophical more than anything, and 2048 is even more so. You know, it's just 'you want big questions with an occasional gunfight'.

And the other way is Mad Max, 'you know I go out and I shoot things and I have weird special effects.' What we've found is to get both of those in there in a better mix, and I'll be interested to see what happens in the genre because I think the genre up to know has played all the variations out of it. What we have is kind of heroic cyberpunk, that isn't totally stupid, you know, 'hey I've got a gun blam blam,' and ask some of the questions but doesn't stop to mull over them as much.

There's a scene in the trailer today I was looking at where V looks down at their hands and they're doing something or other and if you play it right, as your V is looking down you realise your hands are essentially metal things all the way past your arms and they have joints and clicky weird things and all that, and it should strike you at that moment that both my hands have been cut off all the way to my shoulders and I have these metal attachments... how do I really feel about that? That's kinda weird, do I feel things, do I touch things, do I feel creepy about it? How do I deal with it? And that's something we don't think about.

Cyberpunk 2077 is set later on than Red, so I guess this is one of the first times the way the property is presented has been out of your sole creative oversight, right? But also you're about to bring out an RPG that's bridging a gap, so are you influencing one another?

Mike Pondsmith: Oh yeah.

What are you taking from 2077?

Mike Pondsmith: Somewhere in the beginning of this but particularly in the last two years we said 'we want to end up like this, how do we get from this to that?' And it was a lucky break because the entire fourth corporate war had been designed by us years ago to change up characters and to start a new arc.

We always looked at Cyberpunk as being like a comic book. So we had finished the first arc, the 2013 arc, we're through the second arc and we're going to be going into another arc and 2077 gave us a new way to do it. So that began a collaboration where we'd say, okay well we wanna have this character alive 60 years from now. What do you wanna have them do? Well we want them to do this. Okay, but we need to have you do this character over here and show how they got built up to here. Okay, and can we bring this character back? Yeah, here's a way I figured out how to bring this character in or whatever. And you have to understand a lot of this stuff we planned in Talsorian years ago - case in point, there are certain characters that are supposed to be dead but technically nobody knows for sure that they're dead. You know? Nobody has actually gone and checked for a heartbeat. So, who knows?

So it's been very collaborative. I'll give you an example, I was over in Warsaw about... I guess this must have been two years ago, maybe three, and people were showing me guns. And the guns were these silver Star Wars-y things and I went no, Cyberpunk guns don't look like that. You know, they're large, they're black, they're brutal, they have rails, they have this, they have that, and so I literally had a long discussion with all of the weapons guys and a bunch of people in the studio.

They went out and built a wall of real world guns, which is awesome I'd like to point out, and they had begun to see why the guns in our game work, because they're built in a real world context, not a science fiction context. You know almost everything we do, we do really solid research on and make sure it works. So what that got us was the guns we're seeing now. They go, 'yeah this is an acceptable idea for what a gun would be.' So that's a collaborative thing. And then they in-turn come back to me and go, 'what if we could do this?' and I go, 'yeah I think we can fit that into '77 and going into Red,' so it goes back and forth.

It's not like I handed the baby to them and said I'll never see it again. It was more like, okay well you babysit the baby for a while and then I babysit the baby and we, you know, trade back and forth. And if I catch him smoking it's your fault.

[Laughs] excellent. Last year after the demo was released, William Gibson said some fairly dismissive things about it. How did that make you feel?

Mike Pondsmith: Eh, not bad. You've gotta understand this - for one thing I think he's a hell of a writer. As I said years ago when I first read his stuff, and unfortunately I read it after I had written Cyberpunk which was really weird, you know I said this guy's stuff is so good it makes my teeth hurt. But it's hard for him to make any judgement call on what he saw immediately, so he's kinda jumping to conclusions, but also, you know, it's his opinion. I do what I do, he does what he does.

Sure. So obviously in the demo that's being shown at E3 right now we're getting our first glimpse at how Netrunning works.

Mike Pondsmith: Which I was really happy about because I spent a lot of time working that out with everybody.

You've pre-empted my question: what were the pillars that were really important for you to hit?

Mike Pondsmith: The biggest problem with Netrunning right now [in Cyberpunk 2020], is oddly enough the Gibson-esque worldview of Netrunning, which is you go out into a vast cyberspace, you fly around and you do things. Case [the protagonist in Gibson's famous novel Neuromancer] works doing that because that's pretty much what everybody does. But if you do that in the context of a game, everybody goes, 'okay I'm gonna go get a beer, Netrunner's going in, anybody need pizza?' and they're gone. So one of the biggest things for us when we went into it was we needed to get the net back into a box that was usable. To that, and you'll see this extremely well done in Red, is we needed to force the Netrunner to be with the group. He can't sit back in his comfy chair with his keyboard and say 'go to the fifth level and open the door'. No, he has to go in there. You have to be under risk.

So I spent a lot of time studying computer architectures and I have two friends who specialise in computer security systems, so I said, 'okay, so tell me how I can screw myself and give me some goal plans here,' and they helped me design stuff that forced the Netrunner to be there, better toward how it works and that sort of thing. It's not super realistic but it's realistic enough. And that informed a lot of what goes on in what you saw today, in that people are doing hacks very close to the runner, they're doing hacks of stuff, they're not flying through cyberspace. When our hero goes to one particular area and they go to the wider net, that is rare. That is insanely rare. That's like saying, 'okay, by the way we're going to now get on the jet plane and we're going to fly to the moon.' It is very much right there, it's gonna come and bite you in the face.

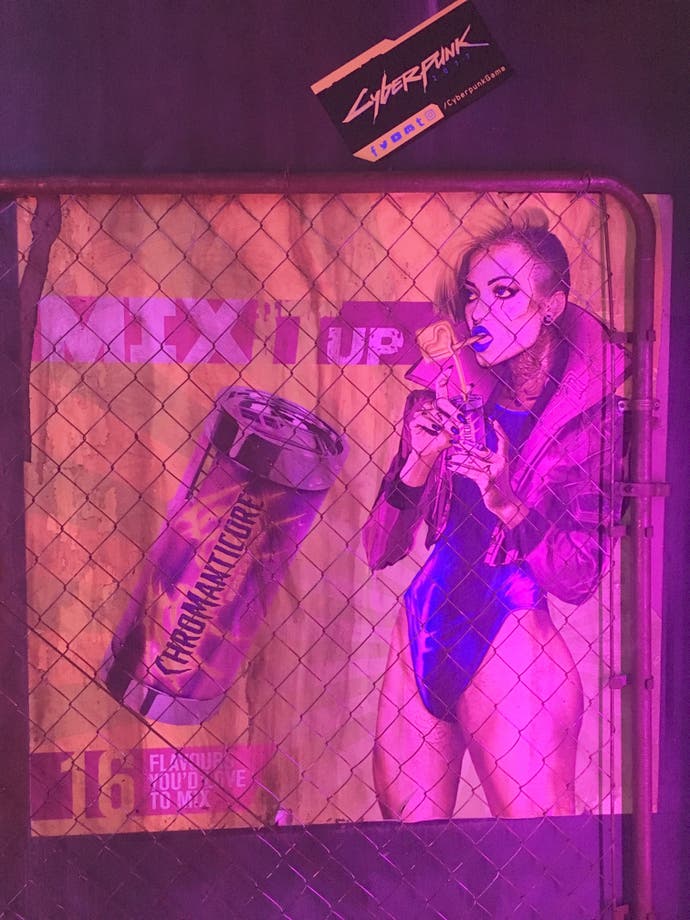

Got it. One last question, I don't know how much influence you've had over the products and advertising in 2077, but there's a poster behind us now for Chromanticore, I don't know if you've seen this. There's currently a bit of a stink kicking up online about it because I think people... do you mind if we walk over? So basically you can see if, I mean, it's saying mix it up and there are lots of flavours you can mix but it clearly looks like a woman who has an enormous penis and I think some people are...

Mike Pondsmith: Uh, I don't see it, but okay that's me.

I think some people are viewing it as potentially transphobic. I was wondering if Chromanticore was anything you'd had any input on?

No, and to be honest I hadn't ever really run across anybody directly here who's got that problem with transphobia, and it sure as hell isn't something that happens at Talsorian. We have trans staffers, I have an insanely large number of friends so for me it's kind of like... what was the issue? So... I don't know. The problem with this is often people come to things with their own interpretations and they may bring those interpretations with them when they examine anything in their world. This could be bad art, this could be a message. It depends on how you interpret it, that's why art is art. It's not, you know, specifically reportage, so consequently the problem with these sorts of situations is that if you approach things in a particular way, you may see things that nobody sees, you may see things that somebody should see, and one of the reasons we have a multilevel culture is because we can see it differently.

Not necessarily to say that's wrong or right but you know, when I look at that, I don't see it. I see, you know, eh, it's not a really good drawing of some woman who's got a coke and my immediate thought was, you know, it's a bad ad, but as far as I know it's supposed to be a bad ad, it's not supposed to be a good ad. You know somebody was hammering it out in a sweatshop somewhere for five dollars.

In the game.

Mike Pondsmith: In the game, yeah. I always figured. So I don't think of it that way and you know, when you mentioned it that would have been the first time I'd even heard of that. What I know is people have brought a lot of interpretations to what we're doing, positive and negative, and they're going to do that and that's sort of inherent not just in whatever we do but also in the nature of Cyberpunk. It's like people arguing about representation of various groups - I kind of look at it as well, you know when I represent people in Cyberpunk they're from every walk of life and every single place and I'm not exactly taking a timeclock to see who's there, I'm going to go, 'does this reflect the world that I see or that I think probably should be out there?' and particularly the world and street - that should be a very complex, very open world because the street doesn't have room to pick sides and differentiate.

Thanks for your time, I hope you don't feel like I was ambushing you with that last question.

Mike Pondsmith: No, it was a bit of a surprise but basically the problem is at a certain point there will be no way or right answer if somebody comes at it with their interpretation. There will be mine and theirs. And there are gonna be people who say, 'you need to be doing this about it,' and I'm gonna say, 'I'm doing what I do about it.'