Comics, games and - of course - Watchmen: Dave Gibbons Interview

The legendary artist on crossovers, new projects and why he can't leave Watchmen behind.

Dave Gibbons is famous for drawing Watchmen, perhaps the greatest comic book ever made, but he loves telling stories.

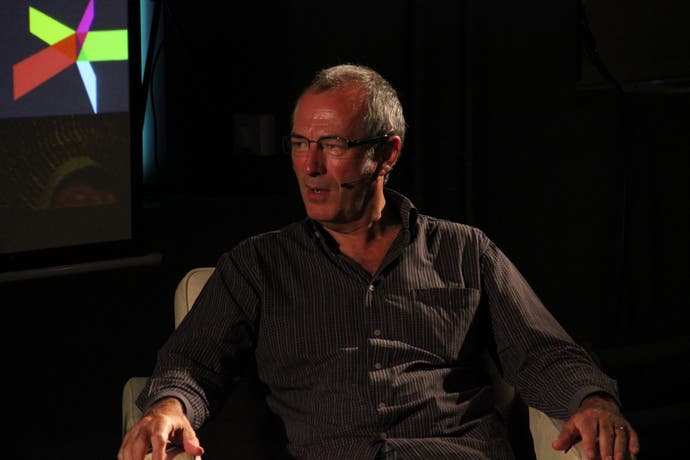

He's sitting on a comfy sofa with a pint in hand, chatting to Traveller's Tales' Jonathan Smith, his son (who is an avid video gamer) and representatives of the GameCity Nottingham festival. In a few minutes he will talk about heroes in comics and video games to a school of would-be game developers and a gaggle of the curious. But for now, he's happy telling stories to the handful around him.

He recounts the time when, in the mid-nineties, having worked with Revolution Software on cult point and click adventure Beneath a Steel Sky, he was taken on a trip to Future Publishing in Bath to pimp the game. The publicist was delighted to discover the journalists had assembled in anticipation of Gibbons' arrival. Then, he worked his magic - he remembers how the hack pack were hanging on his every word as he signed copies of the book and told stories about Watchmen.

So impressed was the publicist that she booked Gibbons to do a Beneath a Steel Sky signing in a London, convinced his popularity as co-creator of Watchmen would guarantee an army of baying fans. Gibbons sat waiting, patiently, pen in hand, a Beneath a Steel Sky sign behind him, a table in front of him.

No one came. Time passed. The publicist made up an excuse to leave and bailed, so embarrassed was she by what was happening. Eventually, a German man came up to him and asked him what he was doing. "I'm signing copies of Beneath a Steel Sky," he explained. "Ah," he replied. "I'll take one."

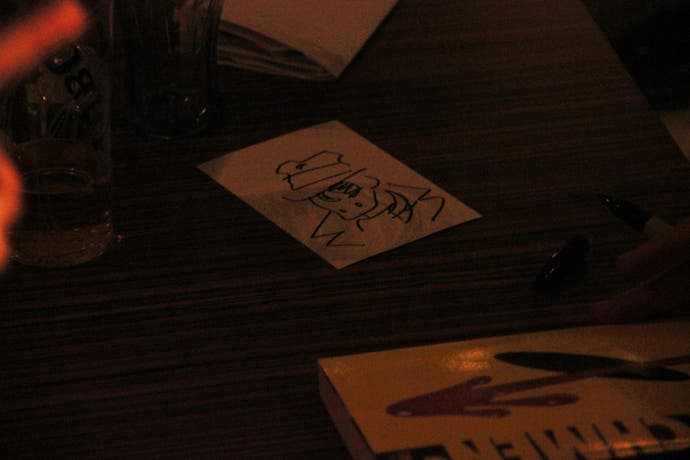

Half a pint down. A GameCity helper tells him he's got five minutes till show time. A publicist asks him to sign a copy of the Watchmen graphic novel. He obliges, opening the book and inking a sketch of Rorschach - complete with trenchcoat and white mask. The ink flows from Gibbons' marker with all the effortlessness you'd expect of someone who has drawn the same picture thousands of times. There's even room for that smiley face. It suddenly dawns on me: this is Dave Gibbons, the man who drew Watchmen, the man who drew Rorschach, probably my favourite comic book character of all time, who drew the iconic smiley face, who drew the alternate New York that stole the show. His disarming London twang - helped along with a dash of US optimism - suddenly has an edge to it.

To me anything to do with the movies - as far as I'm concerned, what Alan and I did was the Watchmen graphic novel and a couple of illustrations that came out at the same time. Everything else - the movie, the game, the prequels - are really not canon. They're subsidiary. They're not really Watchmen. They're just something different.

Gibbons has always kept one eye on the video game world as he's busied himself in comic book land. After working on Beneath a Steel Sky he once again teamed up with Revolution founder Charles Cecil, this time for the re-release of Broken Sword. He consulted on the Watchmen video game (there's a story coming about that later). And he looks set to return to video games at some point in the future, again with Charles Cecil, on an original adventure that will, in his own words, "look like a Dave Gibbons game".

Even though most of his time is spent working on comics (right now, that's in his dining room - he's having his garage converted into a "custom made artistic space") he's perfectly aware of the new moves in the video game industry, and is surprisingly knowledgeable about trends and fads. Perhaps that's why his latest venture is a new type of comic book that shares more in common with video games than any before it.

MadeFire is a digital comic book app for the iPad that lets readers do much more than read. Using specially crafted comic books, you can pause the action, move about a scene by dragging on the touchscreen, view it from different angles and find out more information through footnotes and discover links between stories and scenes buried within the narrative. You can, if you wish, stand in one place and watch a whole panorama revolve around you. You can control the speed at which you read the book. You can go back and look at things again from a different angle.

For MadeFire Gibbons created a comic book - a test to "work out what the grammar is" for these motion books, as they've been dubbed. It's called Treatment, an episodic series set in a future world where crime is rampant. The police refuse to enter the world's cities, but there is a TV show, the most popular in the world, called Treatment, which sees ex-special forces and former cops enter cities and execute people. "It's like cops except people live and die in real time," Gibbons says.

"It's in its infancy. When we've been planning this out, there are all kinds of things you can do that amalgamate the feeling of a game, in other words a thing you can play with and affect with the kind of fixed narrative you get in a comic strip.

"But just in the way computer games aren't just games and comics aren't just comics, no doubt a name will come about that it will come known by. I feel we're on the threshold of a way of doing things that has a lot of advantages."

An introduction from Jonathan Smith, applause, and Gibbons is up in a flash, bounding towards the stage. We enjoy a whistle-stop tour of Gibbons' career in comics, taking in his early days working on 2000AD for IPC Comics through to, of course, Watchmen. Talk turns to heroes - what makes a hero? Why do we like heroes? It's all going swell. The audience loves every minute of it and Gibbons loves the audience loving it.

Coming to a close, the microphone darts about for a question and answer session. Smith asks a question of his own: "Did you see the Watchmen video game tying in with the movie?"

"I did."

"Are you willing to speak about it?"

"It was a little bit out of my control, but they actually paid me quite a lot of money to be a consultant on it. I looked at two of the cut scenes and drew over a bit of artwork to show how I would draw it. That's what they paid me… well, I'd be embarrassed to tell you how many thousand dollars for. But I was a distant consultant.

"I didn't have a lot of input in it. To me anything to do with the movies - as far as I'm concerned, what Alan and I did was the Watchmen graphic novel and a couple of illustrations that came out at the same time. Everything else - the movie, the game, the prequels - are really not canon. They're subsidiary. They're not really Watchmen. They're just something different.

"So I was quite happy to say with the video game, yeah, I like that, and I don't like that, and, that's okay, because it wasn't really anything that impinged on what we'd done creatively."

Comics and games have always enjoyed a love hate relationship, to my mind. Games based on superheroes often disappoint (the less said of Superman 64 the better), and games based on movies based on comics are often worse (Watchmen, Iron Man, Captain America, Thor). There are rare exceptions. Rocksteady's superb Batman Arkham Asylum and Batman Arkham City are perhaps the greatest comic book video games ever made. And Starbreeze's The Darkness is a disturbing delight. But as I listen to Gibbons talk about the similarities and differences of the two mediums, I struggle to think of others.

First, the similarities: "Both comics and games deal in narrative, in dramatic situations that are expressed in very visual and physical means, which might imply that it's crude, that it's just two people banging seven bells out of each other. But it's such a primal form of communication and narrative.

"You think of the guys in the caves in France 50,000 years ago, drawing what they wanted to happen on the hunt - they both seem to go back to then.

"As far as a fanbase, the people behind the games are the same as the kind of people who are behind the comics. They've grown up with them, they've got a lot of enthusiasm for them. They've loved the games or comics they've played or read as kids and they want to make their own now.

"In both the industries there's a huge enthusiasm and joy. And I respond well to enthusiasm."

The differences are more obvious: "In comics you read a story. You're a reader rather than a participant. Although what's interesting about comics is, the reader fills in the bits in between the panels, what we call the gutter. So it's not just all laid out for you. You have to imply with your own imagination what happens between here and there. So it's quite an involving form of narrative. You've got to pay attention to it.

Both comics and games deal in narrative, in dramatic situations that are expressed in very visual and physical means, which might imply that it's crude, that it's just two people banging seven bells out of each other. But it's such a primal form of communication and narrative.

"Games are different in that you set the course of the narrative. There's usually a way it has to go, or a way you're drawn to go, but there's more a feeling of being an active participant in it."

I ask Gibbons for his vision of the future of gaming - perhaps an unfair question of a man who admits to seeing gaming only through the eyes of his son. It's not long before he mentions Minecraft, the world-building indie sensation that has made Markus "Notch" Persson a multi-millionaire. Apparently Gibbons was chatting about it with his son on the drive up to Nottingham, and he sees similarities between it and Watchmen - the paranoia-fuelled alternative universe he helped realise.

"Minecraft is really interesting to me in that the environment becomes one of the parts of the drama, that what you do to the environment affects it," he says. "With Watchmen, the world we set up there was as much a character in it, in that how that world was different than the real world, as any of the fictional characters in it.

"Just as we're finding now, if you come up with a compelling enough imaginary world, lots of people will want to play in it or tell stories about it.

"I can almost see world building will become a very important part of entertainment, outside of particular stories or particular gameplay. People who can create compelling worlds might hold the key.

"It's the gaming equivalent of fan fiction. Stories set in the world of Star Trek or Star Wars, that aren't part of the canon."

It's an interesting point. Look at Skyrim, for example. Here we have an expansive fantasy world with more to do than any one person could hope to do, with quests and a story and all the rest of it. But what's best about Skyrim is how the player creates his or her own story within the open world. Organically, things happen. We make mischief. We play within the sandbox. Bethesda created Skyrim, but within it tales of heroism emerge - our own fan fiction. Not bad for a 60-something bloke who doesn't play video games.

Perhaps this is why MadeFire will release its tools to the community so fans can create their own interactive narratives. It's "the idea of building a community that uses these tools just as the major games like Minecraft have this huge interested base who feel they're all involved together in a joint enterprise" Gibbons says.

Gibbons' talk with Smith ends and he's mobbed by fans armed with copies of the Watchmen graphic novel, that striking yellow cover all around. He sits down at a table, marker pen in hand, and signs every copy - that Rorschach doodle, that smiley face, over and over and over again.

I thought Gibbons would be sick of talking about Watchmen by now. It's been nearly 25 years since it released. I know and he knows that nothing he will ever do will top it in terms of commercial success or influence. I know some famous game developers who snort when asked about the games that made their name. But Gibbons is always happy to chat about Doctor Manhattan and Nite Owl and all the other creaky, troubled superheroes he drew.

"You can only keep going on about these things for so long," he tells me. "And I have been going on about Watchmen for a long, long time. As long as people are interested in it, I'll talk about it."

"But I don't want to be the old guy going, 'I did Watchmen you know!'" he says in an old man New York accent, playfully punching my shoulder. "I wouldn't want to be that guy. But I'm quite happy to talk about it.

"I have to say, by now, particularly after the movie, I think every question that could possibly be asked has been asked. It's like, oh yeah, answer number 17b.

"I still sign copies of the book. I still draw little pictures of Rorschach. Watchmen's been great for me, so I wouldn't ever not want to talk about it. I might not want to, but I always will talk about it."