Brenda Romero versus the systems of pain

On making games about oppression and genocide.

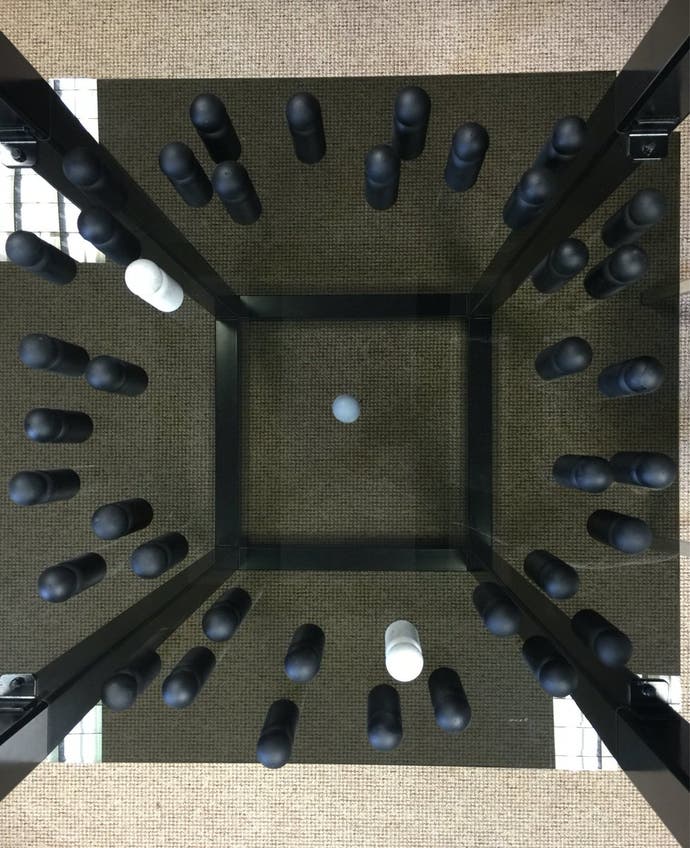

Tucked between shelves at the headquarters of Romero Games, Ltd in Galway, Ireland is a two-by-two-foot cube of black Plexiglass, mounted on a platform and lit from below. I picture it as a miniature of the alien monolith that appears during the prologue to 2001: Space Odyssey, looming over the bustle of a designer's office. This is Black Box, a game conceived by Brenda Romero as part of her board game series, "The Mechanic is the Message", following what she will describe only as an "unbelievably difficult" period in 2006. On top of the cube is a vintage hand-cranked adding machine, from which, when the device is in use, paper spills to the floor. The machine dates back to 1909, but has been extensively cleaned and remade; when Romero first opened it, she was startled to discover her own initials carved on the mechanism within, a moment of eerie closeness with the (presumably, long-dead) manufacturer.

You can see the game's other moving parts inside the cube, and hazard a guess at their purpose. You can also read the numbers produced by the adding machine. But you can't actually play Black Box, because Black Box was designed to be played just once by exactly one person, Romero herself. Completed shortly before I interviewed Romero during her visit to London to receive a BAFTA award in April, it exists now only as a vestige of itself - the rules have been destroyed, the pieces sealed away in defiance of the idea that a game is something to revisit, something to share. "It's the endstate of the game, and it's personal to me," Romero says. "That's how I chose to express that experience. That was a game by me, for me, played by me, and that's just it, really. It's about a horrible thing, and it never needs to be played again."

The projects that make up The Mechanic is the Message represent the pinnacle of a 36 year career in game design, a career that began with an inauspicious job running a tips helpline for now-defunct Sir-Tech, the publisher of the Jagged Alliance and Wizardry games. Romero's better-known credits include Wizardry 8, one of the finest role-playing games of its age, and the rather less fondly regarded Playboy: The Mansion, a title often dug up by those who take issue with her later activism against industry sexism. She is also a prolific academic, the recipient of a Fulbright fellowship, a former designer in residence at the University of California, and current program director for the Msc in Game Design and Development at Limerick University in Ireland.

"I started making games with old board game pieces, and I would flip the boards over and make up my own rules," she tells me over lunch at BAFTA's headquarters near Piccadilly Circus. "And then I got into the industry at 15 and I will die as a game maker - that's all I've ever done. And that is probably the best life you could have. It's had tremendous ups, like this, a BAFTA - a ridiculous up. And it's had its downs - I've publicly failed, I've made some games that sucked! But I've made them and I've released them, and I've learned more from my failures than I've learned from my successes."

Black Box and the other MITM games are born of a set of powerful contradictions. On one level they celebrate how gameplay systems may foster empathy by obliging your participation, involving you as an agent. But they also interrogate how games may echo and help perpetuate the "systems of pain that human beings inflict on one another", the hierarchies of rights and resources that privilege certain types of people while reducing others to non-people, pawns to be shuffled around at the whim of a king or queen. They are public artworks, exhibited in museums and discussed at conferences, but also private, semi-autobiographical creations that spurn easy consumption, made up of rigorously specific rules and materials.

They are, above all, acts of witness which understand that to pay witness in art is to risk a degree of complicity with the mechanisms of suffering. Black Box is "game zero", a designer's working-through of a personal trauma. The others deal more widely with episodes of cruelty and injustice throughout history, but almost all of them view those events through the lens of Romero's own ancestral background and family circumstances.

That mingled love and distrust of systems comes across most forcefully in One Falls For Each Of Us, the fourth game in the MITM series, which investigates the murderous ejection of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole and Cherokee tribes from their homelands in the south-eastern United States during the 1830s and 1840s. Once complete, the game will feature 50,000 figurines, each representing one of the affected Native Americans. The overwhelming abundance of pieces is a challenge to the quietly dehumanising strategies of some games, whereby a single token or icon may stand for hundreds or thousands of people: it sees in such efficient design the implicit destruction of the individual. "When you have 50,000 pieces you want to systematise it - you want to reduce these people to tribes or groups, instead of individuals," says Romero. "Because, if you're going to get rid of 50,000 people, you have to remove their humanity. So I refuse to systematise the creation of them."

More optimistically, Romero's other board games explore how interacting with game systems can bring the experience of oppression home to a player, by thrusting that player into the shoes of either abuser or victim. The first completed game in the series is The New World, which casts you as a slave trafficker ferrying Africans across the Atlantic. Romero designed it on the fly, following a conversation with her part African American daughter, Maezza, who had been learning about the middle passage in school. "She talked about how the ships came down to Africa, and they got the slaves there and took them across the ocean, and they were sold into slavery - but then Lincoln was elected, he passed the Emancipation Proclamation, and they were all let free. And then she asked if she could play a game. And I was just blown away, that this was how she described this - basically, some black people went on a cruise, were stuck for a while and then they got to where they wanted to go."

"And so when she asked if she wanted to play a game, just on the spur of the moment I just handed her these prototype pieces that I had, and I had her paint me some families. She made all these different families, and then when the paint was dry, I grabbed a bunch at random and I put them on a boat which was an index card, and then as they were crossing the ocean she had to roll her die every time, and that consumed food, and she only had so much food, so by the time we got halfway she realises that they're not going to make it. And she asked me what they're going to do.

"So I said, 'well, we can put some people in the water, or we can keep going and hope that we make it, that people won't get sick'. I'm making up the rules in my head - like, how will I handle the sick part. But it was midway through, and then she asked me, 'did this really happen?' This is after a month in school learning about it. She's spent time with these characters, these people that she had made - it meant more to her than abstract representations that she couldn't connect with, I guess. And she started saying things like: 'So if I came out of the woods, Daddy could be gone. Well, if I got to the States, we would all be back together?' No. 'Why not?' Because we're property. I had to explain to her that property didn't have family. This notion of family is gone. So she was tearing up, I was tearing up, it was this really profoundly moving moment for me, not just because she got it, but because it was a game that made that happen. I can tell you what happened, or I can show you what happened, and even if it's unbelievably abstract, you still start to see the systems."

Inspired by her daughter's response, Romero went on to fashion a game about another aspect of her heritage, charting the English dictator Oliver Cromwell's infamously brutal invasion of Ireland across 1649 to 1653. The designer Elizabeth Sampat has written a powerful account of her time with it. Titled Síochán Leat - Gaelic for "peace be with you" - the game is played on a ragged burlap sack which contains family mementos, including a rosary that once belonged to Romero's mother. It represents the invading English as ill-fitting orange blocks, which together spell out the word "mine", and uses small pieces of knitted fabric, one for each county in Ireland as it stands. The rules are written in a mixture of English ink and Irish blood, and the game can only be handled by those with Irish roots.

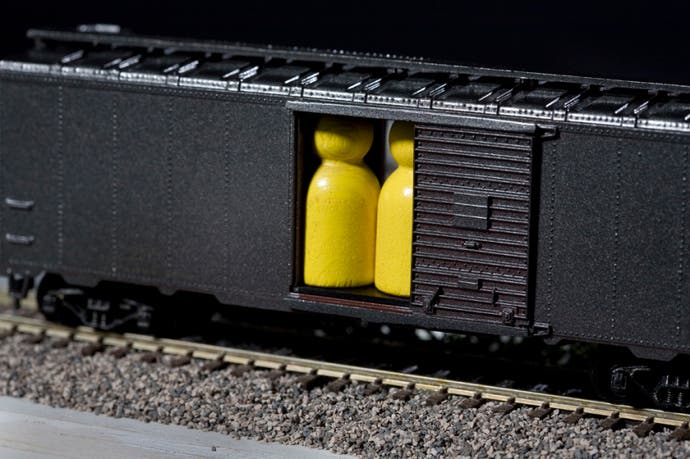

Síochán Leat has been exhibited at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, and had a "transformative" effect on Romero's practice, provoking her to think beyond the conventions amassed during her lengthy spell as a fantasy RPG designer. "It's the coolest thing when you're in a box that you don't even realise you're in, and when you're out of it, it's like, freedom." It was followed by Train, for which Romero is possibly best known today. The latter takes the form of a series of railroad lines, boxcars and yellow pawns, laid out on a broken window pane - during demonstrations, Romero has invited participants to break the glass further before interacting with the pieces. Players take on the role of conductors, loading boxcars with passengers and rolling dice to move them. You can also draw and deploy cards to slow down a competitor's train or accelerate your own.

It's a sparing set of systems, no harder to grasp on paper than Monopoly, but when one car reaches the end of the line, there's a sudden revelation: the trains are actually on their way to Nazi concentration camps. Some critics have dismissed this as a shock tactic, like declaring that all the discarded pieces in a round of chess are murdered children, but the twist itself isn't really the crux of Train. The idea, rather, is to consider the extent to which people are willing to lose themselves in the act of optimising such systems, engaging with their logic, even when they sense the broader implications. The game's theme is hardly invisible, Romero observes - the bleak connotations of loading identical yellow effigies into carriages aside, the broken glass window is a reference to Kristallnacht, the Nazi pogrom against Jewish businesses and residences that preceded the Holocaust. "At some point you're not innocent. At some point you know where these things are going. It's pretty obvious to many people. Like, how is that not even that long ago? What is it, 80 years ago now? That's still not that long ago."

As with The New World, Train came about in part through a consideration of how to explain such events to a child. "When I was making Train I'd spend half-an-hour, 45 minutes, sometimes longer with this image of two children that were affected by the Holocaust. There's this picture of them and they're smiling, and I found that some reports that say they were killed in the Holocaust, and some that say that they weren't. I still imagine the mother trying to straighten their stars, and their hair looks straight, and they're smiling - she's trying to keep their world together. That's a connection I can get, as a mother, trying to keep things happy for your kids when you are just torn apart inside. So I'd spend every morning with those kids, I'd spend at least an hour, at the monitor, thinking about them, thinking about their mother, just trying to internalise something that I could externalise into game mechanics."

Train was the game that propelled Romero's emerging series to public notice. After she discussed her work at the invitation-only Project Horseshoe conference, the designer Steve Meretzky persuaded her to give a talk at a smaller, more open event in North Carolina. Unbeknownst to Romero there was a reporter in the audience, who wrote an article about Train for The Escapist. It created an immediate controversy. "This is 10 years ago now, and [back then] you do not make games about stuff like that," she recalls. "And now everybody knows that I make these games and I don't know what I was thinking, was I going to lose my game developer card?"

There were ferocious reactions online, including a number of threats. But there were also messages of support and interest from designers like David Jaffe, the creator of God of War, and Brian Upton, the designer of Ghost Recon and Rainbow Six. One listener at the North Carolina conference left the venue in tears, only to return and thank Romero for her work. The greatest show of encouragement of all came when Romero was invited to meet a rabbi by a mutual friend. "While I was there the rabbi asked me to bring the game, which was terrifying, and we were there for three hours and he went over every line of the rules, and then at the end he blessed it as a work of Torah. I don't know if you'll ever get a bigger honour than that, right? It was incredible, I was absolutely sobbing."

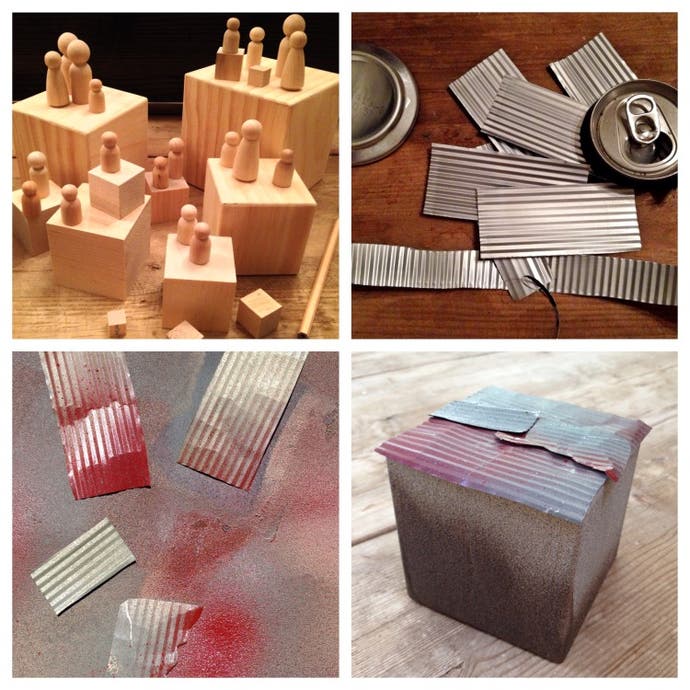

The currently incomplete Cité Soleil deals with a present day injustice, and unlike Train, divides its players into competing groups. It depicts the material and economic texture of life in the slums of Port au Prince in Haiti, with props for shacks that are fashioned from soda cans, their roofs crinkled and daubed purple to resemble weather-beaten corrugated iron. "Everything in the game is built that way - I had a couple of people who were able to get coins from Haiti, so I've got the right economy for the game. The whole game is built out of things that I've found." Among the mechanics are weekly supply truck deliveries, which see dice being upended across the floor like trash from a bin. Any die that rolls an eight or above is a resource, but most of the dice are six-sided. Players are, however, able to lie about what they've collected from the truck. "If you can't feed your kid, if your kid is your last chance at life, are you going to be dishonest? You probably are. You're not just going to say you're out, because you're this close to winning, you're this close to getting out. These systems can produce dishonesty and people would say they'll never do it, until they're placed in this abstracted situation."

Where Train appraises your readiness to play along with a thinly disguised atrocity, Cité Soleil investigates the notion of taking responsibility for those who are indirectly harmed by your decisions, though Romero refrains from going into great detail here. "There are two particular games happening on the same board, at different times, and the players never interact," she says. "And the first time I tested a couple of the mechanics, just to see how they worked, one of the players who was playing during the night killed one of the players who was playing during the day. And I had them paint the character [they'd killed], so that you could show up the next day and see that your character was dead. So their hands were stained with the dye, and there was this really fascinating confrontation between the person whose character had been killed and the person who had killed the character, that happened outside of the game."

The final instalment in the MITM series will be the game currently known as Mexican Kitchen Workers, which portrays how undocumented migrants come to be treated as disposable commodities in many US restaurants. Romero has revised its physical structure and mechanics several times - from using coloured glass beads to symbolise customers and employees, to requiring people to stand in as playing pieces. The project's final form is up in the air right now, following the election of Donald Trump and the resurgence of racism and xenophobic sentiments in US society. "I suspect that whatever it was that was there about the game has gone away like a cloud of smoke. Whatever it was that I knew about the game, it's reshaped, so when I turn my attention toward it I suspect there will be something new there. I've taken Mexican Kitchen Workers through five iterations already."

Romero is personally acquainted with racial prejudice through her marriage to John Romero, DOOM designer and co-founder of Romero Games, who is of Mexican, Yaqui and Cherokee heritage. She and John have also wrestled with the consequences of the US election for their six children. "There's this doll line they have in the States called American Girl, these very fancy dolls, probably over-priced. My daughter has one called Josefina, a little Mexican doll, and she asked: 'if Trump gets into power would they have to stop making Josefina dolls?' And this is not a kid who's glued to CNN, she does not read the New York Times, but somehow that had filtered down to her. And that pissed me off as a parent. And it pissed me off that I had to explain to my 12 year old what a pussy was."

By virtue of its concept, it can be hard to discern the relevance of Black Box to the other games that comprise The Mechanic Is The Message, but the latter's influence is everywhere, like the tug of an unseen body's gravity on visible matter. It's there, above all, in each game's insistence on its own singularity, its refusal to allow the suffering it explores to be replicated and shared. "People would say things like 'well, you can't just make one of a game'. Well, why not? Was Jackson Pollock forced to make 27 copies of Lavender Mist?" Romero would rather players investigate each game's premise independently of the work itself, re-applying her methods on their own terms as they seek systems in darkness, and the darkness in systems.

"Probably once a month suddenly I'll get an email from an educator who will say, I'd like to play a copy or get a copy of the rules. And what I generally encourage the teachers to do is - here's my process, how about you do the same thing with your students, and have them make their own games? Or why don't you tell them about Train, and have them recreate what they think it would be, because part of the process of learning is trying to create those rules. What were the rules that allowed that to happen?"