How Viktor Antonov turned from building cities to planets

City 17 to city infinity.

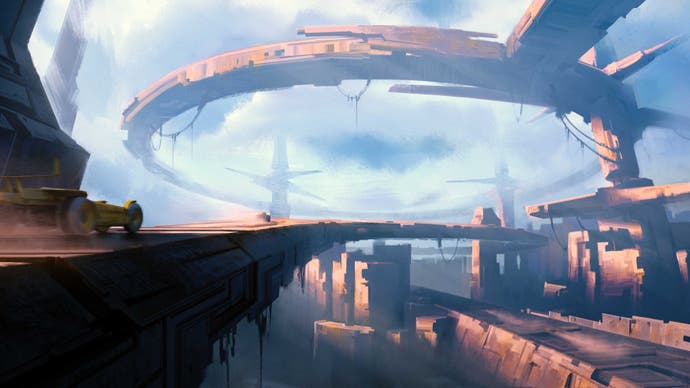

Viktor Antonov hasn't built a world like this before.

The games you know him for are bounded and largely linear. Every tiny detail has been touched by a human hand in Half-Life 2's City 17 or Dishonored's Dunwall, striking virtual places which Antonov has helped colour with particular social histories and inscribed with visual techniques that quietly guide the player to the next checkpoint. That's also true of other games that he's been involved with over the past few years, such as Wolfenstein: The New Order, Prey and Doom, on which Antonov acted as visual design director.

But Project C, as the game is currently codenamed, is very different. "It's one of the most ambitious projects I've worked on and, I have to admit, a fairly difficult one for me," he says.

That's because Project C is set in an entirely open world that operates at the scale of a planet. "The trick for me is, OK, how do I bring my craft from building cities and worlds and chunks of civilisations into a planet? This is the interesting problem I have to solve, to switch from architecture to a natural environment."

Antonov is speaking to me from the Paris studio of developer Darewise. He sits beside large circular windows through which police sirens wail, and behind him is a wall of Kallax shelves loaded with ephemera from Watch Dogs, Assassin's Creed and Ghost Recon, series on which founders Benjamin Charbit and Vincent Marty worked when they were execs at Ubisoft.

Antonov loves Paris. It's the city he and his father first lived in when they escaped from communist Bulgaria, though a few months later he moved to Switzerland and then to Los Angeles to study automotive design. It wasn't until the early '00s that he got to return; by then he'd been working on Half-Life 2 for several years and he thought it was nearly done. But it wasn't, and he ended up having to travel between Paris and Valve's studio in Seattle until it shipped.

The subsequent decade drew him away from the city again, working at Arkane Studios in Lyon and then across several Zenimax studios, so he's happy joining Darewise a couple of years ago has given him the chance to settle again, even if Project C isn't allowing him to imagine and build the kinds of history-layered sci-fi-inflected cities he's used to.

Project C is a fascinating and ambitious MMO built on SpatialOS, the networking technology which allows the creation of richly persistent worlds. This planet's variously perilous flora and fauna will be constantly simulated on SpatialOS' servers, whether there are players to witness them living or not. The promise is it'll add an extra level of richness to exploration, survival, combat and building.

But while it's a kind of game Antonov hasn't made before, he's found it's not quite so alien. "I've always made parallels between nature and architecture because I see a city as a piece of organic growth," he says. He looks at Paris boulevards as rivers, and sees logic in scatters of rocks and scudding clouds: nature is as much a system as urbanity. "It's very obvious when you look into it. You see microorganisms that are very crystal-like and geometrical, and they have repetitive patterns that have functions."

Fittingly, the planet's backstory is it's been transformed by bioengineering. The cities left behind by its previous owners are formed out of organic matter such as trees, and the earth is criss-crossed by patterns of both cultivated and wild growth. Antonov and his team of concept artists have therefore been looking at baobab trees that are used as habitats in Africa, and at tall Yemenese buildings "that grow out of the sand and look like termite habitats. So I'm doing a blend of history and how the first cities were built with how nature grows".

One process he uses to find languages for the shapes of things you'll find on this planet is to take images of micro-organisms and change their scale so they're huge, and also to reduce satellite photos of farmland, quarries and mines in Russia and South America, isolating patterns and transporting them to new contexts.

But though that might make this world sound rather abstract and cold, it has an earthy undertone. The setup is the planet's previous alien owners were tenants, and now it's humanity's turn to rent this planet for a few thousand years and to extract what they can from it.

It's always been important to Antonov to make places that have a strong grounding in real-world politics and culture, and despite the hard sci-fi underpinning Project C, he's finding it in the fact players are pioneers, the planet's first colonisers.

"If the game is in a genre, it would be a frontier story," says Antonov. "It's the grand big adventure of how I'm on this dangerous, beautiful planet which puts me in a place where I have to conquer, master it or die. That takes us very close to the Jack London-like stories of Klondike and gold rushes." And it also edges towards stories of conquistadors in South America, histories of exploitation and violent competition.

For Antonov, these themes heighten the power of the choices the game will give players. "How do I extract the gold? Am I going to be a crook, a murderer or a businessman?" After all, as an open world, Project C gives players lots of different things to do, from farming to raiding, clan-building to exploration.

It's this that really contrasts with the linear shooters Antonov's known for, rewriting some of the rules for world design. "I'm learning that when biomes have a really strong identity and personality, they may not be very accessible because they're too scary or sinister," he says. "I'm trying to fine-tune it so when you're in this world you don't feel like you're in hell, you don't want to escape, you want to stay and conquer it as a promised land. There has to be a constant beauty."

So Project C's biomes are instead defined by what they tell players they can do in them. "Subtlety is not a very useful tool," he says." A desert biome is about giving open space for vehicle combat and exploration, while a city made from a forest of alien trees offers the chance to traverse by grapple and tighter combat, and almost every object is interactive because it's vegetation that grows and can be harvested.

But the first biome players visit has to inspire awe and curiosity. That's the one Antonov knows he has the most control over, the one closest to his previous work, because he knows where players will have come from. And it's the one that has to work to establish the theme and tone he wants. "And then the player moves on and into choosing their role and path."

Right now Project C is at the stage of pre-production when the team builds prototypes and tools that will create the world Antonov and his team have imagined. "This leap of faith between abstract thinking and software, that's where we are now."

Part of the process is to develop procedural generation tools that comprise sets of rules for patterns of vegetation, rivers, rock formations, taking hand-made assets and laying them out naturalistically. It's the first time Antonov has used procedural generation, but he relishes the control he has over it. "Having established these shape languages, the tools become majestic paintbrushes. You can build and throw algorithms and use the right brushes in a loose way and create something you have input as an artist on, but on a huge scale."

He seems excited by the scale of the project and what these tools enable, but it doesn't mean he's turned away from the earthly worlds he's made before. In fact, he'd love to return to a city like City 17. "I'm very interested in continuing to talk about a parallel history and to talk through games and science-fiction, and Europe and future and past and history."

I wonder how he feels about knowing that City 17 is dormant, its history interrupted by the fact Valve never finished the Half-Life series, but for Antonov, it's simply part of a mode of design and imagination that he wants to keep on exploring. "It doesn't have to be Half-Life 3. The way I feel about building specifically urban environments, totalitarian cities, I have my path and I'll eventually do another one," he says.

For now, though, building at the scale of a planet is enough.