How Ghost of a Tale imagines and explores a world of prejudice

Developer Lionel Gallat talks us through an uncommonly smart children's fable.

There are many things I love about Ghost of a Tale, which makes its PS4 debut this week - the ivy bursting through its bulging masonry, the witty and affecting script (with beautifully concise, optional footnotes for those who fancy diving into the lore), or the fact that one of the quests actually has you distinguishing trees by their bark and leaf shape in order to identify the mushrooms growing beneath them. But the biggest compliment I can pay it, perhaps, is that nobody in it feels expendable. The setting may be a prison, an edifice designed to crush the soul and rob the individual of identity, but the story is broadly about reclaiming that identity and finding community in a world of brutal divides. Even the rat guards who chase you around the battlements of Dwindling Heights are people, warts and all, though it's easy to forget this when you're spotted for the umpteenth time exiting a bolthole.

"They're not monsters or demons, intent on killing all the mice - sometimes they don't give a fuck," says Lionel Gallat, the French animator responsible for the majority of a project that has been in development since 2013. "They're just doing their jobs. They're living their lives. And their job is to catch the mouse who escaped from his cell, so that's what they're doing in the game. Until you find the guard armour, put it on and then you can talk to them, and you discover that, no, these are not just enemies you have to kill or avoid. You can talk to them, and you have to talk to them to learn about stuff."

Among the things you'll learn, as the aforesaid mouse runaway Tilo, is that the guards don't want to be here either. They're the dregs of the rat army, incompetents and misfits banished to a neglected fortress to babysit a sad little crowd of thieves, pirates and political agitators. In the course of this handsome 20 hour adventure your relationship with them slowly evolves, from fear through irritation to a sense of tentative camaraderie. It's one of the many splendours of a storybook realm whose personalities, society and history are as cleverly wrought as its cobwebbed undervaults and turrets. "When the game starts, all the characters you meet have led lives, they come from somewhere," Gallat continues. "It's the same with a movie - you need to have the feeling that this world has been going on for a while. The characters don't suddenly pop up because the story needs them, and you need to believe that they're going somewhere."

Gallat himself comes from the world of animated film, specifically Dreamworks and Universal Pictures: his credits as an animator include Despicable Me, The Prince of Egypt and Flushed Away. He is militant about the distinction between film and videogame narrative techniques, noting that in a game, "you really need the interest to be coming from the player" rather than trying to walk them through a plot. Nonetheless, I feel like Ghost of a Tale's cast owe their warmth, depth and liveliness primarily to cinema. Games remain overly partial to the idea that the people or creatures they represent are disposable, grist for player progression or the spectacle of combat. It would be ludicrous, of course, to suggest that it's immoral to harm or kill works of fiction, and there have been many brilliant games that revel in such carnage. But to categorise whole swathes of your cast as "enemy", deserving only of termination, is to chuck out a lot of narrative complexity upfront, and to sacrifice opportunities for constructive social commentary.

Ghost of a Tale borrows plenty from other games - its meticulously imagined citadel is cut from cloth you might expect to see hanging from the ramparts of Lordran - but it takes as much and more from classic animated children's features. In particular, it is shot through with the spirit of 1980s Don Bluth films like The Secret of NIMH and An American Tail, animal allegories that allow you to "lower your defences", as Gallat notes, and explore your responses to difficult social or historical phenomena. "We are talking about people and things that are real, even though we are talking about mice and rats and frogs. It's about what happens to you in life, and there are funny moments, and there are moments that can be quite moving if you pay attention, and if you have empathy."

Above all, Ghost of a Tale is extraordinarily strong as a vision of entrenched bigotry and oppression. The backstory is defined by an apocalyptic clash between the realm's animal kingdoms and an all-consuming, cosmic entity known as the Green Flame. Unable to prevail over the Flame's undead legions, the mice offered to sell out the other species in return for their survival. The rats, however, fought on and eventually won the day. In the aftermath of the battle, the mice were vilified for their treachery, incorporated into the rat empire and treated as second-class citizens.

The idea of a race cursed forever more by an act of betrayal obviously recalls the stigmatising of Jews by some Christians. "We were very aware that that parallel could be drawn, between the Christians and the Jews," Gallat says. "It's not something where I'd say 'I don't know what you mean?'" The game isn't, however, trying to push an angle on any specific realworld history of discrimination. Rather, it is an exploration of how discrimination works when you descend from the haughty remove of plot, and start thinking about it at the level of everyday interactions.

The enmity between mice and other species textures every aspect of Ghost of a Tale, from its dialogue and backstory documents to questions of interior design. It's there in the way the castle's doors and furniture are too large for Tilo, built as they are to serve the needs of rats (compare and contrast this recent Guardian piece from Caroline Criado-Perez on the prejudice in data-led design towards men as "universal referents"). It's there in the casual slurs that dot throwaway conversations with the guards and other in-mates. And it's there in the game's slightly undercooked exploration of "passing" as a member of another social group, with Tilo able to move about the keep freely providing he doesn't dress like a mouse.

Tilo is an intriguing vehicle for exploring these topics not just because he's a member of the game's original "cursed race", but because he's a minstrel, an oral historian. His songbook, which often serves as a quest mechanic and to which you'll add over the course of the game, is awash with racist or politically charged lyrics - ballads excoriating cowardly mice on the one hand, incendiary ditties about rat "plagues" on the other. His spell of confinement at Dwindling Heights is an opportunity to assess the tools of his own trade, to consider how they create the reality he lives in. It's also an opportunity to think about how even the most well-meaning people are shaped by bias, and to ask what kinds of fellow feeling are possible across the barriers of privilege and prejudice.

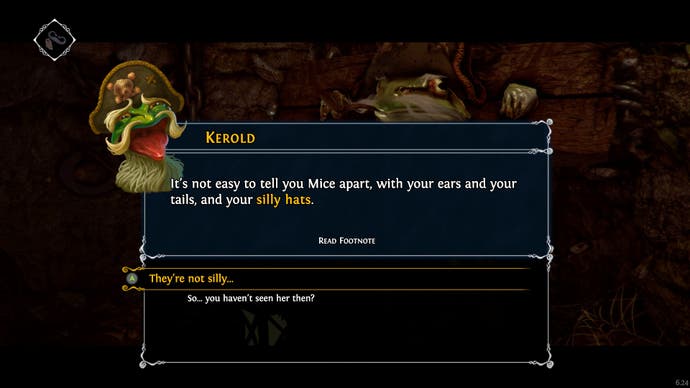

Take the frog pirate, Kerold, who is one of the first characters you meet, chained up in the next cell along. "He's the racist uncle at dinner," Gallat summarises. "I don't think he's a bad guy, but he's very sure of the fact that he doesn't like rodents. He has contempt for them. It's not aggressive or violent, but it's very much what he thinks and he says it, because he feels totally all right with that. But at the same time, he's got this huge admiration for his former captain, he's almost in love with him, and the captain is a rat. It's completely paradoxical. But because of that, I think it becomes credible! It makes sense, because you know people like that in life."