Being the boss of Dragon Age

Mike Laidlaw still remembers his first day at BioWare - and, 15 years later - his last. A lot happened in between.

Mike Laidlaw can still remember his first day at BioWare, even though it was over 15 years ago. He even remembers the date he answered the phone and found out he had got the job: 23rd December 2002. Laidlaw was used to answering the phone; at the time he was working at Bell, Canada's largest telecommunications company, in the province of Ontario. When Laidlaw first joined Bell's call centre, he worked the phones. Later, he got promoted to lead a team on the phones, "which was somehow way worse than being on the phones," Laidlaw told me last March, the day after his star turn at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco. "I went in and said, I'm sorry, I'm quitting. I'm not coming in tomorrow. They said, 'you can't quit two days before Christmas! If you quit you'll never work here again!' I said, 'that is pretty much the plan, yes.' So I walked out, and a bunch of people high-fived me because - yay! - I got out."

We're upstairs at Zero Zero, a pizza and pasta place just a 10-minute walk from the begging mothers and the babies they cradle who sit on the sidewalks that connect the buildings that host GDC, the world's largest gathering of video game developers, a place thousands come to share, to learn, to network, and, occasionally - although I sense through gritted teeth - talk to press people such as me.

Laidlaw is instantly affable, entertaining and interesting. He is willing to talk about things, which might sound like an odd thing to mention, but in this business, it is a rare joy indeed to speak to people who are willing to talk about things. I get why they do not, why developers are hesitant to say too much, because when they do, the fans sometimes come calling - as they have at Mike Laidlaw at points during his career.

He is a confident speaker - I had expected that after studying his performance during his GDC talk on team and project management to a packed audience of video game storytellers - and, clearly, he is well-known within the video game writers circle. Laidlaw's introduction is by a man who sounds very much like a friend, or at least someone he has known for a while. The introduction sounds more like informing the audience an old friend has arrived for dinner, rather than an explanation for why they should listen to him speak.

And Laidlaw is a stickler for detail. He remembers much about his time at BioWare, the fabled role-playing game developer that has been twisted and turned this way and that over the years. He remembers people, what they have said to him, what he learned from them, the mistakes, the regrets and the joy. He will sometimes look to the side and smile, then chuckle as he remembers something important, something that's worth remembering, and then speak of it with the seriousness it deserves. I don't know why, but at points during our lunch I picture dialogue options just at the bottom of my peripheral vision.

At half eight on 3rd February, 2003, a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed 28-year-old Mike Laidlaw walked into BioWare's Edmonton office to join its writing team. There was no-one to greet him. But, he remembers, his new co-workers had already brought in breakfast - a tray with cupcakes and yogurts and fruit and bread. Laidlaw discovered at BioWare, you could make your own breakfast.

Someone walked past and stopped to say hi. "Are you new?" the mystery person asked. "Yeah, I have no idea where I'm supposed to be." It turned out, the mystery helper was Richard Iwaniuk, BioWare's then director of finance. Laidlaw described him as "super easy going" and "the guy who was the hardcore negotiator - I had the greatest bromance with Richard because he was so kind on that first day."

"Do you know what project you're on?" Richard asked.

"No. They didn't tell me."

"Okay, I'm going to guess you're on Jade Empire, so I'm going to show you where the lead designer's office is," Richard said. "I think he's here, but you might want to grab a plate first."

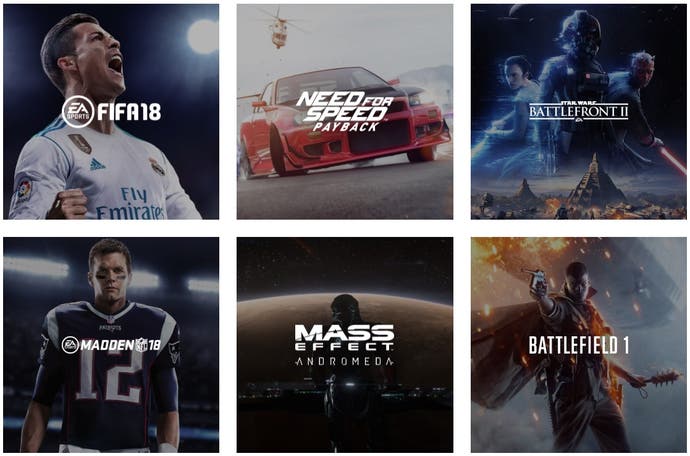

BioWare back in the early 2000s was not the BioWare we imagine now, the BioWare that works for Electronic Arts, the maker of FIFA and Battlefield and Madden and The Sims. Laidlaw's office was in a building in Edmonton's Whyte Avenue, "a really nice college-ey district, but we were overstuffed, let's put it that way." Laidlaw mentions BioWare's HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) more than once. It suffered, he says. There wasn't enough power. He calls BioWare's IT team heroic for the work it did before BioWare moved into its next office. BioWare Edmonton has just moved again.

Laidlaw had a writing background, having gained a BA in English from the University of Western Ontario and a three year stint reviewing video games at a now defunct website called The Adrenaline Vault. Laidlaw expected to work with a writing team on something Dungeons & Dragons related because BioWare had recently released fantasy RPGs Baldur's Gate and Neverwinter Nights. He knew BioWare was making a Star Wars game somewhere - what turned out to be 2003's superb Knights of the Old Republic - and so thought - hoped - he might be put to work on that. D&D or Star Wars, surely. "That's cool, I knew both of those things," Laidlaw thought.

Instead, a copy of Outlaws of the Marsh, considered one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, a stack of kung fu movies and a "giant" design doc were left under his desk. Day one: read this, take those home and watch them, start reading this classic Chinese literature and go! "I was like, okay! That's surprising." Laidlaw had been put to work on Jade Empire, an action role-playing game based on Chinese mythology that came out on the original Xbox in April 2005.

Laidlaw had to build his own desk - a flatpack job from Ikea. He mentions the HVAC again - "it suffered so much it was 35 Celsius in my office, but it was negative 30 outside, so I had to strip down. My boss at the time, [lead designer] Kevin Martins, he looked at me and went, 'so you're a farmer? This should be okay for you.' I'm like, 'yeah, it's like a haymow. I'm good.' He's like, 'cool, well, keep at it and then read the stuff.' I'm like, 'alright, I will do that.' So I built everything up."

Laidlaw was promoted to co-lead writer just a year into the job. He remembers that day well, too. Martins offered him the promotion during a chat on a beach. He needed someone who could focus on interdepartmental organisation. Jade Empire was the first game where BioWare did its own casting and recording for voice over and localisation. Previously, this sort of work was done by the publishers BioWare had worked with, such as Atari and LucasArts. There was a lot to think about, a lot to order, a lot to manage. Laidlaw, it turned out, was pretty good at all of that.

This is the kind of stuff you don't often hear talked about in video game presentations to press, or streams online to players. This is the fiddly stuff, the things that connect the dots, the things that make sure the dots are where they should be in the first place. Laidlaw mentions figuring out pipelines for voice over. "How do we make a script an actor can follow that's coherent? How do we organise our team to be delivering with these new deadlines in mind?" This isn't just cracking the whip - it's working out what a whip looks like, how to make one, and then using it so it gets the job done without leaving too bad a bruise.

I am surprised to learn this about Laidlaw's work at BioWare because I had an image of him in my head as some kind of fantasy loremaster - the kind of person who writes the tomes video game worlds are built from. The kind of person who tells other writers that, actually, I think you'll find that person wouldn't be doing that then because they're off there doing something else.

I was wrong.

"I very quickly realised there were so many good writers and I was never as strong a writer as they were," Laidlaw admits. He mentions Patrick Weekes, a BioWare writer, as someone who "could write novels around me". "But I was always pretty good at organising and wrangling the data around writing and giving you direction and prioritising." This is why Laidlaw was promoted to a co-lead position, or a coordination role. He paints it in terms I might understand: "almost like a really senior editorial role, in a way." This first promotion set Laidlaw along a path that would eventually lead to creative director.

As co-lead, Laidlaw got to do things like negotiate with BioWare's art team and talk to the concept artists. "I made a million mistakes, as you always do," he says. But Laidlaw learnt much about the realities of triple-A video game production during this time, how it works from department to department, person to person, role to role.

Development of Jade Empire was "intensely challenging", Laidlaw says. It was BioWare's first console-exclusive project. It was its first action game. It was its first controller-driven game. It was an all-new intellectual property in an all-new setting. The game's leadership team, which included Jim Bishop, Mark Darrah and Matthew Goldman, had less experience than the leadership team on Star Wars. The crew that worked on Star Wars had worked on Baldur's Gate 2. There was more that was new with Jade Empire, more that was risky. As we speak, Laidlaw touches on the thorny issue of crunch at BioWare. "There were a lot of spinning wheels as we tried to figure out the VO," he says. "There were periods that were pretty intense, like crunching and demos and stuff like that."

Laidlaw, though, remembers some of his time working on Jade Empire fondly. "Highs and lows," he says. It afforded him his first trip to E3, the video game super show where publishers gather to willy-wave their hot new products in front of press, the public and the expectant gaze of investors. Laidlaw worked the Microsoft floor in the BioWare booth, and was thrust into his first on-camera interview because Ray Muzyka, one of the founders of BioWare and for years one of the faces of the company, was busy and thought he'd do a good job.

"I was like, oh my god, okay. Alright!" Laidlaw says, before recounting one of his life philosophies: "when something scares you, you should probably say yes unless you can come up with a very compelling reason not to. That was just, I don't know if I'm good enough, but apparently, Dr Ray thinks I am, so you know what? I'm going to give it a try."

But, ultimately, Jade Empire was "tough". In times of intense crunch, developers often form unlikely partnerships. Friendships fuelled by a desperate camaraderie spark into life. On Jade Empire, Laidlaw found a kindred spirit in a "wonderful, brilliant, if a little acerbic" German technical designer named Georg Zoeller. The lead designer's wife, who had had a baby, had torn tendons in her knee and so he had to spend time out of the office. Mike and Georg "backfilled" for him. "I was the good cop, and my German compatriot was the bad cop," Laidlaw says with a chuckle. "And of course he was the technical guy, whereas I was more like the art and the softer skills."

Perhaps diplomatically, Laidlaw describes the BioWare that built Jade Empire as "not as mature in terms of project management". Scheduling and scope control were not BioWare's strong points. (This, he insists, is something BioWare is actively trying to improve.) All these development problems combined to cause "quite a bit of burnout" at the end of the project. I sense that's putting it lightly.

Jade Empire came out in April 2005 to mixed reviews. Laidlaw says he was proud of the game, its setting and writing, but acknowledged its flaws: the combat "never quite gelled", and the game suffered, he suspects, from expectations set by Knights of the Old Republic, a game that had come out just under two years earlier ("the people who had played Knights of the Old Republic were like, well this is like Knights of the Old Republic but it's not".) Analysis of the production began and it led to the beginning of a commitment to try to reduce crunch, Laidlaw says.

Sales were fine, he says, but "not Star Wars good". Jade Empire's primary platform was the original Xbox and the game came out right at the end of its life. Its release date had been delayed enough that the Xbox 360 was announced just a month after Jade Empire launched, and sales tanked on all original Xbox exclusives. "That was unfortunate," Laidlaw says. "If I could go back with a time machine I'd be like, no no no, there's so much we have to change. But that's life. Hindsight's like that."

After a vacation to combat the burnout (BioWare, Laidlaw says, was always good about giving staff on-the-house vacation days to make up for some of the overtime spent during crunch periods), Laidlaw worked on Mass Effect, the company's big new space shooter RPG. Laidlaw worked with Drew Karpyshyn, BioWare's celebrated writer, for a time. "Drew will tell you straight what he thinks you did right and wrong," Laidlaw says with a smile. "He is a very straight shooter. Somewhere between direct and blunt is his communication style depending on the day, and that's okay."

Karpyshyn gave Laidlaw an opportunity to write a section of the Citadel, Mass Effect's giant city in space, but it never saw the light of day ("they didn't have the level art budget to build it at all - it was mostly sidequests - I think that was a good call"), and some of Noveria, one of the planets players visit during the adventure (Noveria ended up under the pen of writer Chris L'Etoile).

Laidlaw did, however, work on parts of Mass Effect that made the cut: three alien races who were described as "non majors". This meant they couldn't be like the game's major alien races, such as the turians or the asari. The Mass Effect concept art team gave Laidlaw between 30 and 40 aliens they'd created. Laidlaw picked three, named them and developed their culture. They were the volus, the hanar and - my favourite - the elcor.

As a Mass Effect fan, I get a kick out of picking Laidlaw's brains on the creation of these three alien races. He designed the volus to be the space accountants to the turian military war machine. This is a symbiotic relationship; the volus, who are rotund, wear exo suits and have alien asthma, clearly cannot fight. The hanar came to be because Laidlaw thought it would be nice for Mass Effect to have some degree of spirituality. And then the elcor, the dour alien race who stand on four massive legs and explain what they're about to say. Laidlaw wondered, how do we make them different but coping? He wanted the rest of Mass Effect's galaxy to totally get them. They were never ousted or treated like an ostracised sub-race - that's just how they talk. "I'm a Star Trek guy," Laidlaw reveals with some courage. "I love Star Wars, too. But I grew up on Star Trek. And that inclusive future is really exciting. So I was like, let's go with that. I got my oar in." I mention the elcor reminded me of Eeyore from Winnie-the-Pooh. Laidlaw counters: "except their only emotion wasn't depression. They had more going on. But yes, the delivery was absolutely Eeyore."

Laidlaw worked on Mass Effect for six months before he was put to work on the sequel to Jade Empire - a game that never came out. "We don't really talk about it in too much detail, but there was one," Laidlaw says. Laidlaw joined forces with Mark Darrah, now executive producer of the Dragon Age franchise. The pair, as part of a small team, spent over a year working on Jade Empire 2 as more of a prototype project while the majority of the studio focused on Mass Effect. It had real potential he says, but the art direction was a stumbling block.

Jade Empire 2 was in the process of being shut down when Laidlaw was asked whether he'd be interested in working on Dragon Age. At this point, the core of the fantasy RPG had been designed, but the team needed someone to steer it from where it was to a place where it might get a sequel, where it might end up as a franchise. Laidlaw was told his writing background would help. That life philosophy he mentioned earlier pops up again - it was another "scary moment", and so Laidlaw said yes and moved onto the team. When he arrived he found a design that had been "brilliantly done", but there was much work left to do and a lot of bugs to prioritise, a process developers call "triage". Dragon Age needed medical attention, and Laidlaw was the first aid kit.

Georg Zoeller, the German technical designer Laidlaw had become friends with during his time on Jade Empire, walked into Laidlaw's office and said, "if you're the lead designer, we have a problem." Zoeller had a question about status effect visual effects: how would the game display them when someone has six buffs on them? This question, and many others like it, were Laidlaw's problem now. Laidlaw's solution, by the way, was to create a prioritisation system that worked out how important each status effect was and displayed it accordingly. ("How important is it that I know right now that I have plus one to strength? Probably low. How important is it that I know I'm on fire? Probably very high.") The first three status effects, ranked by priority, would be the ones that would display above a character's head. "The programmer and the designer were like, okay, yeah, that works! That was hour two."

Mike Laidlaw is not the Dragon Age "visionaire", despite having worked on the franchise for a decade and, eventually, becoming its chief creative. Laidlaw credits writer Dave Gaider with building the game's history and lore. As the studio moved into working on Dragon Age sequels, more people became involved. For example, Ben Gelinas, a former crime reporter BioWare hired from its local newspaper, the Edmonton Journal, became the Dragon Age lore curator after Dragon Age 2. Gelinas, who had a good eye for detail, spent six months digging through all of the Dragon Age games to look for lore mismatches. He built a wiki that contained not only information that was publicly available but information privately known, retained for the future, "secret knowledge", as Laidlaw puts it.

Laidlaw worked on Dragon Age Origins for around three years. The game had been delayed in order for BioWare to "sim ship" - release it worldwide on PC as well as on consoles (an Austin-based developer called Edge of Reality helped port Origins to PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360). Laidlaw says this was a wise decision, as it meant Dragon Age came out in one big burst, got people's attention and it was probably available on a platform they had access to. The game's entire design team reported into Laidlaw, so he was he first point of triage for all the bugs that came in. This job was another that involved prioritising things. For example, a bug report might revolve around a line of dialogue that didn't quite make sense. Laidlaw would have to accept that nothing could be done, "because it's a bit of a feel thing and I'm not going to spend $2000 for a full session for an actor to re-record one line."

If a bug came in that was mission critical, Laidlaw would work with the game's designers and "facilitate communication" to get it sorted. Perhaps art could help, or programming. His job involved a fair amount of shepherding to get things done. Laidlaw says he was "a cross-disciplinary problem solver". "Your job is to advocate for the design team to advocate for the player and say, we want this to be a great experience. We understand some things are impossible, but what about the improbable? What can we do there?"

But, like Jade Empire, Dragon Age was fraught with challenges. In the early stages of development, Origins wandered in terms of vision. (It wasn't until Origins director Dan Tudge called Dragon Age the spiritual successor to Baldur's Gate and told the team to aim for that vision, that momentum began to build internally.) The Origins part of Dragon Age caused problems, too. One of the fantastic features of the first Dragon Age is not only did it let you pick a race for your character, but depending on that choice you got one of six different origin stories. But this fantastic feature caused the developers a headache. There was a huge amount of work involved to create these origin stories, which doubled as tutorials and introductions to the world of Dragon Age. Each had to establish the core crisis of the world, the threat, the protagonist and antagonist and ground the player in their role. Oh, and each had to teach the player how to play the game, introducing combat mechanics and navigation comprehensively enough that the player would understand how to play Dragon Age by their end. With six different openings, you have to solve all of those problems six times when most games do it just once. For each, the developers had to work out things such as where to teach the player to attack and where to teach the player how to control their party. "Oh god!" Laidlaw yelps at the memory. It's no surprise BioWare moved away from the origins structure for the Dragon Age sequels.

At this point, with Dragon Age's tutorial fresh in his mind, Laidlaw brings up The Witcher - CD Project's rival fantasy RPG. Dragon Age and The Witcher are often compared, as are BioWare and CD Project. This is not an entirely flattering comparison for BioWare. Where criticisms exist for the Dragon Age games, The Witcher series is revered. The Witcher 3 in particular is held up on a pedestal, its place in the pantheon of the RPG immortals already secured. Dragon Age though, well, Dragon Age is complicated.

"Everybody asks me about The Witcher, like I'm going to be angry at The Witcher 3," Laidlaw says, ripping the plaster off. "I'm like, it's an amazing game. Why would I be upset? I don't even know how it ends! That's so cool, right?"

Laidlaw proceeds to praise The Witcher 3 and - jumping forward - compares it to the third Dragon Age game, Inquisition. The Witcher 3's side quests and pacing "were better than Inquisition's", he says, but more importantly, he stresses, White Orchard, the first playable area in The Witcher 3 beyond the tutorial, was "crisp and perfect" in terms of introducing the player to the major themes of the game and the role you played in the world. "They did it by hooking you with nice cinematics," Laidlaw says, "they did it by introducing a cool griffin fight. But they also backed it up with Vesemir being there. He disappears after that, but Vesemir's there to give voice to anything you might be confused about. Geralt, you know this! Ha ha ha! And you're like, oh, clever! Clever!

"It's always nice to have a microcosm of the game world. You also see this in Horizon Zero Dawn, with the Mother's Heart. That opening zone is a microcosm of the larger game. But with The Witcher, the narrative hooks are actually stronger. The whole, I need to find Yennefer, and I have that opening flashback where, clearly, we're in love, and Ciri is also adorable and kind of a little bratt, it's like, okay, wow, those hooks are set really early, and then it's made clear that is going to be continued.

"I think Witcher 3 is one of the best openings in games. I don't see a lot of people dig in on that. For me, that's the template for how to do it exceptionally well."

I'm not surprised Laidlaw knows The Witcher 3 so well (most developers play "the competition", despite often refusing to mention them by name in interviews with the press). I'm more pleased he has dug into the game and has interesting thoughts about it.

"People like to overplay the idea development studios are hostile or antagonistic to one another," he says. "Like, that somewhere I have a Skyrim shrine because how dare they create a great game? No! I love Skyrim. I'm the guy who followed the Skyrim Revisited mod pack. It literally took me three nights to install 175 mods. There was a mod where I put level of detail models for trees into the game, and then ran a fan-made processor that made the level of details for those models and integrated them into the game. My Skyrim is amazing. I love it. It's a great game. And it's worth putting that kind of time in just to see how far the mod community can take it.

"I don't know how those games end! I know how my games end. I can't play my game after it comes out. If I can, it's after two to three years. But Witcher I can fire up and be like, awesome, cool, I'm Geralt, I don't have to worry about a party, it's an action-based combat system, it's in a completely unique world. Cool! I love this! I don't know this! I don't know what happens! Hook me up!

"I didn't get into RPGs because I hate RPGs so much, right?"

BioWare was confident in Dragon Age Origins at launch and its reception was better than Laidlaw expected. The response to the console versions was "a bit more tepid" than that of the PC version, but the sentiment BioWare saw was, well, it's a bit janky but it's worth it. Lots of people were excited to see the return of an old-school top down RPG (via the tactical camera on the PC version), with choice and consequence that could play out in a deep way. I know because I was one of them.

And then Dragon Age 2 came out.

BioWare rolled onto Dragon Age 2 midway through development of Awakening, the big expansion pack for Origins. BioWare needed to release a project by a certain date. This was presented to the development team as a challenge or an opportunity. This was not a development timeline that would allow for the follow-up to Origins deserved.

Knowing the time crunch the team faced, Laidlaw drew inspiration from Silicon Knights' beloved Eternal Darkness, in particular the section where you played a Cambodian court dancer in the brightly lit temple, and then, 833 in-game years later, played an archaeologist who explores the same temple, now dark and full of cobwebs. Laidlaw's idea was to reuse spaces in a similar way. Similarly, Dragon Age's areas would evolve over time and wouldn't have to be completely redone or remade. BioWare thought that was the only way it could work through the brutal crunch it faced, and so built a 10-year story as a way of "leaning into the corner, as they call it".

BioWare had between 14 and 16 months to build Dragon Age 2, from concept to the game appearing on shop shelves. This was a game with half a million words of dialogue. "It's impossible," Laidlaw says. "I tell other people that and they kind of get all blanched and go, oh my god, are you okay?"

Laidlaw was not okay. He suffered on both a physical and emotional level. I ask him how the brutal crunch affected him personally.

"You name it," he replies. "Sleepless nights. Insomnia. That kind of stuff happens."

What does it feel like, when you're trying to build a game under those conditions?

"You get a bit of - it's not hyper-focus - you lose a lot of objectivity. It's hard to stay that course. It's exceptionally hard to lead a team and know you're asking a very challenging thing of them."

BioWare gave Dragon Age 2 its best shot, but the problems with the game were many: reused assets for dungeons, a small game world and a simplification of combat that did not go down well with BioWare's hardcore fans.

How does Laidlaw feel about Dragon Age 2 now, seven years after it came out?

"I carry a fair amount of guilt around Dragon Age 2," he replies. "You always feel in retrospect there were decisions you could have made that would have been better. You carry that around. You can either be broken by it, or use it as fuel to do better. I'd much rather use the latter. If I get a team health survey that says Mike Laidlaw is terrible and doesn't know how to run the team, that feels terrible. That happened a couple of times. But, mostly, you want to use that as a catalyst to never have that happen again.

"We tried very hard to control the scope. But in hindsight, I know I could have done better. If me, now, 2018 Mike Laidlaw went back to Dragon Age 2, there are many things I would do in terms of evaluating scope and building better crumple plans. A lot of that stuff I learned through not getting it right.

"We took our best shot and tackled it. The quality that came out for Dragon Age 2 is something I'm intensely proud of. Not because it's, ah, that's even better than Origins. I recognise it's not as good as Origins. But it is a game with a ton of heart. It took a lot of risks. It told a very different story. And a lot of people will come up to me and be like, I don't know why people disliked it, that's my favourite because it was so different."

Reeling from the most brutal crunch of his career, Laidlaw then suffered the full force of fan feedback. Dragon Age 2 was a faster-paced game than Origins and was designed with a console and a PC interface in mind from the start - a mandate from upon high. BioWare's core fanbase took the changes personally. "You built us a game that made us think of Baldur's Gate and then you took that away," Laidlaw says, remembering the time.

Some singled out Laidlaw, saying he was responsible for everything that was wrong with Dragon Age 2. Some accused Laidlaw of hating BioWare fans. "You want the game to sell on consoles to people who are dumb, which I think is a really fucking unfair thing to say. But a lot of the attacks were very personal and very intensely: you should be fired, you ruined Dragon Age."

BioWare received a lot of these kinds of messages. Some were hand-written letters. Some complaints made their way through customer service. Social media was at this point on its way. Developers were all of a sudden more available than ever before - and an easy target for fan vitriol.

Laidlaw says he'd rather take all the hate and personal attacks on the chin than see "literally anyone on the design team" go through it. "I will happily take that blame," he says. And, despite this, he still believes publishers should push individual developers to put themselves out there, to show there are very real faces behind the games they love. "People tend to respond better when they're like, oh, okay, there are people who made this. It's not just a thing that rolled off an assembly line... The fact I said yes to that interview Ray couldn't do on Jade Empire is partly why you know my name.

"But I also feel if there's going to be blame, whoever is wearing the crown, if someone is getting credited, Mike Laidlaw designed this thing, then they absolutely need to be able to stand up there and say, you know what, it wasn't perfect, and that's okay. If you want to yell at me, that's alright. Because if the team isn't getting the credit, they absolutely don't deserve the shit. It's quite the opposite. They deserve all of the credit and none of the shit."

I ask Laidlaw whether he has a thick skin. "No I don't. Not at all," he replies. "I feel it every time. And it hurts. But! I am centred enough to know I did not go out and wreck that thing. I did not destroy that thing. There was no malice in my heart. If anyone was in there fighting for tac-cam, it was me. But, what I recognise is it's really important you stand up for the accolades and the bullshit. Because many games will have both.

"Speaking about the game and being able to do PR has a responsibility, because I know it's got another edge to it. Not everybody should have to deal with that. That's all. The team needs to see that. They need to see I'm not throwing them under the bus, right? They don't want that. I should know."

After the negative reception to Dragon Age 2, BioWare wanted to address specific concerns through downloadable content. In this the company was relatively successful, and, Laidlaw suggests, the feeling on Dragon Age 2 has "mellowed out" over the years. "The DLCs restored some degree of faith," he says. "I did see in Inquisition's early run people going, 'well, if it's more like what they did in the DLCs for DA2, I could get behind that.' That was our hope."

Laidlaw says the Dragon Age development team was ready to build a new game in the series, despite what it had gone through getting Dragon Age 2 out of the door. "The studio felt in no way the franchise was dead." The other option was to reinvigorate Jade Empire, "which certainly could have happened." But Dragon Age had more "pull" and "awareness" than Jade Empire, Laidlaw says, not just in terms of sales but knowledge and understanding. Or, BioWare could try and build a new intellectual property, which would have been an enormous undertaking. "So, the thought was, let's keep going and build a third."

The discussion revolved around which engine BioWare should use to build the game. Should it stick with the Eclipse engine, the one that had been used to build the previous Dragon Age games, or should it move to another engine? The decision was made to move to another engine, and that engine would be Frostbite, the engine created by Battlefield developer DICE and now used by pretty much every internal EA development studio to build games.

Dragon Age benefited from Frostbite in many ways, mostly to do with the graphics. Visual quality went up alongside rendering capability and capacity. But the engine had not been built with role-playing mechanics in mind, such as save anywhere. Battlefield games were built with checkpoints in mind, so the tech to underpin a role-playing game such as Dragon Age simply wasn't there. Frostbite had never done custom characters or even quadrupeds such as horses. BioWare ran up against challenge after challenge building the tech that would help Frostbite build Dragon Age 3.

Laidlaw's role as creative director involved meeting with the various teams put into place to build Dragon Age 3 and ask questions, to figure out the wheres and the hows. Occasionally, he would suggest ideas. One was the warrior class' guard mechanic. Here, warriors could build false hitpoints - temporary hitpoints, essentially - that needed to be whittled down before a warrior's true hitpoints were affected. Laidlaw says the guard mechanic was a response to the game feeling like it had an overreliance on healers. Because mages were the only class that could heal, Laidlaw felt the game was forcing the player to have a mage in their party in order to create an effective playstyle.

So, Laidlaw pushed for the guard mechanic. It meant most of the warrior's tanking maneuvers, such as taunt or guarding or parrying, would generate guard. Not only were you stopping damage or pulling it away from other characters in your party, you were giving yourself the capacity to take more punishment.

"That was the one where the combat team went a little cross-eyed and said, are you sure?" Laidlaw laughs. "I went, I think it will work. I think it was relatively successful. It was kind of new. Not that temporary hit points are the craziest thing, but still, I think it added something to the game that had a purpose behind it, which again was, if we're driven by character, let's make it so any party could be valid.

"On nightmare, like playing on the highest difficulty level, sure, maybe not every party is valid. But if you're playing on normal I want you to be able to enjoy Bull, Blackwall and Cassandra with your rogue or something. That would be cool. Let's try that.

"It's not, do this Bob. That's me at my worst. Me at my next worst is casually mention a thing and not realise when people took that as a mandate. That may actually be even worse - the accidental directive. Whoops! Sorry, I didn't actually mean you had to. Well, we thought you did. Damn. Bad communication."

One of the more interesting aspects of Dragon Age Inquisition had to do with its structure. The game employed a hub and spoke design that meant you could select a destination from a world map - represented by a map on a war table in your castle base - and fast travel to them. Some of these destinations were massive, mini open worlds in a sense. Dragon Age Inquisition did not follow the lead of other popular RPGs of the time, such as Bethesda's Skyrim, by presenting the player with a single, enormous open world to explore right from the off. Inquisition went for a more tailored, directed experience similar to that seen in Mass Effect.

There were a few reasons for this, Laidlaw explains. It meant BioWare could hit the player with plot evolution moments when they returned to base after a main quest mission was completed out in the field. "We could push you to re-engage with the critical path at times because of the travel nature of it, as opposed to, well, I've been over there in the west for, like, in Skyrim - and this is not a critique because this is honestly Skyrim's value proposition to the player - you can do whatever you want and I love it, but it's possible to play and never get the shouts," Laidlaw says. "Whereas what we were able to do by having you go back to Skyhold or Haven is unlock and expand the world, so we were like, okay, at some point you need to re-engage with story because the open-world content will dry up. You're sitting on this bulk of power, which was an unlock mechanic, go tackle one of the story beats."

Whenever the comparison between Dragon Age and Skyrim comes up, Laidlaw reminds people Dragon Age has hours of cinematic, scripted, "hand-touched" linear content", which Skyrim does not. He compares Dragon Age to BioWare's other game, Mass Effect, where you landed on a planet and did, say, Miranda's loyalty mission. You have a base, start there, go through the planet and when you're done, return to your ship.

The other reason for Inquisition's structure was a desire to address the criticism that Dragon Age 2 lacked variety and was set in the same city throughout the game. Laidlaw says the development team had a mandate to be more open world "from studio leadership and EA". "We said, it's not going to be easy, but it's also not going to be impossible for us to have a scenario that is say, different from Skyrim, where Skyrim tended to be somewhere between alpine hot springs to holy crap it's snow everywhere. We were able to go, jungle to swamp to mountains to desert, because you were moving geographically.

"Building biomes that connect from hot springs mountain to desert is, well, it's not impossible, it's just exceptionally challenging. We wanted to play up visual variety and find something that made us different from the style of Skyrim at the time, and to stand out and say, every once in a while, you come to a snow area that's absolutely infested with red lyrium, and you almost fight through it like you're clearing base after base, right? That was a more linear open world level. It was an opportunity for us to demonstrate variety, to showcase new spaces and to give the player a break from the visual fatigue of seeing the same thing over and over again."

Inquisition, most who played it agree, had a pacing problem. The open worlds simply didn't offer a huge amount to do, save meaningless collectathons and puzzles visualised by scores of icons dotted on each map. "We recognised it was a little hollow," Laidlaw admits. But BioWare didn't have the game's open world up and running in a realistically playable way early enough in development for the team to change course.

Laidlaw says if he could go back and make Inquisition again, he would take influence from The Witcher 3. "I love the way The Witcher 3 put more cinematic, more heavy story quests into those open worlds in order to even out the pacing and do it in a way players responded to super positively," he says.

"Whereas in our case, it felt like there were two phases of the game: there was the stuff in the open world which, again, the writers did a great job of theming each zone so it had like, oh, this is the one where there was an expedition that went missing and it's all full of notes, but it was never quite the same as the level of intensity you got when you went back in time and rescued Leliana from Redcliffe. Those were heavily cinematic. So, I think it was a bit jarring due to being inconsistent.

"If I could go back I'm sure we'd look closer to The Witcher 3 - in the hindsight that I've seen The Witcher 3. Even we knew it was living where it was and we hadn't balanced our budget in our deployment of stuff properly in the same way hindsight would have led me to do."

BioWare spent around four years building Dragon Age Inquisition. A large part of this time was spent dealing with the engine changeover. A significant amount of engineering had to be done to stand up Dragon Age's conversation systems, its ability to do stats and levels, what Laidlaw calls "the RPG guts".

The development team experienced the dreaded crunch, but it was different to the crunch it suffered with Dragon Age 2. Where Dragon Age 2 was an exceptionally hard push followed by a "how dare you?!" recrimination, Inquisition was "a long, steady push".

"It wasn't a breeze by any means and people worked very hard," Laidlaw says, "but it came out and people went, wow, okay, that's good.

"We were better, but there was still enough for it to be a fail in my book," Laidlaw adds, while pointing to a personal failure that he didn't create a cohesive experience the design team was able to understand and dig into. "That was a challenge," he says with a sigh. "I don't feel like it was the worst thing ever, but there are always things you could do so, so much better to make sure your team understands the vision and the purpose behind what you're doing, that this is a significant and necessary part of the game."

The upshot of this is Dragon Age Inquisition's development meandered, creating disillusionment. Staff worried content would be cut, and development did not feel as tight or as driven as it could have. "These are things you learn about managing a 50 plus person design team amid a 200 plus person overall gameplay team."

Some content - some significant content - was cut, and players noticed. Features shown of in a high-profile PAX Prime demo of the game in September 2013, such as impressive environmental interaction and keep capturing, did not make it into the final game. This PAX demo, fronted by Laidlaw and Mark Darrah, also included features such as burning boats to prevent your enemies from escaping and an Inquisition Keep Strength bar that acted as a visual representation of your keep's defence against enemy attacks. None of this made it into the game that shipped in November 2014.

"I feel very bad about that PAX demo that had some features we eventually had to cut," Laidlaw tells me. "I feel very bad about that... That's the reality of development. It's certainly the reality of, oops, you're on five platforms and two of them are significantly older than the other three. There were some really good ideas in there and I wanted to see them, but at the same time they were not fleshed out and proven enough."

Now, Laidlaw, like so many developers in the post No Man's Sky world, has a new marketing mantra: promise less in the run up to the release of games. We're in a show not tell world. We've seen it with Rare's promotion of Sea of Thieves and short marketing campaigns from big publishers. "I look at it and go, these days, my ideal marketing line would be three days before the game comes out, run a demo that's actually a final code and go, 'okay everybody, that was our video game, I hope you like it, it's available for sale soon.' And then I sit down and go the hell away. Perhaps not the most practical PR! But still, it's real honest."

After the release of Inquisition, DLC followed. BioWare Austin, the studio responsible for MMO Star Wars The Old Republic, had a team working on a game called Shadow Realms, which was eventually cancelled. The bulk of that team moved over to work with the Dragon Age team on The Descent, a dungeon-focused DLC for Inquisition. This happened while the bulk of the Inquisition team worked on Jaws of Hakkon, Inquisition's first DLC.

Jaws of Hakkon takes place entirely in the Inquisition open world, with cinematics and story moments. The exploration feels more integrated into the world than anything in the vanilla game. "Jaws of Hakkon was us attempting - just like DA2 - to say, okay, if we needed to reintegrate story back into an open world, what would that look like?" Laidlaw says.

After Jaws of Hakkon, BioWare set to work on Trespasser, Inquisition's third and last DLC. Fans tore through Trespasser on the hunt for clues that would point to the next Dragon Age game. They found those clues. Trespasser, it turned out, pointed quite clearly in the direction of the next planned Dragon Age game, not just in terms of story, but setting. "It put up a flag that said we might be going this way, y'all," Laidlaw says. "It made some very clear statements about what might be next."

Trespasser, which came out in September 2015, enjoyed positive reviews and did exceptionally well for BioWare. Fans expected Laidlaw and BioWare to roll naturally and seamlessly onto Dragon Age 4. But two years later, he announced he had left the company he joined 14 years earlier.

Mike Laidlaw choked up during his goodbye speech to the BioWare team. BioWare's senior editor Karen Weekes walked into his office as he was packing up his things and said, "I don't know if this is weird, but the designers have accidentally thrown you a wake over there at the bar, and I don't know if you'd want to come, but I think a lot of people would be really happy if you did." Laidlaw asked if there was booze. There was a lot of booze.

It was time to leave, Laidlaw says, after 14 years at BioWare ("14 years is the seven year itch times two - it gets real itchy!"). Laidlaw, convinced the next Dragon Age would have been his last one in any case, had seen a large part of his team move over to Anthem, BioWare's big new IP and perhaps the company's biggest bet in years. Laidlaw calls this "not a surprising development". "The team I had was shrinking so drastically it was going to be quite a while before we ramped back up."

Laidlaw also felt he was leaving Dragon Age in good hands. Mark Darrah remained, as did art director Matt Goldman and technical director Jacques Lebrun. It was about being as non-disruptive as possible. The next Dragon Age had yet to be announced, although its existence was an open secret at this point. "And while I'm a little scared and I don't know if I'm ready, I feel like being responsible as a leader means not ditching out in the middle of something," he says. "When the team is small enough that your departure would not have that same drastic impact, it felt like the right time, to keep my head high and say, look, everybody, it's been amazing but now I'm going to try something new."

And so, Mike Laidlaw left BioWare 14 years after walking into the old Edmonton office with no idea what he'd work on. He took at least a month off. Anxiety set in. "There were times, especially at the beginning, when I was like, oh my god, did I just make a terrible mistake? I walked away from a salaried position with a well-known developer."

It wasn't long before a studio contacted Laidlaw to ask him for his help. Suddenly, Laidlaw needed a lawyer and accountants, and was incorporating a consulting business called Croslea Insights. Laidlaw spent a week working with the studio on a deep dive of their project - something he had some experience doing with BioWare's projects and others across EA.

Since then, there have been waves of panic, Laidlaw says, and some fear now a paycheck is no longer a guarantee. But, he says, he feels exhilarated. "I get to have a ton of amazing conversations with recruiters where I mostly say I'm a little burned out right now and I don't think you actually want to hire me, but I'm flattered you'd ask." Laidlaw's even trying his hand at streaming on Twitch.

It's also been a period of reflection, and Laidlaw can now look back at his time at BioWare and assess, as best he can, the way the company changed as he grew with it. "The biggest single change I would say there is a lot more awareness of and adherence to an understanding of the benefits of process," he says. "Things were a lot more fly by night. We had barely any producers and absolutely no project managers when I started. We now have well trained, well empowered project managers. But it's never lost the urge to make you feel. It's never lost the urge to make you care about virtual people. I'll be brutally honest - I hope it never does."

When Laidlaw talks about BioWare he often says "we", not they or them, as if he still works there, as if he's still a part of the team, fussing over the future of Dragon Age. Our interview takes place half a year after the announcement of Laidlaw's departure, and still he slips into "we". Laidlaw worked at BioWare for 14 years. Clearly, it was hard to let go.

What is his legacy from his time at BioWare? Clearly, it is wrapped up in Dragon Age. While Laidlaw isn't the person who created your favourite character from the series, isn't the person who wrote your favourite line of dialogue, or designed your favourite quest, or wrote the history of the land of Thedas, he is the person who helped make it all come together, who helped it all just work, and who directed the creativity that made Dragon Age the wonderfully memorable fantasy role-playing franchise it is.

And then something I do not expect happens: Laidlaw chokes up. I can see tears form in his eyes. His voice starts to crack ever so slightly. I think he is about to cry, but he holds it together as he recounts the moments that meant the most to him during his time at BioWare.

"I've probably met over 100 people who've come up to me at PAX in particular and quietly taken me aside and said, 'I need to tell you how much your game meant because my sibling committed suicide and it got me through that,' 'I had chemotherapy, I'd take my laptop in and I got out of it. It was the only thing that could pull me out of the fact that I was being injected with poison.' 'I felt like I could never talk about the fact I was attracted to other men until I played your games. They've celebrated those people. They were there for me and they made me feel like I was okay.'

"You watch that and you're just like... people unload, in the best way possible, these stories. They wreck you, but it's cathartic. You're like, we did good. We did good, team!"

Laidlaw delivers a powerful anecdote about Dragon Age Origins' appearance at PAX Prime in 2009, one I present here in full - an appropriate sign-off for our interview.

"We had the big Origins booth where people went through and they were inducted into the Grey Wardens. You'd get a briefing. It was me in armour yelling at you. You'd get to play the game through the Korcari Wilds and you had to get back with the Vials of Blood, and if you succeeded in the half hour you had, which most people did, you got to go into The Joining. Our marketing manager, who was also in armour, would recite the litany of the Grey Wardens and then would smear fake corn syrup blood on your forehead.

"There was the guy who came to me and said - Jade Empire in particular was the game that got him through Afghanistan, two tours of duty in Afghanistan. So he brought me the patch from his unit and said, I want you to have this. I still have it. It's on my desk.

"There was the guy who lost his shit and was like, 'you're not putting blood on me!' And he sprinted out the door. He was like no! No blood! Screw you! That was really funny.

"And then, the one that really stuck with me is, there was a lady in a wheelchair. Not everybody in a wheelchair can't walk. Sometimes they can stand. She and her friends had gone by. I was the briefing guy, so I would stand outside looking all cosplay - I've never cosplayed except for that, and we wore real chainmail - like 28 pounds of metal for four days. I've never felt more manly. You had to shake it off because you couldn't lift it.

"This lady and her friends had cruised by the booth every day. There was a line around the booth, and people could see what was going on but they couldn't see it all. I was like, I'm going to go find her. She was in line. It was right at the end of the day and I was like, oh shit, she might be after cutoff.

"So I hammed it up: 'Special recruit! You're coming with me!' And her friends are like, er... and I'm like, 'yeah, support team, come on! Let's do this!' We brought her in. We put her through the recruitment. Her friends didn't play. They were like, no, this is just super cool, thank you. I'm like, no worries. So we go to play this and she gets through it and I'm like, yes! She got it! She goes through The Joining. After The Joining, anyone can come out and they can have swords they could hold up. We had this giant archedemon statue. We'd take photos of them holding the sword and stuff.

"She wheels up and there was this beautiful moment where she goes to stand up, and everyone's like, oh shit, and she does, because she can, of course - not everybody has that mobility issue. She gets up but she's holding the sword and there's this moment where she wavers - and I swear to god, I've never seen 400 people go, huhhh, all leaning in, and our community manager Chris Priestly was right there ready to catch her. Everybody got very tense for a second, and then she righted, and she was fine, she got the sword up and we took the picture. What Chris had been doing was like, all hail the Grey Warden! He would boom it because he had the most immensely carrying voice. But that time he fucking nailed it, just like, from the diaphragm. The audience, normally they're like, yeah yeah. But this time they just burst into applause. And she looked so happy. She sat back down and then away she went.

"I like to feel like somehow, at their very best, that's video games. That's the thing you get to do in this fantastical world that responds close enough to reality that you can lose yourself in it and for a moment you get to feel like a badass hero. That's what I want.

"I went back to the team - because of course not everybody gets to go to PAX, not everybody gets to do that kind of thing - I wrote an email and I told those three stories. One of our senior programmers at the time was like, wow, dude, I've never actually started to cry from an email before, but that was really cool. Thank you for that.

"I wanted to share what that felt like. That moment was just so crystalline. There are times when I look back at my career and go, you know, they weren't perfect, but we did okay. We made some Dragon Age and I think it might have been fucking worth it."