Call of Jihadi

Wafaa Bilal on the FPS the US government wants shot down.

In September 2006 Al-Qaeda became a game developer.

Its first release? First-person shooter "Night of Bush Capturing", a game free to anyone with an Internet connection and an open mind. Its six-mission campaign is constructed from genre features familiar to any gamer: work your way deep into enemy territory, shoot enemy soldiers before they shoot you and assassinate the leader.

Only, in this case the territory is America, the enemy soldiers are US troops and the leader in question is George W. Bush. Oh, and the developer is a notorious Islamic militant terrorist alliance.

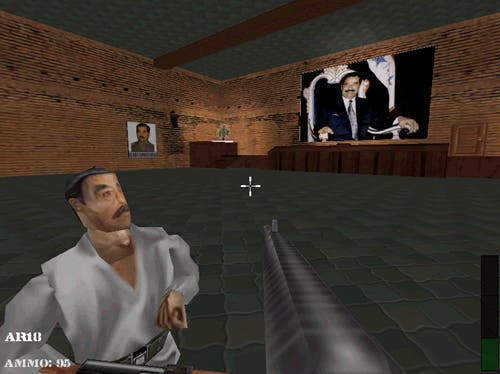

Programmed by a team from Al-Qaeda's Global Islamic Media Front, Night of Bush Capturing is in fact a modded version of an older, US-made game, Quest for Saddam, released by Petrilla Entertainment in 2003. Al-Qaeda's coders swapped out the artwork and textures of this earlier game - made with the Torque Game Engine - replacing the crude representations of Arab soldiers and anti-Islamic propaganda for equally crude versions of American soldiers and anti-American propaganda. This straightforward re-skin turned what was intended to be a rallying, pro-Iraq war game into a diametrically-opposed (but curiously symmetrical) attack on George Bush, his foreign policy and the nation behind his presidency.

At first neither game attracted much media attention, the former seen as little more than a basic, home-coded game that typified the popular American anti-Arab atmosphere of 2003, the latter a cheap and cheeky knock-off response from an international terrorist organisation. But recently both games found themselves at the forefront of a global debate on freedom of speech, artistic expression and the importance of story and setting in videogames.

Wafaa Bilaal is an Iraqi American artist and professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His latest artistic creation is a hacked version of Al-Qaeda's Night of Bush Capturing, in which he integrates himself into the game's narrative to present his own commentary on the conflict. He renamed the game 'Virtual Jihadi' before presenting it to the world as a piece to challenge viewers and inspire debate and conversation on some difficult issues.

In real life, Wafaa's 21-year-old brother, an ordinary Iraqi citizen, was killed by shrapnel during a firefight in Najaf. In his game the lead protagonist, upon learning of his sibling's death, is recruited by Al-Qaeda as a suicide-bomber, joining in the hunt for George Bush. Through his work Wafaa intends to "bring attention to the vulnerability of Iraqi civilians, highlight racist generalisations and stereotypes promoted in videogames, and demonstrate how British and American foreign policy is pushing Iraqi citizens into the arms of violent groups like Al-Qaeda".

It's a bold and broad purpose and one that saw Wafaa invited by the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to present a lecture and exhibit on this work at the end of February 2008. But the exhibition was only open for an hour before it was shut down by city officials. According to newspaper reports, the decision came after the College Republicans called the Arts department "a safe haven for terrorists". Eurogamer caught up with Wafaa this week to unpick the drama and examine some of the issues that have been raised by his game under these unusual circumstances. We started by asking him why he decided to use a videogame to get his message across.

"While I'm not a big gamer, I realise that games are now a huge part of our lives," he explained. "Videogames are moving from being reactive to more dynamic and interactive. For a long time we did not have interactive mediums but only reactive ones. I think that videogames can be more effective and powerful than other mediums such as film in conveying a message, in part because they are an active experience that allows the participant to create the narrative. Also, videogames are the medium of our time. As Quest for Saddam and Night of Bush Capturing were already out there, modifying these controversial examples added weight to my message."

And what exactly is that message? "I am trying to engage people in a conversation," says Bilal. "We, in the United States of America, have become isolated in a comfort zone. We are so far removed from the conflict. In a way I wanted to hold a mirror to people's faces to let them see the reality of this war's repercussions and explore the fallacy in our culture's denial of that disconnection and their stereotyping of other cultures. In a sense I want to reverse the role of the hunter and the hunted."

"The original game, Quest for Saddam, did not get any attention from the media and the state department because the ideas it promoted (that all Arabs/Muslims are terrorists) was the norm. Then when the game was modified to become the Night of Bush Capturing, the State Department labelled it as a terrorist propaganda and a recruiting tool. I thought that was strange because the only thing Al-Qaeda did is to replace the Iraqi skins with American soldiers' skins and Saddam's skin with Bush's skin. What exactly made it propaganda where it wasn't before?"