Code Britannia: Tim Follin

The pioneer of 8-bit music talks about the challenge of chip tunes, and why he's (sort of) coming back to gaming.

Code Britannia is an ongoing series of interviews with seminal British games designers, looking back over their careers and the changing face of gaming.

Previously, Code Britannia has focussed on the programmers who helped to define the British development scene of the 1980s, but they only tell part of the story. There were other innovators as well, such as Tim Follin, a man who managed to get the rudimentary 8-bit home computer systems to pump out honest-to-goodness music, rather than the vaguely melodic farts and beeps that most games mustered.

And, as with so many early games pioneers, Tim Follin got his start in the industry before he'd even finished school. He wasn't alone. His older brother, Mike, was also embarking on a coding career, but where Mike was interested in making games for the ZX Spectrum, Tim's fascination was with the sounds it could make. Already keen on music, he set about writing his own software driver that would allow the chugging system to produce convincing tunes. At the age of 15, he got his first break.

"I really fell into writing music for games through programming," Follin tells me. "I'd no previous interest in the idea and at that time it didn't really exist anyway. The first game I composed for was my brother Mike's game Subterranean Stryker. It used my first sound routine that made a one-channel phasing note sound, which at the time sounded quite impressive! Then while still at school other programmers I knew who were writing games, such as Stephen Tatlock, asked me to write some music for their games too."

His next theme for Star Firebirds reworked Stravinsky, and tricked the Spectrum into simulating two-channel sound, and that was followed by Vectron 3D. Only his third commercial composition, he was already creating epic three-channel soundtracks from a machine that was best known for squawks and bloops. All three were published by start-up developer Insight Software, and soon enough more established companies came calling.

1986 found Follin composing what, for my money, is one of the greatest tunes of the 8-bit era: the theme to Mastertronic's unassuming £1.99 spy romp, Agent X. The game itself was no great shakes, but the music was - and remains - a phenomenally catchy riff that builds into a genuine theme. It's a bona fide music track, a five channel rock epic, not just the same few bars repeated over and over that graced most rival games.

"I'm glad you liked it!" says Follin when I gush embarrassingly about my lifelong love for the Agent X theme and my childhood memories of holding a tape recorder up to the TV so I could listen to it in my bedroom. "I was listening to that again just the other day, someone sent me a link. It's hard to actually hear that one, I think I'd pushed the processor too far actually!"

Surprisingly, Follin's distinctive layered sound came not from a particular fondness for electronic music, but from his love of hairy old prog rock. "The motivation for making multi-channel sound was that I was really into chords and chord progressions at that point and was listening to a lot of early-mid Genesis," he explains. "I didn't see how I could write anything with one channel. It was actually quite a shock writing for the C64 after that, which sounded nice but only had three channels. That's why I immediately realised I had to 'ripple' one of the those channels to create chords, giving rise to that familiar 8-bit music sound. Listening back to those old Speccy tunes I've also noticed that I used the same phrases in several of them! Now that was laziness!"

Follin was one year into a music course at college when his first full-time job offer came along, from Manchester-based company Software Creations. He dropped out of the course and took up the offer. "I'd realised that the future of my musical education was going to be jazz, which I was interested in but that in truth depended on being very good at a particular instrument, which I wasn't," Follin confesses. "I can play piano and various guitars and other string instruments a bit, but I was never going to sit and practice for all those hours for some imaginary career in jazz. So it just happened that the job offer came at the end of the first year and it was a no-brainer - I had to take it. If I hadn't been offered the job writing game music I don't think I'd have pursued it as a career."

The change forced Follin to focus his talents - and not just on the Speccy. "The only music I'd written before getting the job was writing for the ZX Spectrum, which itself developed out of an interest in programming and trying to make the Speccy do things it wasn't designed to do. But certainly I was thrown in the deep end when I landed at Software Creations and had to work out how to approach it as quickly as possible.

"The best thing about working at that time was that I had the freedom to do generally whatever I wanted to do, within some broad parameters. I was fortunate in that just being able to make a sound chip 'sound' good, on a technical level, meant that musically I could do whatever I wanted to. Also the atmosphere around Software Creations at the time was about having fun. The boss, Richard Kay, spent as much time making people laugh as he did working."

The good times weren't to last, however, and the rapid pace of full-time development became an obstacle. "As time went on we took on more games and the turn around time got quicker, which did become a problem. My brother Geoff came to work with us around that time and he became known as 'the good one' by many of the programmers and designers because he could always turn around tunes a lot faster than I could, I think probably because he didn't have anything to prove and wasn't trying to impress anyone. I started to get crippled by the pressure of trying to be better and better. I liked to give the impression that I was too cool or too lazy, but in truth I started to have lots of 'blank' days, where I just couldn't think of any way to start, or would start but constantly change it, without ever finishing. I came to hate it towards the end of my time at Software Creations."

Follin's exit from Software Creations came courtesy of an unlikely source: independent US comics publisher, Malibu, which had set up its own video game development arm. Knowing the company was looking for UK talent, Follin organised an exodus. "That was actually my fault", he admits. "I called the boss of Malibu up - I used to do crazy things like that - and told him that we could get together a team in the North West if they'd set up offices here. And much to my surprise they did! We met up with them and soon sorted out the offices, then had to explain to the boss at Software Creations that we were leaving. That wasn't a great day. I think many there, including the boss, thought we were betraying them. In truth we just all needed a change - and a wage rise. Software Creations had become much like a work house and for me it was either leave the industry completely or move companies. I didn't really know very much about Malibu at the time except that they were offering 25 per cent higher wages! I certainly didn't know about their comic line or their history."

It wasn't just a change of employer, but also a change in technology, as new hardware from Sega and Nintendo moved the creative goalposts. "By the time I was writing for 16-bit consoles I was pretty much just providing recorded music," he explains. "In principle I was ready for it and looking forward to it, but in practice I struggled. With recorded music, suddenly the limitations are in performance. So although I could play a few instruments, I wasn't able to create what I wanted to - and I didn't have the budget to hire the musicians I needed. Eventually I got better equipment and found other ways of approaching it, but really by that point I was already on the verge of leaving the industry."

Malibu's interactive venture didn't last long however. Follin was only there for 18 months, during which time he contributed to just one game - Time Trax on the Megadrive - before spending "about a year doing virtually nothing and getting paid for it." When Malibu was bought out by Marvel in 1994, the interactive wing of the company was shut down, the staff were let go and as the new millenium crept closer Tim found himself relying on increasingly shaky freelance contracts.

"The biggest contracts I did manage to land were from producers like Dave Nulty (Ecco the Dolphin) and Dave Sullivan (Starsky & Hutch), who contacted me because they already knew my previous work and were happy to let me do what I wanted to do - I'm eternally grateful to the. But the industry has become very much like many other industries now, where the managers like to control everything and run everything past everyone else before they 'approve' it. It's over-management and is essentially the complete death of creativity. I actually did a few more games after Starsky & Hutch, such as Future Tactics for the Pickford Brothers, who were friends from Software Creations, Ford Racing and Lemmings on the PSP, but that was it."

And so much like his brothers - Mike went on to become an Anglican minister, Geoff moved into teaching - Tim Follin drifted away from games though not, as you might expect, into music, but into film. "I think if I hadn't become involved in games I'd have probably pursued my interest in films earlier on," he reveals. After directing the winning entry in a short film competition, he was offered a job at an advertising company, and then went on to set up his own production outfit, Baggy Cat. If you remember the Vistaprint TV ads from a few years back, those were Follin's work. "I've always been interested in film making and lighting, which I've always seen as part of music in a way. Much of my interest in music stems from hearing it within the context of a film, even if I'm imagining the film myself while listening to an album! So the two go very closely together for me."

So closely, in fact, that Follin's current project is one that brings together the many strands of his career so far: Contradiction, currently on Kickstarter, is a live action interactive murder mystery in which players must solve a conspiracy surrounding a controversial new motivational course called Atlas.

"I suppose it is a return to games," Follin muses, "but it's a return to a particular type of game that's driven by atmosphere and music. It's meant to be a small, cosy iPad game that you can get into to pass the time, I'm certainly not attempting to compete with big budget Xbox games like LA Noire. It came from an audio only then video-based adventure game idea Geoff and I had years ago, after we left Malibu. The technology at the time meant we never developed it further, but just last year I found the old documents we'd worked on and I realised the iPad would be the perfect medium for it, so I taught myself some Javascript and started developing it."

Of course, people are still understandably wary of the 'interactive movie' tag, given some of the poor examples we've suffered in the past. "I fully understand that wariness which is why I've taken a completely different approach to it," Follin admits. "The main difference is that Contradiction doesn't use a branching or multiple-option system. You don't arrive at option junctions where you choose from a list, all of which have to be filmed. In Contradiction you just get a certain set of tools that you can use whenever and wherever you want to - it's then up to you to make things happen. Nothing happens until you make it happen. The game is divided into chapters which correspond to hours. When you've completed all the puzzles for each chapter, time clicks on an hour and the environment fills with new events, locations and characters for you to discover, giving you new information and new objects. New characters arrive home, shops open and close, it gets late, people get drunk and start fights, you get attacked, new places become available - each chapter introduces lots of new events. The whole thing is meant to be more like watching a drama while being able to solve the problems."

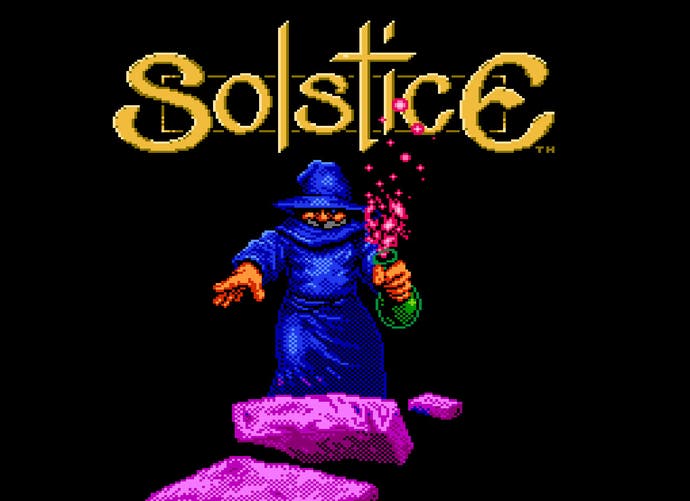

So now he's back, sort of. This will surely come as good news to his fans - such as top gaming tunesmiths Richard Jacques and Jesper Kyd, who have both cited Tim Follin as an influence - but the man himself is still endearingly bashful when it comes to the popularity of his early work. "I'm continually surprised by the interest," he says. "I can't honestly work it out! I do like some of those early tunes, but I'd say probably out of all of them there are only a couple I listen to now and still like, such as the Solstice theme or a couple of SNES tunes. It's bizarre really that people like it, I've no idea what they're getting from it to be honest!"