Left 4 Dead

The best thing since sliced dead.

Valve is approaching a "pretty big milestone". Chet Faliszek calls it "lockdown". It sounds like a big deal. Remembering back to the summer of 2003, when "September 30th" was starting to rust, I feel suddenly uncomfortable about effectively downsizing Valve by eight people for three crucial hours of team-based online zombie duckshoot. Oh well, it's their funeral. "We're pretty fickle gamers here, especially since we don't have much time to play games, and it's not hard to get people to play Left 4 Dead," says Erik Johnson.

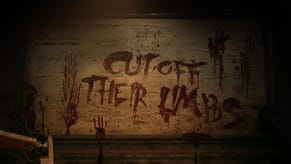

Nor is it hard to play, as we explained when we last did that. The scenario's simple: virtually everyone in the world except your four-man term of survivors is infected with a zombie virus, and you need to escape to safety together. It's the "together" bit that presents challenges. What's the key to making people respect it? "We've found that positively reinforcing good co-op play was more valuable than negative reinforcement of bad co-op play," says Johnson. "Making sure you don't have one person trying to ruin the experience, that's the easy problem. But making sure new players know when they've done something well is a lot more difficult from a design standpoint."

Key to achieving that is the line-up of Infected "bosses". They're not bosses in the traditional end-of-the-level sense, but turn up at unpredictable intervals and present more of a challenge than the rank and file zombies, who just charge at you screaming in great numbers ("We put more enemies on-screen in this game than we have in any of our other games," says Faliszek). The bosses, Valve says, have been designed with attacks that demand a concerted response. "When someone's being choked by a Smoker they're going to die unless you deal with it," says Johnson. "Being the person who kills the Smoker that's going to end a person's game is very rewarding." So each boss drives the survivors together.

It helps that you don't entirely die when you run out of health - you just fall to the ground, still able to fire off your pistols, and lie there while 300 healthpoints tick down to nought. If someone gets there they can revive you, providing they're not interrupted. But if a Hunter, who can scale walls and pounce from great distance, straddles you, he needs to be blasted off urgently. Elsewhere the Tank (think zombie Ben Grimm) can pick up bits of the ground and throw them at you, and toss cars around, so he needs a lot of guns trained on him. And the Boomer is probably the most ingenious - a pus-filled waddling bomb of obesity, he explodes if you shoot him, scattering the group, but if he vomits on you it obscures your vision and the low-rank Infected target you, drawing the group in to protect you again, and increasing the risk of the inevitable Boom finding more victims.

Merits and demerits are handed out at each checkpoint and accumulated when you complete a scenario. Meritorious acts include healing a friend (fail to do so as a team and they spawn in a locked room later in the level and have to be let out), staying on your feet for a whole section, shielding someone from a back attack, gathering headshots - that sort of thing. But the demerits are the more interesting. "Forgetful" is if you take a chunk out of an enemy and they come back to haunt you or your team. The game also penalises for friendly fire, but Faliszek indicates that it understands the truth of things. "You might notice in the bottom-left of the screen it says 'Pressplayer attacked his own team-mate', but if there's people between you, or you clearly did it by accident, it doesn't penalise you." You won't be pulled up if someone runs across your firing line either; in fact, they'll be cited for recklessness.

It shouldn't be surprising that Left 4 Dead exhibits intelligence. Primarily developed by Mike Booth's Turtle Rock, with whom Valve's collaborating, the game hinges on the idea of an "AI director". It's not so much about telling the Infected classes that force players together where to go (in many cases the Infected are controlled by opposing players, anyway), but about dictating the game's rhythm and pace; determining how many Infected are going to swarm over that rooftop, or erupt from that doorway, or whether you're due for a break. "One of the first demos Mike showed us had these bars that measured player stress, and that's the thing he's trying to control," says Johnson. "If you do the same thing over and over again, no matter how well you execute on that, players aren't switching gears enough and it gets boring, or too stressful, and the game feels cheap. 'Combat fatigue' is a term we use a lot when we playtest our single-player games. So Mike can watch stress levels and make sure players aren't having high-amplitude events again and again."

Unpredictability is a welcome natural byproduct. Normally in press game demonstrations there are cheesy stage-managed reveals. But Faliszek and Doug Lombardi, Valve's marketing director, who's playing next to me, are constantly surprised by what's going on. In one case I've been playing as a Hunter on the Infected side for several minutes, and I've clambered onto a rooftop that overlooks a petrol station the survivors have to pass through. They have no idea where I am. One of them, the female character, is bringing up the rear, and I'm stalking her. I measure my pounce, and then propel myself off the rooftop with the goal of pinning her and causing chaos. Except I never make it, because almost at the point of impact both her and I are blown sideways by the explosive force of the petrol tanks in the forecourt next to us, which have been set off by shrapnel in another firefight with the horde. It's comic, disorientating, and completely unexpected.