Darfur is Dying

When videogames discovered ethics.

Endorphins for small victories: Is that all videogames are really about?

Tidy the blocks in Tetris to make them go away to make room to tidy the blocks in Tetris.

Is that it? Is making a great videogame just about finding a good cog and wheel and convincing a player to turn the handle for 30 hours? Is satisfying gameplay just a case of piling high little demands, each accomplishment whipping the player a bit higher into a chemical state of ecstasy until that post-coital flick of the power-off button? Is there really no point to videogames outside futile distraction?

Or could a videogame perhaps inspire an ideological shift in a player? Or some political change? Could games encourage charitable acts? Or perhaps put players in uncomfortable shoes and situations to promote some form of solidarity with the suffering and the oppressed?

Could videogames ever actually change the way people view and interact with their world like a Hotel Rwanda, a 1984, a Nevermind the Bollocks, a Supersize Me or a Mein Kampf?

Game producer Susana Ruiz was chewing all these questions when she visited the second annual 'Games for Change' conference in New York during October last year. There she met Stephen Friedman from mtvU. He was there to announce a substantial grant to be awarded for making an interactive game themed around the current crisis in Darfur. For Susana the idea was too important to pass up - and with MTV and Reebok sponsoring an entire development team to make the game, the financial and logistical support was already set in place.

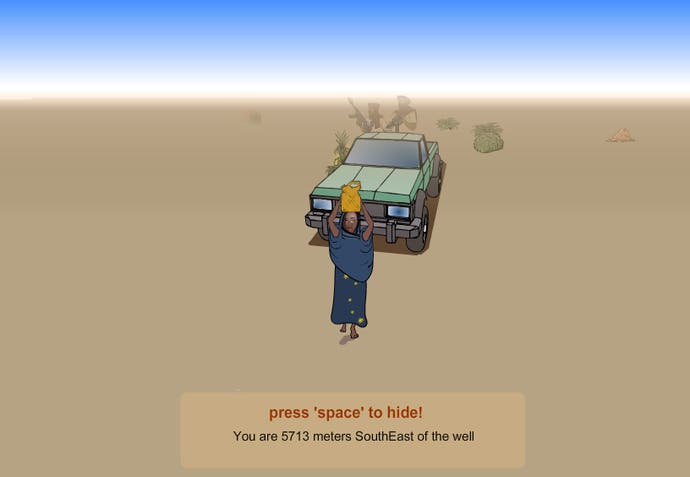

Susana won the pitch and created what is perhaps the first true survival-horror game in which players experience life as a Sudanese living in Darfur in 2006, fighting to stay alive not from the threat of Space Invader aliens but from real world bullets and sun-cracked soil. Since its release this year (http://www.darfurisdying.com/) nearly a million people have played the game.

Eurogamer caught up with Susana to ask some tough questions of videogames.

As part of my graduate studies at the Division of Interactive Media in the University of Southern California's School of Cinema-Television, I was already focused on the notion of bridging the form of digital gaming with content of sobriety, weight and urgency. I originally wanted to create a game based on the Gacaca post-genocide trials in Rwanda. But then I heard about the Darfur Digital Activist competition and it seemed an opportunity too good to pass up.

To produce a game concept (game design document) and a representative prototype, the student team took approximately two months. However, half that time was spent reaching out to experts for education and advisement as well as having many brainstorming meetings as a group. It was imperative that the group become as informed and sensitized as possible, even before producing anything, so that the ideas brought to the table would represent the reality accurately and hopefully be insightful.

The goal of the game is to raise awareness about the Darfur crisis and to motivate involvement on the issue by affording players basic and uncomplicated ways to become involved. It is indeed difficult to measure the success of a game whose goal is not to turn a profit but rather seeks to incite societal change. According to mtvU's traffic numbers, more than 800,000 people have played the game over 1.7 million times since its launch on April 30th. Of those, tens of thousands have participated in the activist tools woven into the gameplay - such as sending emails to friends in their social networks inviting them to play the game and become informed about Darfur, as well as writing letters to President Bush and petitioning their Representatives in Congress to support legislation that aids the people of Darfur.

The notion of "fun" can be problematic in this context. Too often, I have witnessed the rhetoric of such an argument impede compatibility and progress. I think that media experiences can be engaging while not necessarily fun or even comfortable, as can be the case often with film documentaries, music, graphic novels, and so on.

It has previously been the case that, early on in the evolution of a new mass medium, entertainment was a leading motivator (i.e. cinema, television, etc.). As videogames evolve and mature (along with videogame-makers and players), I do think that there will be more meaningful social commentary inserted into the play - either at the forefront of the experience or in the background. The game industry (from the giant developers/publishers to the small independents) also has to explore funding and business models for such projects that do not necessarily seek high profits yet require substantial production budgets. In this last regard, the field shares similarities with film documentaries - many of which do not reap high economic profits, but do garner critical acclaim and have social import.

The unique element of agency that games inherently provide is indeed why it is an incredible challenge to design experiences that deal with real-world injustices and tragedies. The designers must become highly educated, and diverse mindsets and domain expertises must be brought into the production. It seems to me that this is starting to happen within the academic sphere, but is yet seldom the case within the mainstream. This is a unique demand but an essential one if profound and appropriate game representations about important, sobering and uncomfortable issues are going to exist. Agency may present a new and risky challenge but I think that we cannot turn away from exploring whether it can also provide real impact.

I am not certain that a game would be "a more effective tool" than a TV episode. It is true, however, that each medium and genre appeal to different audiences. "Darfur is Dying" is meant to serve as an entryway into the crisis for an audience that would not necessarily find a New York Times or Washington Post newspaper article on the issue accessible. For this reason, one critical design point was that context should trickle in bit by bit and not overwhelm the player at the outset. Often, this high entry barrier presents a hindrance for videogames.

Furthermore, while it is a challenge to understand and measure the success of a game like "Darfur is Dying", it does contain - embedded in the gameplay itself - ways to take real-world action. This type of player activity can indeed be measured and can be thought to be a direct link between the audience and the cause/issue. I think that this type of interactivity is yet latent with potential to affect real-world awareness and action.

We did not set out to entertain but rather to inform, engage and motivate. Early on in the process, we were inspired and driven by what Pulitzer Prize winner Nicholas Kristof wrote for his New York Times column in a piece detailing pro-Darfur activity in American campuses. He writes of the "way generations of Americans acquiesced in one genocide after another - only to apologize afterward and pledge 'Never Again'. So out of the miasma of horror that is Darfur, something uplifting is taking place. Ordinary Americans are finding creative ways to respond to the slaughter, so that they personally inject meaning into those traditionally hollow words: Never Again."

"Darfur is Dying" aims to offer a faint glimpse of what life is like for the millions of Darfurians that have been displaced by this genocide. Humanitarian aid workers who advised us on the development of the game have said it is hauntingly real, and we hope that feeling leads those who play it to become involved in helping to stop the crisis.

Furthermore, creating gameplay that is engaging, that informs, and that motivates real-world social change is a grand and elusive goal. As a result of creating "Darfur is Dying", we learned first-hand that the process of discerning appropriate representational aesthetics as well as appropriate interactive mechanics and play metaphors is a challenging and sobering endeavour. The student team thinks of "Darfur is Dying" as a work in progress and hopes to continue improving and advancing it.

This genocide can be stopped. Our world has the collective resources to end this suffering, but it takes personal and political will that is lacking. We hope "Darfur is Dying" will continue to motivate more individuals to take action to help end the killing and suffering in Sudan.

This is a very interesting question. We don't know. It is true that aid organisations such as The International Crisis Group (which worked in partnership with mtvU and The Reebok Human Rights Foundation on this Darfur Digital Activist Contest) are always trying to strategically stretch their resources to achieve the most impact. And while we are certainly not experts on these methods, we do know this crisis has been occurring since 2003 and if music television companies or sports apparel companies want to put forth creative efforts to try to correct some of the injustices in the world, we would not have an ethical qualm. Furthermore, assuming the process is legitimate and genuine, this can actually present a viable funding model for social issue-driven game projects.

During our production process, it was critical that we continuously sought out the opinions and advice of scholars and experts on genocide and Darfur - including those that have spent time on the ground in the region. Of course, the idea of a videogame tackling what they have devoted their lives to was initially confounding to some. However, the situation is so desperate that for many of these experts, the notion of trying something unorthodox was in the end, something they not only found intriguing, but something they actively supported.

I think that in time - with more experimentation resulting in more social issue-driven games out there - along with appropriate metrics to measure their effectiveness, it will be accepted as the norm.