Peter Molyneux of Lionhead Studios - Part One

Interview - Peter Molyneux talks about the creation of Black & White, from creatures and plastic eggs to philosophy and religion

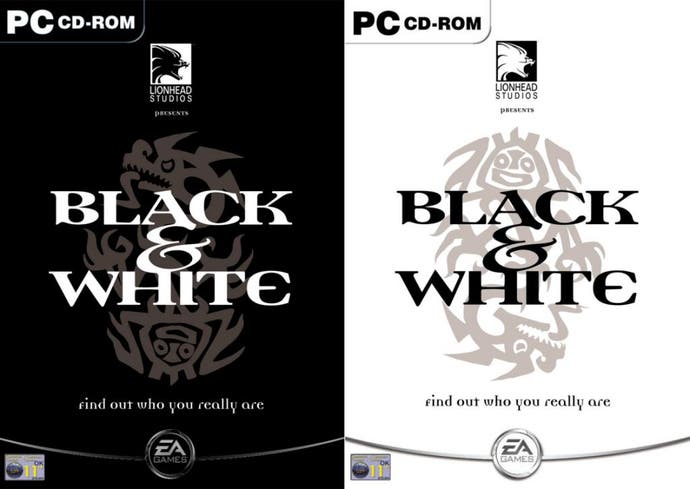

Peter Molyneux is truly a man who needs no introduction, the brains behind classic hits such as Populous and Theme Park. With his latest magnus opus (Black & White, one of this year's most eagerly anticipated games) recently sent off to Electronic Arts for final testing, Peter dropped in on a press event unveiling the forthcoming PlayStation port of the game to have a chat with the European press.

Everybody Wants To Rule The World

Peter is perhaps best known to veteran gamers as the man who put the god game genre on the map with the multi-million selling strategy game Populous. Black & White marks Peter's return to the genre that he helped to create, but why does he keep coming back to it? "A lot of people have speculated that I probably want to take over the world or something", he told us.

But although his softly spoken English accent and dark sense of humour would make him a perfect Bond villain, the truth is sadly rather more prosaic. "A lot of what I'm trying to do is remembering when I was a kid. When you're a kid, you can just be given a couple of sticks and a pile of sand, and a child can create the most amazing scenarios. And in a way that's what I'm trying to recreate. One of the reasons I like god games is that as a designer I give you the world, and it's up to you what you do with it. If you choose to treat that world in the most ridiculous horrible way, you can do, and I don't hold anything back."

The original idea for Black & White came from Peter's work on Dungeon Keeper, a game that he admitted he "wasn't enormously happy with". In Dungeon Keeper Peter turned the traditional fantasy storyline on its head by putting you in the role of an evil overlord trying to build up and defend a dungeon (complete with torture chambers and vampires) from the do-gooding heroes and rival warlords. Black & White takes this idea to the next level by allowing the player far more freedom in how they approach the game. "The idea came to me to make a game where people can be whatever they like - they can be good or they can be nasty, they can do nice things or they can do evil things. And then, as a designer I don't have to think about it - it's up to the player how they interact with the world."

Cruel To Be Kind

The result is a game which says as much about the player as it does about Peter Molyneux and his team at Lionhead. "What you will realise by the time you get to the end is that there is nobody judging your actions, there is no other force, a higher god. You are completely free to do whatever you like, because you were called into the world by the prayers of the people."

"Actually what is judging whether you are good or evil is the little people. And this is the philosophical point behind the game. It's sort of inspired by the saying 'if a tree falls in a forest how do you know it makes a noise'. So if you do evil things and nobody sees you do them, you don't get any more evil for it. But if you do evil things in the middle of a village and lots of people see them then you get a lot more evil. So you realise that the little people are judging you, but they've got no real power over you."

Which is obviously lucky for Peter, who admitted that "my little villagers have just taken unspeakable cruelty". It's no doubt which side of the divide Peter comes down on then. This is a man who "will literally destroy and kill every single unit in the map, and do that for hours on end" when playing Red Alert or Age of Empires. "I am black", he confessed, before trying to excuse his terrible crimes by claiming "I have to test these things, and obviously being able to be cruel is a great stress relief. And I've been under a huge amount of stress to finish this game, so there have been .. well, the stats accumulate the total number of people that you have killed or sacrificed, and it does run into the thousands. But that's because I had to test all the miracles and stuff!"

Out Of Africa

In a way then Black & White is a very moral game, as the way you treat your followers has a very visible effect on the world, changing everything from the landscape and skies to the behaviour and appearance of the giant creature which accompanies you throughout the game. "I think as it turns out it's done that, but it wasn't one of the great ambitions of the game to make a moral statement. Certainly there have been lots of times when we've sat down during development and thought it's quite cool that people judge you and they either respect you or they fear you. But what I'm really talking to you about is mechanics, and side effects of what we have implemented."

One interesting aspect of this which sadly didn't make the final cut was the idea of selling two versions of the game at different prices. "Originally we wanted to do a black box which was two pounds cheaper than the white box, and the white box you paid more but that went directly to charity. It's a really nice story - we'd actually arranged to set up all these webcams in African villages, so that people could watch the money from Black & White building buildings. And there was another plan after that, where either you got a voucher to send off money to charity or a Mexican lottery ticket in the black box. But again, you can understand retail - doing anything special like that is just not fun for them. It is a bit of a hassle to stock two different price points [for the same game]."

If the moral aspect of the game is largely accidental though, the battle between good and evil is very much at the heart of it. "Every single one of my favourite films have always led up to one huge battle, and the battle is always against, and this is the interesting thing in Black & White, someone who is in film terms the opposite of what you are", Peter explained. "And that's true in Black & White, so if you are good then the people that you fight against are evil, and vice versa."

Unreasonable

The divide between good and evil is not always so clear cut though. "If you play the game you realise that perhaps sometimes the little people in the world unreasonably ask you for things. At the very start you're doing fairly minor things, opening gates and saving the lost brother and all that. In the back of your mind you're thinking, 'well this is pretty trivial stuff as a god', and you really want to be free."

"There's a very interesting thing, right in the first land, and it's a stupid thing, but in one of the challenges somebody outside the town asks for some food, and you would think 'oh, well if I give him food that's gotta be good'. But the only food that's around is in your main village, and you've got to take food from them. So as far as those people are concerned you're taking their food, which is evil."

"There's lots of little things like that. You would think, for example, that any kind of killing would be an evil thing to do, but that's not true. In one of the later lands there are packs of wolves that hide in the forest. If you kill those wolves, which are going out and killing people, that's good. But if you heal the wolves that's evil. So it's not always as clear cut as you might think. I can't say to you 'if you want to be good in this game, don't kill anything'; that's not true."

So 'Thou shalt not kill' style commandments are out then. In fact, Peter has been careful to avoid any obvious links to real world religions, which is probably as well given how touchy most of them are. The overly talkative taxi driver who took me back to the station after the event certainly thought that the idea of a game in which you played a god was sure to offend somebody when I tried (and largely failed) to explain Black & White to him. "I'm inspired by religion, I think it's been a major influence", Peter told us. "In the game there are some religious references, but you will see no icon there of any particular religion. What I didn't want to do is to upset anybody."

Plastic Egg

Along with the central idea of choosing between good and evil, one of the other major elements of the game is the "creatures", giant semi-intelligent animals which can be trained like pets and carry out tasks for you.

"The idea for the creatures came right at the end of Dungeon Keeper", Peter explained. "At the end of any project you're working flat out about 20 hours a day, and you don't see any human beings other than the people that you work with. I had one of those stupid Tamagotchi eggs, and I'd really grown attached to it - I was taking it around with me everywhere and feeding it when it beeped. But I was a bit frustrated that I couldn't be nasty to it."

"In the end I left it on the table, and one of the testers who was testing the game, in fact the head tester Andy Robson who is testing Black & White now, drowned my Tamagotchi in a cup of coffee. It was honestly as if a piece of my family had been taken away from me. And I thought at that time, if I could create an emotional attachment to a little plastic egg thing, if we were able to create something which changed, something that you could interact with, something that learned from you, just how powerful that would be. So that's where it came about from, the fact that my family turned out to be this little plastic egg."

The coffee cup incident also led to the decision not to allow creatures to die in Black & White. "Rather like my Tamagotchi egg being drowned in a cup of coffee .. after that, the thought of ever touching another Tamagotchi egg just made me sick. I couldn't bear the thought of going back, and I realised that if your creature died and you had spent all these hours growing him up, making him unique, having to do that all over again .. nobody would go back to the game again. So your creature gets hurt, he's out of action for a long time, many many minutes - there's a big downside - but he doesn't die."

Creature Comforts

Which is probably as well, because the creatures in Black & White are like pets, and losing one after playing the game for days on end would no doubt be something of a traumatic experience. "The amazing thing about Black & White is, when you do get your creature, and it's just not possible to convey this in a demo, is the emotional attachment you have with your creature. And you do feel proud of him, and you do feel like he is learning from you."

The avatars weren't always going to be animals though. "The original creature was a little boy and a little girl that started out as normal people and grew up into these huge giants. But we found that the mechanism of rewarding and punishing a creature works quite well on the creature - you don't feel too bad about, you know, stroking a cow in the genital regions. But when it comes to a little girl or a little boy, doing that would obviously bring up a few concerns. And then being able to slap them as well would bring up an awful lot of concerns. It just seemed very aggressive to do. I mean, imagine taking a human being around on a leash - it just wouldn't work."

Apart from the obvious desire to avoid the moral outrage of the tabloid media for encouraging child abuse, there was another reason for using animals instead of people. "If you saw a human being walking around and I said 'Oh, it can learn anything you can do', it just seemed weird that you couldn't talk to these people, you couldn't converse with them. And so we took the decision not to include any human creatures but just animals."

In hindsight it was a great decision to make, as the animals give the game a lot of its character. "Because .. you know .. animals, a two hundred foot cow standing on two legs is a little bit surreal. Let's be completely honest about that, it is a little bit surreal. But the funny thing is, they seem more human than humans."

-

Peter Molyneux interview - Part Two

Black & White preview (PSX)

Black & White screenshots (PC)

Black & White screenshots (PSX)