In media Rez: the return of Tetsuya Mizuguchi

From Sega Rally to Child of Eden, the past, present and future of the influential designer.

In the sweat mist of a late 90s techno hall, Tetsuya Mizuguchi got his first glimpse of what would become his life's work. The young Japanese designer, still fresh from the success of creating one of Sega's biggest arcade hits, found himself on a balcony at Zurich's Street Parade - an offshoot of Berlin's celebrated Love Parade - watching out over a crowd lost to the rhythm. "This DJ is playing, and 100,000 people are moving with the music. The sound changed, and the movement changed. I watched from the top, and was like 'wow, what is this?'" What if you could play this, Mizuguchi thought to himself. What if he could turn this into a game?

It's an idea that still occupies Mizuguchi when I meet him in Tokyo, where we walk away from the sweltering mob of Roppongi towards its quieter back-streets and to the boardroom of the mobile game studio where he's currently consulting. Mizuguchi talks in fractured, thoughtful English, taking his time as he gathers his words; I've always found talking to him like one of those slow, stilted yet utterly engrossing conversations that takes place in the early hours while your ears are still ringing from the nightclub you've left behind.

Music is vital to Mizuguchi, of course, from the electronica spine of games such as Rez and Child of Eden through to the rhythmic puzzles of Lumines. As a teen in Otaru, on Japan's northern isle of Hokkaido, Mizuguchi became besotted with music television in its infancy, tuning in to MTV to get lost in the sugar punk of Cyndi Lauper, XTC, and Duran Duran. The language of the 80s music video, with their detached sense of cool and angular neon, would leave an imprint; at university, while studying media aesthetics, Mizuguchi took a Sony beta pro editor to his room where he'd tinker with his own video remix of Art of Noise's Paranoima.

Music videos were Mizuguchi's first passion, and his first ambition for a vocation. Moving to Tokyo, he took up work at an advertising agency for a TV company, but it proved to be a dead-end. "I tried to learn what was creative in TV and advertising," he says. "But I could feel it wasn't my future. It was a very limited creativity. I lost my way."

He soon found it again in a Tokyo arcade. Sega ruled the arcades of the early 90s, its extravagant cabinets working in unison with its blue-sky action to create perfect throwaway thrills. None was more extravagant than the R-360 cabinet, a swirling cage of plastic and servos that could spin the player upside down. "I saw that, and I was like 'wow'. I saw the logo, Sega, and thought that's it - I want to join Sega!" Mizuguchi went straight to the company's headquarters in Haneda. "There was no appointment," says Mizuguchi with his crooked smile. "But I wanted to join this company. The lady at reception, she said to me, you need to have an appointment. So I said, okay, give me an appointment!

"Sega wasn't such a big company at the time, it was very small. I got an appointment with the human resource division, then I got an interview. I forgot what exactly I said, but they picked me out. I said to the director of R&D, I explained to him I don't want to make a game. I want to make a future game. The current game, it's too young, too childish. Games should be a new entertainment form, in the future. This is too small. This is still otaku culture. But it's going to get huge in the future. I believe that. And I want to do that.

"Then he says 'Oh, you don't want to make a game? This is a game company. But I like you!' So I joined Sega. There were no other candidates for me like Nintendo and Namco. It was straight to Sega."

Video games were on the cusp of an evolution at the time, and Sega was at the forefront of pushing much of the the change through. Mizuguchi came over to the UK in 1991 to meet with Virtuality, the company at the centre of the first wave of commercially available virtual reality headsets, as Sega explored ideas for its own headset first. His first project, a non-playable interactive ride called Megapolice, was similarly enamoured with new technologies, leaning on partnerships in the burgeoning 3D and CGI industries. It's that same desire that led Sega to meetings with Lockheed Martin that would lead to the creation of the Model 1 board, the power behind pioneering 3D games such as Virtua Fighter.

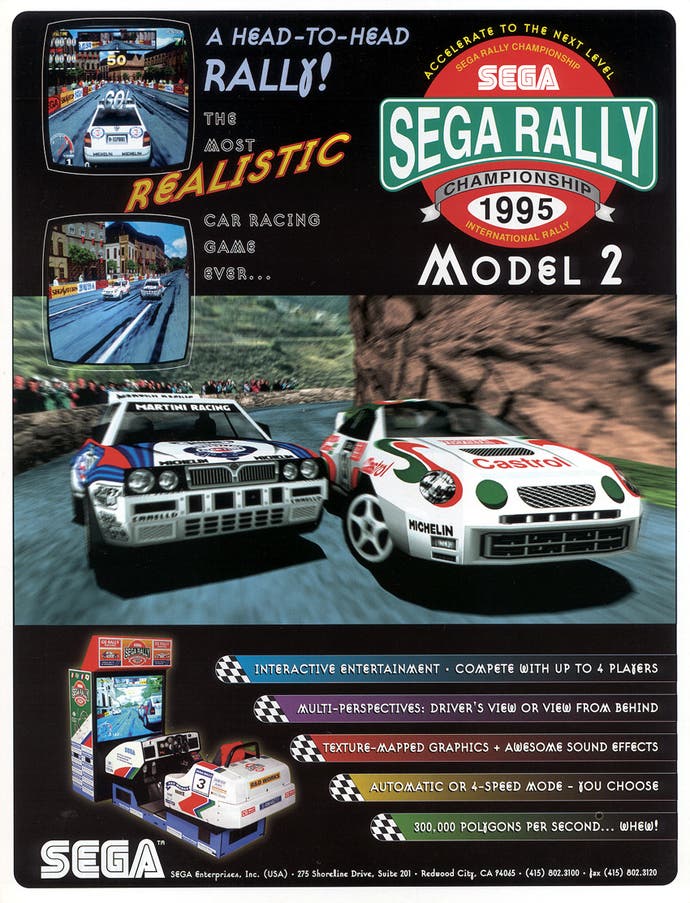

Mizuguchi, still taken with the idea of making a 'future' entertainment, marvelled at the possibilities. When the Model 2 board was introduced, allowing the use of textured polygons, he decided it was time to assemble a team. His principal hire, Kenji Sasaki of the original Ridge Racer team, would help Sega bring the fight to Namco in the battle for supremacy in the then dominant driving genre.

The game that followed, the mercurial Sega Rally Championship, was made by a team of 12 in just ten months. "To me it felt like a very long, long time," says Mizuguchi. "We were so young! I was 28. And everybody was in their 20s - 25, 24. It was everybody's first experience to make that kind of 3D, CG game. Most of the people, it was their first time making a driving game, including me. And we wanted to make some revolutionary game!"

The genre was congested, not least with Sega's own entries such as Daytona USA and Virtua Racing. Mizuguchi and his team decided not to rely on the knowledge elsewhere within the company. "We were like, okay, let's forget about them and do an original thing. What can we do with the textures we can use? Let's forget about circuit games. Let's go out to nature. I was into rally itself, and the World Rally Championship in Europe - real cars with many stickers that drive through the town and the forest and the desert, with many people screaming. I felt this passion, and wanted to put that passion into the game."

Development was short but eventful. A key part of Sega Rally Championship's appeal is its drift mechanic, a delightfully elastic, analogue handling model that was in contrast to the more digital models employed by its contemporaries. It's a model inspired by the team's own experiences during the creation of the game. "Many times I took them to the circuit in Japan. This was a dirt circuit, no asphalt. We borrowed real rally cars - and we got insurance, so if we hit the car that's okay."

Cars were hit. Numerous times. Mizuguchi himself had an altercation with a wall that left a car half-crushed, one of several vehicles sacrificed in the name of authenticity. "That kind of experience, it was really important. If you slide the car and hit the brake, what kind of movement do you have? When you feel the axle slide, it's so much fun! Making the game, we had big arguments. What is the drift technique? What's the correct counter steer?"

Sega Rally Championship would also be one of the pioneers of licensing real-life cars for video games, a bedrock of the genre today. "I had to negotiate with Toyota and Lancia," says Mizuguchi. I went to Toyota to negotiate with them, and I met the head of promotion. I explained my plan - and they said no, no, no, no game please. The game audience, it's very young and they're not our customers. They felt it was a bad influence for society.

"But we wanted to change history. We wanted to change everything! I showed our demonstration, and we'd put the Toyota Celica in there with all the stickers, and drifting and jumping. Then he felt something. This is not like the others - this is a new game! After a few hours, we had a very hard discussion, and I told them if we could have some licence from you, this arcade machine is going to spread to the world. It'll be a big promotion - and everyone will want a Celica.

"It was not so easy to get the licence. He said if Fiat - who did the Lancia Delta - if they accept, then we accept. So I go to Sega, and tell them I want to go to Italy - immediately! The head of Sega's R&D said no. We had no insurance. If you go there and they say no, that's it. I had to go. This is my life! Then he said, okay, let's go. I went there and met the guy, and I explained the same thing. They were so impressed. Then I them to sign, go back to Toyota and got them to sign. That was the first game that had that kind of collaboration with real companies. I was really proud."

Sega Rally Championship came out in arcades in 1994 and was met with success, locking the team into a series of similar titles. Development of Manx TT SuperBike, a game based around the long-running road race around the Isle of Man, was hampered by the team's thirst for authenticity when several members had bike accidents during the course of their research, including one incident which took the main designer out of action for a short while.

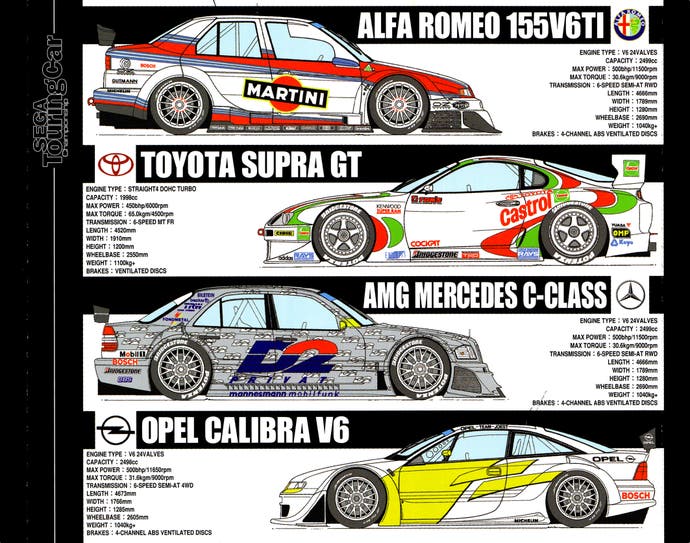

Sega Touring Car Championship, which was to release in 1996, was set back by its alarmingly short development time. "That was terrible for me!," says Mizuguchi. "We tried to make something professional. With Sega Rally there was a beautiful alliance. This was a circuit racing game, though, and we had no time to create it. It was only four months. For many reasons, after Sega Rally Championship, our mission was to make this new game in four months. That was very tough and crazy. I was so exhausted."

By the time of the inevitable sequel to Sega Rally in 1998, Mizuguchi had grown tired of the racing genre. "I was so excited to make the first Sega Rally. But Sega Rally 2 - I felt it was more like engineering. What is there that's creative, that's the future of the racing game. After I finished Sega Rally 2, I felt I should say goodbye to racing games. I'd produced four or five, but I had no self-confidence in making more. There was a big big future for the racing game, but hand on heart, did I want to do that? No, it's not my job. You know Yamauchi-san [creator of Sony's Gran Turismo series], he's doing a great job. He's the right person! I'm not like Yamauhci-san. He's so car obsessed. I'm not!"

The development team was handed over to Sasaki, with Mizuguchi starting another, smaller team. United Game Artists, the new studio within Sega set up by Mizuguchi, was established to explore more casual games on Sega's new home console, the Dreamcast, and its first project saw the designer's earlier obsessions come to the fore. "My inspiration was music lovers, and the music fans that exist and the game fans that exist. They're huge, huge areas, both - but there was no sync between the two. Up to that point, we had a technology problem. It was impossible to use sound in game design. Timing games, or the sound effects getting the music, that was impossible at the time."

Space Channel 5, the first game to emerge from United Games Artists, was like the music television of Mizuguchi's childhood writ across a playable package, Ulala strutting through the galactic corridors like Max Headroom's campy sister. Alongside the likes of PaRappa the Rapper and Vib Ribbon, it was part of a wave of rhythm-based games - a genre that Mizuguchi wanted to take even further.

"I wanted to make a shooter. But not a shooting shooter game. You shoot, you get sound effects, sound effects become the music, and you feel a trance. You feel good. Many people love shooting games. Many people love music. They love going to clubs, screaming, getting high. The power of music is very strong. Maybe this is too abstract, but we want to change something. So we needed a big shock. Anyway, let's start to make this. It's an experiment. I had then a small team, three to four people, some designers and programmers.

"First, I had this very fuzzy image, but it was getting concrete. I took half a year to create a very basic concept. In my mind, something was moving and if I shoot it I get a sound effect. The sound effects become a rhythm, then it becomes music, like it's a musical instrument. And if you could play, you could make a new track, like a DJ playing. It's like a combination."

Mizuguchi's own love of nightlife fed into his ideas - and the trip to Zurich's Street Parade in 1997 saw it all come together in sharp focus. "In my mind, I recalled Kandinsky. And I thought, wow - this is a digital Kandinsky. If he was around now, what kind of a new game, what kind of an experience, would he make? That was the inspiration. It was a long trip, but many, many inspirations came to me."

Synaesthesia - the union of the senses, and a neurological phenomenon that is often associated with the work of Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky - lies at the heart of much of Mizuguchi's subsequent work, from the abstract shooting of Every Extend Extra to the musical sweeps of Lumines. Its expression was at its most pure, however, in Rez - a game which was once title Project K in respectful deference to its inspirations.

Rez released at a strange time for its developer, coming out on the ill-fated Dreamcast during its final days as well as on the PlayStation 2 - the first game on Sony's platform from a Sega that was transitioning from platform maker to software publisher. "I showed the first Rez at a PlayStation party, and I played in front of people. I never explained it to people - just played. Before that day, I changed the colour of my hair to silver. I wanted to express that kind of feeling. After I played Rez, I left the stage. That was performance!" The reception after Mizuguchi's performance was rapturous, with Sony Computer Entertainment's founder Shigeo Maruyama taking to the stage afterwards to praise this strange new game. Mizuguchi's hopes for Rez were high.

"I thought we might have a big hit, but sales weren't so good. So then, I was a little bit depressed. Some people were getting manic about Rez, but some people are saying this is not a game. It was so split. I was a little bit depressed. Some people told me, Rez, it's too new! But you have to think about the long-term, 10 years, 20 years. You opened the door. And then, the many games in the future will take some influence from Rez, some game designers will take some influence from Rez. I couldn't imagine that at the time. I spilt my soul and passion into the game. But it took long years to build up confidence again."

Two years after the release of Rez, with Sega undergoing severe change as part of its merger with Sammy, Mizuguchi left the company to establish a new outfit, Q Entertainment. "I felt it was getting harder to do what I wanted to do. It was a very simple vision. I needed freedom, I wanted freedom, so I started a new company. I couldn't establish it myself, so I did it with some partners."

Q Entertainment's first game, the puzzle game Lumines that launched alongside Sony's new PSP handheld in 2005, would carry on where Mizuguchi left off at Sega. "It's the Rez experience bought to puzzles, but more casual, more easy to play. I got a lot of inspiration from the PSP itself, when I first heard about the technology - it's an interactive Walkman. Before that, PlayStation and Dreamcast, any consoles, they had no headphone jack. That was a bad condition for music. Even Rez, it's just from the TV speaker or a long cable headphone. PSP, it was like a dream machine for me. Everyone can play the game any time anywhere and any style with really good sound. What kind of game does everyone want to play? Very naturally I had the inspiration - it should be a puzzle game. Puzzles with music. Then we started experimenting, on PC first. We foresaw the spec of the hardware, and we made Lumines on PC. It was a small team again, about four or five over a year.

"I wanted the challenge of making a puzzle game. It's really simple and deep, and it's tough to make a new puzzle game. Even 10 years ago, everyone said the puzzle game is almost done, and there are no new ones. Everyone said that. But I wanted that challenge."

The challenge was met, and met well - Lumines remains one of the finest puzzle games since Alexey Pajitnov's Tetris, the template going on to power a series of games that peaked with 2012's Lumines Electronic Symphony. It was a commercial success, too, the sales in Europe and North America helping Q Entertainment forge a strong partnership with its publisher Ubisoft.

"They asked me what kind of project I'd like to create in the future," says Mizuguchi. "And I said I wanted to make a new Rez. A spiritual successor. I did some pitching documents and made a presentation. I met Yves [Guillemot], the CEO, and he made a very strong suggestion about using a new technology - it wasn't called Kinect just yet. But that atmosphere, the swell in the game industry at the time, I was like okay, if we play the game with Kinect, if you play Rez with Kinect, what kind of game could we make? That's when the project started."

Child of Eden made a spectacular debut at Ubisoft's E3 press conference in 2010, with Mizuguchi taking to the stage in white gloves, mirroring the performance he conducted to a smaller audience with the original Rez.

"I had two things in mind with Child of Eden. First, having more passion, and more emotion. With Rez, from the PS2, Dreamcast generation, it was impossible to put video images to good effect in. If we can use that kind of power, what kind of movement can we make, to have it more emotional? The other one is the physics. To make an atmosphere of synaesthesia, we needed a new kind of technical approach. If you put the sound data in some visual programme you get the particles spreading, the sounds change the graphics dynamically, that kind of thing. I wanted to make a much more dramatic experience compared with Rez."

With its soundtrack partly provided by Genki Rockets, Mizuguchi's own musical project, Child of Eden explicitly harks back to his days at university where he would make music videos for his friend's bands. "I wasn't conscious of that at the time, but naturally I tried to make that. Getting back to the basics, from the very start and from my time at junior high. When I was at junior high I had a big shock from the music videos. And I never changed," he laughs.

After Child of Eden, Mizuguchi took a break from game production, walking away from Q Entertainment as he took up a post at Keio University. "I also needed time to cool down my head after Child of Eden. I needed to think about the future. I needed to change gear. Now, 25 years after joining Sega, I want to keep my creativity going the next 20 years too. Maybe in the future, there's a future game. Or maybe this is the new form. I don't know. Making the new experience, what is the next canvas like that?"

Since our conversation in Japan, Mizuguchi has announced his return to games production after three years away with Enhance Games, a new studio whose first project is bringing Lumines and Meteos to mobiles in partnership with social and mobile game outfit Mobcast. After that, it seems he may be ready to return to other, familiar fare.

"I always felt Rez should be a trilogy. When I made the first Rez, I had to think about the next one. It's kind of my life's work. And then, all the time I'm thinking about that. I'm always thinking of the next Rez, the next Child of Eden."

As the technologies Mizuguchi first explored during his early years at Sega finally look to bear fruit, the possibilities have clearly rekindled the dreamy excitement that's powered so many of his projects. "To me, synaesthesia is a big thing. Watching Oculus Rift, it's like 20 years ago, 25 years ago, with the first virtual reality generation. All the time moving, like a spiral. 20 years ago, I couldn't imagine the future and what's next. I was so nervous. Now, I'm relaxed. It's very natural. Maybe in 2015 I will start again. I haven't decided exactly how just yet, but... I have a plan."