Man of Adventure: Ron Gilbert Profile

The adventure game guru explains the creative process behind Monkey Island, Deathspank, and why he won't make a serious game.

"Adventure games are about just stupid things," says Ron Gilbert, creator of Monkey Island, Maniac Mansion and Deathspank.

We're speaking about his past works in a meeting room at Double Fine's office where he's just revealed The Cave, a game about a talking, sentient cave. What could possibly be daft about that?

As it turns out, Gilbert not only admits adventure games are about stupid things. He revels in it, using the genre's core tenets as fodder for gags.

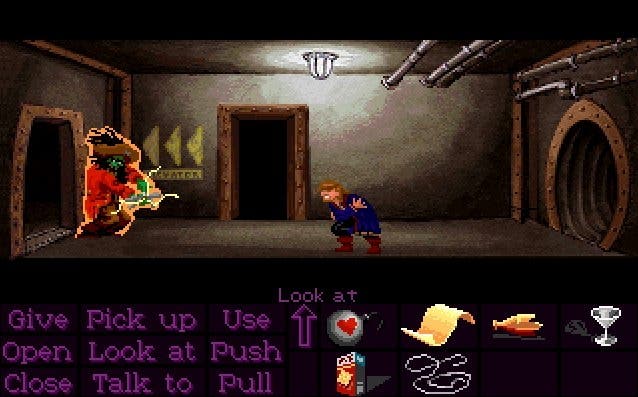

Take Guybrush Threepwood. The hero of his most well known series Monkey Island, Guybrush is a pirate because it's a profession that synchs up with the actions of an adventure game protagonist. "If you think about what adventure game characters do, they break into everybody's house and then they steal everything they can out of it and then stuff it down their pants and leave," explains Gilbert. "So it fit well with Guybrush being a pirate, because that's what pirates do as well."

Gilbert may specialise in one of gaming's most absurd genres, but that doesn't stop him from taking his work seriously. Looking back at Monkey Island, it was important to Gilbert that Guybrush's experience echoed that of the player's. It was a response to an experience with a Police Quest game, where Gilbert failed after not putting his gun in his locker.

"I've been trained by the LAPD and I don't know that I'm supposed to put my gun in my locker? It really occurred to me that what's happening in a game like Police Quest is you're taking an experience the player has and the experience the character has and they don't match."

So in Monkey Island he very carefully chose Guybrush's first words, "My name is Guybrush Threepwood and I want to be a pirate."

"I blame Doom," he pinpoints. "Because before Doom came out, games were a lot slower paced and people were a lot more interested in thinking and strategy."

"What that does is it helps the player identify with Guybrush, because Guybrush has no idea what he's doing and the gamer has just booted up this game wants to be a pirate and has no idea how. Guybrush learns at the same time as the player."

I tell Gilbert one thing I always admired about Guybrush was that despite his wimpy demeanor and general clumsiness, he was actually a good pirate. He does what he needs to do to get what he wants. He's overall a good guy, but he's still screwing people over left and right - something alluded to in Monkey Island 2's wanted poster that rattles off his various crimes like nailing a live man in a coffin.

Gilbert laughs at this, but he chalks up Guybrish's ill behaviours as a metaphor for how pirates and adventure game heroes act similarly. "He does cause bad thing to happen to people, but you do kind of wonder on some level 'does he really realise what he's doing? Does he totally understand how bad this is? I don't think that Guybrush has an evil bone in his body. He's just naive more than anything else."

That naivety is central to the game's fish out of water theme. "For me it's about a naive person being thrust into a complex situation that they have to fumble their way through," Gilbert explains. Just as Guybrush is new to the world of swashbuckling, the player is new to the world of insult swordfighting, voodoo recipes, and three-headed monkeys.

One day, while developing Monkey Island 2, he watched four-year-olds play its predecessor and found himself fascinated at their reaction to it. "There was no voice in the game back then. They couldn't read, so they had no idea what was happening in the story. But they loved walking these characters around. They loved clicking on doors and walking through them. They loved picking up stuff and seeing it appear. So they would just run around and have an absolute blast playing Monkey Island without any idea about what the story was or what they were trying to do."

"So I kind of got this idea. What if I made adventure games for them?' Where the stories were simple, the puzzles were simple, and everything was voiced so they didn't need to read." This was set the seed in Gilbert's mind to start his own company, Humongous Entertainment where he made such titles as Freddi Fish and Putt-Putt.

Following this move, Gilbert seemed to have disappeared from the public eye for a decade as the genre he was associated with went out of vogue. I ask Gilbert why he thinks adventure games by and large went out of fashion. First off, he dispels this myth. "Adventure games never really died. They kept selling the same number of units that they've always sold. The problem is that everything else was selling more units. They reached more of this stagnation rather than a dip."

And why did everything else gain popularity? "I blame Doom," he pinpoints. "Because before Doom came out, games were a lot slower paced and people were a lot more interested in thinking and strategy." He cites games like Civilization and Ultima as examples along with the point-and-click adventure. "These are very kind of slow moving games and you just sort of absorb yourself into it. You just kind of enjoy the moment of being in the game."

"And then Doom came out... it was visceral, and it was fast, and you shot stuff, and gibs flew off of everything. And it just kind of flipped a lot of people's thinking a little bit, and also attracted a much bigger audience into games. With the adventure game people stayed, they never left. But there were all these other people that kind of came and things like Doom just sort of started to dominate."

This shift in gaming culture lead to Gilbert's most recent success, DeathSpank, an action/adventure/RPG that satirises the industry.

"He [Deathspank] was always kind of envisioned to be a satire of games. He is this character with this big bravado and every situation for him is solvable with a sword," Gilbert explains. He notes that most action game are like this - where instead of behaving realistically, you're tasked with charging into battle guns a-blazing. "That's really what games make gamers do. They make them just hit everything with their head over and over again until they break through, and so with Deathspank I wanted a character like that."

"I don't know that I could make a completely serious game. I really start thinking about them more as serious stories, and then let those stories move into the more comedic areas that they need to. I don't think I could ever not be putting funny stuff into games."

Much like Guybrush, Deathspank is naïve - only he's more of a hitter than a thinker. "He's single-minded. He has a real soul. He does kind of care. He doesn't just wantonly go out and slaughter people. But he just kind of slaughters everybody in his single-minded vision of getting this thing done that he needs to do. He doesn't really think about all the carnage that's happening behind him. To me, he was just a satire of what videogames are like."

Gilbert then points out that Deathspank's purple thong was a critique of the rampant sexism in the industry. "That was really a statement about how I saw videogames and how they depict women." He explains that your typical fantasy game cover will have a man wearing what looks like a stove, while the woman is brandishing swords in a bikini. "It's like 'seriously?' She's not ready to go into battle wearing that. There's this sort of sexism that I really saw with women in combat games being portrayed as. So I wanted to do that to Deathspank. He wears the thong."

Despite the generally silly humour, Gilbert's games still deal with serious themes. His upcoming game, The Cave, is about a group of strangers in a supernatural cavern that teaches each character something about themselves and explores some sort of darkness in each of their souls. It's still got all the ridiculous humour one expects from a Ron Gilbert game with a meathead knight, lackadaisical hillbilly, and creepy orphan twins, but thematically it seems much darker than anything else in Gilbert's repertoire.

"Have you ever considered making an entirely serious game?" I ask.

"I don't know that I could make a completely serious game," he replies. "I really start thinking about them more as serious stories, and then let those stories move into the more comedic areas that they need to. I don't think I could ever not be putting funny stuff into games."

I suggest this is because the medium is inherently abstract and silly. Characters touch a first aid kit and all of a sudden they're better, and NPCs never seem to be able to take care of themselves.

"I think that's doubly true for adventure games," Gilbert explains. "You're using weird objects with weird combinations of things. You're stuffing your entire inventory down your pants. You've got these weird puzzles where it's like you need a pencil, but there's only one friggin' pencil on this entire city... If you can play that up with comedy, if you can make fun of that, people are willing to suspend their disbelief about that stuff. That's why I think adventure games in particular really need to be funny."

So maybe adventure games are stupid, but thankfully we live in a world that loves stupid. The genre is resurfacing with Kickstarters for Double Fine Adventure, Leisure Suit Larry, Tex Murphy, the Space Quest creators' SpaceVenture and Jane Jensen's Moebius all getting funded.

Why the resurgence? "The reason that's starting to change is because everybody plays games now," Gilbert explains. "Games are not this kind of thing that's relegated to this niche audience of these nerd game players, because of things like iOS and the consoles in everyone's living room."

He also attributed this to gamers wanting to share the genre they grew up on with their kids. "People are just getting older. My dad did not play videogames when he was a kid, so there's nothing for me to learn from my parents about videogames. But we have adults who have families and they gamed when they were kids and a lot of them still game." He suggests that parents will want to share this pastime with their offspring in a way not possible in his day.

Hearing Gilbert's nonchalant admittance that his life's work is about stupid stuff, I'm reminded of a quote by Roger Ebert; "It's not what a movie is about, but how it's about it." It's a rule that applies to games just as much. So yes, adventure games are about stupid things - puzzles based on puns, gullible shopkeepers that fall for the same trick indefinitely, monkeys disguised as brides - but that doesn't mean they can't still be brilliant.