Rewriting history

Replay author Tristan Donovan on why games began with the atomic bomb.

That's right – the ENIAC was the first programmable computer.

Clearly you could go back further to early games, but that seemed to be going back too far and it would require too much extraneous explanation. You'd need four chapters on the history of board games and of pinball games. I just needed to narrow it down.

The background to the Cold War was quite important to gaming history, in terms of the types of themes people picked up on like the whole obsession with the space race and games like SpaceWar! and Missile Command, and then also from a technological standpoint.

A lot of technology emerged from the Cold War arms race. Things like the microprocessor and other things, which came about in part due to military funding. This kind of historical context matters.

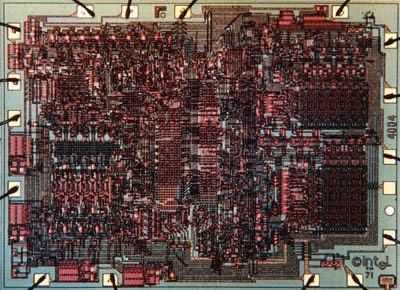

It's useful to explain how computers started. One of the things I didn't realise until I started doing the book, for example, is that until the mid 1970s, games weren't made using microprocessors or programming. It was hardware.

People built actual circuits to make games, which is why emulators tend to have difficulty with things before then: there's no code, it's all hardwired. So having a little bit of background on how computers evolved was quite useful.

I came quite late to deciding what to begin with but once I knew all this stuff, it made sense to go back to the 1940s. Where it actually begins is a topic people will argue about forever. I don't think there was a first videogame: it evolved.

Ralph Baer will disagree with me - he made the first one. Nolan Bushnell, he might say he did too, but it's a never-ending debate. I do think you can see the origins back in the 1940s, though.

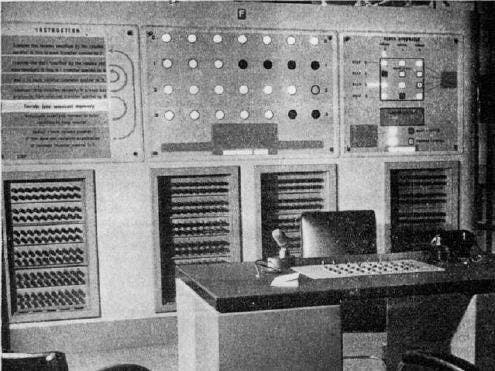

NIMROD came out of the Festival of Britain, which was this big post-war project to lift the spirits of Britain after the Second World War. London was still rubble and the country was still on rations, so you had this very austere start to the early 1950s. The Festival was to say, "Look, there's a new technological future and a new cultural future, and tomorrow's going to be so much better than today!"

One of the parts of that was computers. So NIMROD was created by John Bennett. He worked for a company that was asked to create a computer exhibit. People hadn't had any contact with computers and didn't know what they did, so he made a very simple game called NIM that this computer could play to introduce people to the machines. He wanted to get across that computers do maths, basically.

People thought it was fun and a little bit scary, as the machine was nine feet tall and towered over everyone. So there was this period in the 1950s where people made games, but they were always to explain what the machines could do.

They weren't for fun. They were made for artificial intelligence research or something of a similar nature. People didn't like the idea of using this technology for something frivolous.

I did have a bit in the book about games becoming art but I ditched it in the end, as it was starting to become my opinion rather than history. That said, there's this idea Wagner has, called 'gesamtkunstwerk'. It's basically a concept he had about opera being the art of all arts: it brings together costume design, singing, music, writing etc.

So I had this probably very pretentious ending in mind where I was declaring that videogames had become that: a summation of all these arts, like animation, camerawork, play, storytelling.

Obviously movies can say they bring a lot of that together, but games arguably have a better case. So that was the over-riding theme I had, that we were moving away from the ten-cents-for-30-seconds-of-entertainment idea.

There's also theme of things becoming more complex, and of the rise of big business and this multi-billion pound industry we're in. You could argue that has sucked all the creativity out of games, but things like the emergence of the indie games scene right at the end change that - they're really a response to the problem of the scale of the industry exploding outwards.