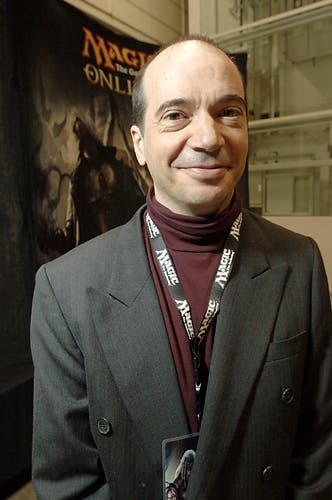

Richard Garfield: King of the cards

A rare meeting with Magic's reclusive creator.

Richard Garfield doesn't remember much about the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. It was a bloody conflict, which caused the displacement of millions of refugees and presented an ongoing threat of violence to his family, who had moved to the country for Garfield's father's job as an architect.

"As a child, I never felt threatened," he says. "But I think my parents were pretty worried. There were executions occurring and a lot of violence.

"We were pawns in a game being played. The government wouldn't let us go, then the United States' Government demanded we were let go, and so on. It was hectic."

Reaching Nepal after the battlefield of Bangladesh was a welcome move. Although Garfield was only eight at the time, he has fond memories of the colourful country.

"Nepal was wonderful. A beautiful landscape, and the people were wonderful. We had this interesting mixture of religions and cultures."

"I believe it had a large effect on me, but it's always hard to tell," he says. "I feel like the exposure to so many different cultures and attitudes made me more empathetic, in a way, which ties back to game design."

"Good game design is empathetic."

"Good game design is empathetic."

In gaming circles, Garfield's name carries the weight of a dignitary. Although credited with helping create several successful card and board games, Garfield is best known for birthing Magic: The Gathering, the world's first collectible card game.

If it isn't the biggest CCG, it certainly comes close. Hasbro, the entertainment giant which owns Magic's publisher, Wizards of the Coast, credits the cards as one of the main reasons its games division is growing. Grand Prix tournaments give out hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money every year, and there is an active buyers and sellers' market. Rare cards fetch thousands. Running commentary of matches has even shown up on ESPN.

Garfield's contributions go even further than the game - he effectively created the genre: his name is on a 1997 patent covering the "trading card game method of play".

Yet Garfield has little to do with Magic anymore. Although he joined Wizards of the Coast as a designer in the 1990s, he left several years ago and contributes to other design projects. He conducts brief interviews from to time, but is hardly a public figure. His contact details are elusive, and Wizards of the Coast wasn't able to pass through press requests.

"I was, and am introverted, although not in a debilitating way," he says, in an effort to explain his aversion of spotlight.

"But I believe that's part of what the appeal of games were to me. Games provide you a set of rules for interacting with people, and I pride myself to this day on no matter who is visiting, or what company is around, I can find a game that will entertain everybody."

Garfield found his spark for play in Dungeons and Dragons, which he still calls "the most original game that's ever been made".

"It wasn't about winning or losing, it was about creating an experience, and it broke my expectations about how long a game can be," he says.

"Games really seemed like this field where anything was possible to me. I still feel like there could be schools in which the entire curriculum is taught by games.

"It's very interesting to me that games have been such a huge part of human culture but so little is known about them. We know the Romans played games, but they didn't write about them in the same way they wrote about literature or public events."

The story of Magic's creation is well known, and so is Garfield's experience and knowledge of mathematics - he holds a PhD in the field. But less universal is his reasoning behind such a hands-off approach.

"I stepped back, and that was a very conscious decision based on, among other things, that Magic was going to be bigger than one person could provide."

"I did not want to be the creator that kept such a tight control on his creation that it couldn't reach its potential. I was more interested early on in getting people trained on how to expand the game."

And Magic has certainly grown. A revolving team of designers work on new expansion themes for each September, followed by two smaller expansions the following year before starting again. Each set comes with new mechanics and nuances - the Magic rulebook contains thousands of clauses and sub-clauses.

Although Garfield has popped up on a few expansions as a designer - the last being in 2011 - he stays out of the game. He doesn't even buy every set.

This is how Garfield likes to work in general - as a facilitator for a medium, rather than an assistant in its expansion. It's also why he likes to work alone.

"I'm very good at receiving feedback, and I don't generally get too invested in a particular idea. That keeps me broad," he says.

"I'm poor at working with people in the creative process if there is somebody working with me and they keep shutting me down. I can't think creatively unless I'm working on my own."

Garfield's introversion is reflected even in our hour-long phone conversation. Softly spoken and articulate, he will pause to answer even the most simple question, as if giving them the most strategic priority possible. At one point, I had to ask if he was still on the phone - he had gone quiet for so long I assumed the line dropped.

For as well-known as Garfield's name is in certain circles, he says the fame associated with Magic is the "good kind".

"I can be known at a convention, but once I walk away no one knows who I am," he says. "Outside of it I live pretty quietly and privately. If I couldn't turn it off I would want to perhaps go back to a quieter time."

Although Garfield's soft-spoken nature has never interrupted his work life, he admits there have been clashes.

"I've been in situations many times where I start working on a game with somebody, and they're just not contributing, they're not doing anything. I can't work that way. I need to lay a gentle framework by myself for 12 hours or whatever, then meet and collaborate then."

Taking inspiration from his father, Garfield calls himself an architect. He likes to build blueprints, then hand them to engineers who build the rest by themselves.

"I like putting the frame work of a game by myself. Afterwards, I'm good at working with people about the particulars."

"Whenever I play a game which moves me in some way, I try to figure out what's causing that."

This process gives him a break from controlling all corners, but more importantly, it allows him to pursue a "diverse taste in everything", both within the games industry and outside of it. Garfield has worked several game projects, including board games like King of Tokyo, to other CCGs like Star Wars and the cyberpunk-themed Netrunner. Some are more successful than others (Netrunner particularly is enjoying new life in a re-release by Fantasy Flight Games - and Garfield approves), but they fulfil Garfield's criteria of at least being interesting to him.

But this is actually something he pinpoints as a disadvantage of how large Magic has become - to be good at the game, players need to spend a lot of time studying how to play, which robs them of the opportunity to try other games.

"If a collectible card game is going to be successful, then it's going to swallow the player's time," he says.

"And if I have a disappointment with all of this, it's that followers of trading card games dedicate themselves to one game rather than a variety of games."

Of course, dabbling in other games is expensive. Keeping up with competitive play in Magic requires constant purchases of new packs, which are released every few months. Competitive decks, which are copied among tournament players, can cost several hundred dollars and always change.

It's a barrier to entry Garfield acknowledges, although says some people making that particular claim "don't tend to understand how they're in charge of their own game environment and not the company".

"I don't keep up with Magic, but I still play it. Magic itself scales very well to what investment you like," he says.

"You can put in a little or a lot."

"Where the criticism becomes true is where friends are putting in a lot, but one person may not want to. You have to modify play patterns, and they can be shut out. I sympathise with that."

This type of concern for others and prioritising the experience of a game, not the game itself, is what Garfield believes is his holy grail as a designer.

"Whenever I play a game which moves me in some way, I try to figure out what's causing that," he says. Magic allows people to put themselves in the role of the game designer in a way reminiscent of Dungeons and Dragons, says Garfield. The randomness of using a deck forces the player to carefully choose which cards they're going to use at that point in time; they're participating in the design process. It's empowering, often overwhelming and judging by the game's success, hopelessly addictive.

Winning or losing is just a by-product of something better, he says. A shared experience which people can treasure. Playing more games isn't just fun, according to Garfield - it can make us better people.

"Games are a wonderful, structured way of interacting," he says, "which can bridge all sorts of personalities."