The big Larian interview: Swen Vincke on industry woes, optimism, and life after Baldur's Gate 3

"When you push too hard, it breaks."

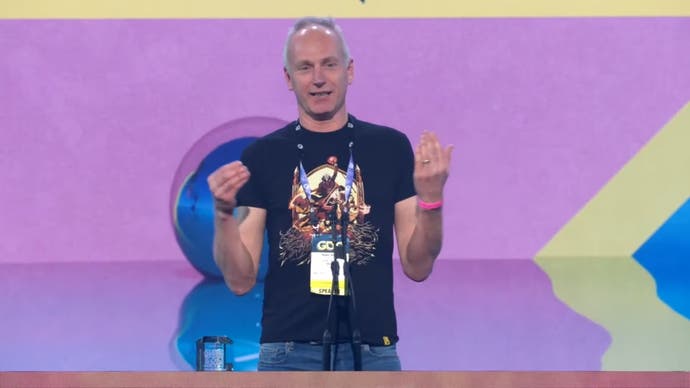

"Greed has been fucking this whole thing up for so long, since I started," said Swen Vincke, founder and head of Baldur's Gate 3 developer Larian, while collecting Game Developers' Choice award for Best Narrative last week. "I've been fighting publishers my entire life and I keep on seeing the same, same, same mistakes over, and over and over."

Vincke's speech - an impromptu one, he says - quickly took off, attracting an outpouring of support from developers on social media and echoing the frustration and, at times, outright anger of other developers at those awards. But alongside the understandable sense of indignation at the seemingly endless wave of layoffs hitting the industry over the past year, Vincke's speech - and the reaction - also highlighted something broader: video games are having a moment of introspection.

Amongst all that - and after the extraordinary success of Baldur's Gate 3 - Larian has become something of a beacon for the industry. A rare case of not only a fully independent studio but a large one, with hundreds of employees around the world, Larian has sustained that size while producing a game that people genuinely love. Baldur's Gate 3 swept awards and dominated headlines in a year that also featured a new Zelda game, a new Mario, and new RPGs from Blizzard and Bethesda, but it's also become a form of living proof for those who'd argue there is another way - and that this way is the path through the industry's problems.

Talking to Eurogamer at the end of last week, Vincke elaborated further on this, but also on some of the other solutions thrown up as potential panaceas to game development's ills, like generative AI and Ubisoft's "NEO NPCs" - announced earlier on at the conference.

Vincke also elaborated on a few eye-catching points from his GDC talk, where he first announced Larian's next game won't be Baldur's Gate 4, DLC, or anything in the D&D universe. That includes his claim that Larian's initial partnership with Google Stadia was "a really stupid deal, we shouldn't have done it," or the balance between listening to players and fanservice, after the "disaster" of Baldur's Gate 3 dipping below 75 percent positive Steam reviews during Early Access. (The studio was "essentially doing games-as-a-service" development to merely sustain the first act while it was live, he said.) He also gives a little more detail on the changes to ever-popular high elf Astarion, who was in fact first a tiefling, before his species was eventually swapped, and mentioned both the "different tone, style, way of doing it" for the studio's next game, as well as early hopes for where it might launch.

Eurogamer: It feels like there's a kind of fire in the belly of developers at the moment, here at GDC and I suspect from developers everywhere, for obvious reasons - I can probably guess your answer, but I wanted to know why you feel that is, and what exactly that's directed at?

Swen Vincke: I think this is a frustration that developers have had forever, alright, because we've always been dependent on third parties. I mean, like, when I started out as an industry, one of the first publishers I met told me with a smile - a smirk really, "Luckily for us, this industry is driven by idealism." What he really meant is, "This is how we profit". And it's true. It's literally true. I mean, like a lot of us are idealists that like to entertain people. This is why we became developers, alright - and so it's very easy to abuse. So you see a lot of that. And so none of us want to be economy designers. We don't want our games to be milked out or concepts to be milked out. We just want to make new things, and entertain people. And so I think that's something that's shared across [the industry]. Regardless of which development platform you are, I think that's something that's shared, because ultimately, you just want to entertain players.

And so what's happening as a result of that now is that some of those models have been pushed too far, in pursuit of profits - rapid profits - pursuit of bonuses. And then, as a result of that, you saw a whole bunch of people being fired, which is predictable, because we've seen it over and over and over. So there's a lot of anger about that, right? I mean, that's just the way it is. And there's a big disconnect still, between certain - not everybody - but certainly between certain people in management positions and the actual developers themselves.

I'm interested in how that feeds into the approach to making games themselves. In your talk, you talked about your "KPI" being "fun". I very much enjoy hearing someone say that, but also wondered how possible it was for most studios. I look at Cyberpunk 2077 developer CDPR as a really good example, where they're still technically independent, but they're also a public company. So they've got this weird thing where while they don't necessarily have a publisher to deal with, they've still got to anwer to the interests of, say, shareholders. So I'm curious to know if you feel it's that simple - to just make something fun and the rest will follow?

Vincke: No, because making games is hard. I mean, it's a complex business. I mean, like it is a business. And so, you do need to make profits to be able to continue making games, or at least break even, and so if you're not going to manage that, then you're not going to be able to make new games, so. So there's nothing wrong with that. I think the - my problem really is with pushing it so hard in this, for sake of exponential growth, which never works, that's my problem. I don't have a problem with linear growth, or with people trying to be able to do bigger and bigger things, which, that's what we're doing. So it's not that simple. I mean, but it's, I think, you know, the games industry is a very special thing. It's like, it's special but it's like music, and it's like books, and it's like movies. And so you have people that really want to make something that they care about. And then you have people that just say, well, we just want to have more profit out of it. And the - even that is okay, as long as you don't just push it too hard, because when you push it too hard, it breaks. Because it's such a fragile thing to make. It is.

We are one of the few industries where you can't repeat the formula from the past for a long time, because everybody expects us to innovate technologically - and also, we are the intersection between technology and art. And that makes it much more complex. And then a whole bunch of other industries like in TV, they can keep on using the same medium for a long time, right? They can innovate, but they don't have to innovate at the speed we have to do it, right? And if you innovate at such breakneck speeds, as we have to do it, and then you start pushing on top of it, you break things. And there's always gonna be human consequences, when things break.

Another topic that's come up sporadically around this is the longevity of development staff. I look at the talks given by the likes of Nintendo at GDC (on Tears of the Kingdom and Super Mario Bros. Wonder) and the people who have given those talks are what you would call senior developers - people who've been doing this for 20-plus years, many of them at the same place. The impact that continuous experience has on the games they make feels obvious. But everywhere seems to be struggling to keep hold of its veterans. Larian seems like one of the few remaining examples where its senior staff have been there from the off, so how can developers get better at building and then keeping hold of experience like that?

Vincke: Well, I mean - by not firing them?! [laughs] That's really straightforward. I mean, whenever you lose a senior developer - it happens, there's a variety of reasons, people move on, they have partners that move elsewhere - so it's not that you can maintain all your seniority forever. But you can typically maintain a good portion of it by treating them with respect. So that's really the thing. I don't understand - I see companies, like with the current layoffs, when I hear who's being fired I said "What?! That doesn't make any sense." Because that person is like a beacon of knowledge within that company. And it's what shows that disconnect I was telling you about, because I know it's being looked at in an Excel file, right, and the person that makes a decision with that Excel file does not understand what they just lost. And it's going to cost them way more, long term - they just don't realise it yet. But it will cost them a lot.

I'll give you an example: I heard of a group of technical artists being fired. I can tell you, I'm a developer: if you fire your Technical Artist, you're an idiot. Because they define your entire pipeline, which is going to define your cost of your assets. They can define so many things and they know your games - especially if the senior ones, it really doesn't make any sense. Anyway, we're hiring them to come work for us.

It feels like developers have been looking at you, and at Larian generally, almost for guidance here, because you've been critically successful and commercially successful, and after the speech earlier in the week as well. Do you feel a consciousness of that?

Vincke: I actually didn't plan, originally, to say anything - because I have a lot of thoughts, and they're very nuanced, and these forums are usually not, necessarily, the right place to be nuanced about things. But I heard the [previous] speeches, and I had just had a conversation with my old agent. And so we were talking about the state of the industry and I asked him, "How is it going?", because he represents a lot of developers, so he has instant knowledge about what the future in a couple of years is gonna look like because he sees what's being invested, what's not being invested.

And he told me: "Well, it's actually going better than I expected." I said, "Well, that's funny…" He says, "Well, no, it's also a waste." And so I asked him, "What do you mean?" And he said, "Well I mean, the cycle is just repeating - they fired them all. So now they're all looking for co-developers. So by the end of the year, they will be trying to hire again, because they'll realise they have to make games and they have to tell something to their shareholders." [laughs]

He's very fatalistic about it, because that's his job. But I mean, he's very knowledgeable about the industry, and he's right! It's always like this, and so my thing was really: we could probably skip this step, alright? By not having to pursue that aggressive growth.

Related, something you talked about in your talk, was the growth of employees that you have. I tried to scribble it down quickly. I think it was something like just under 50 in 2014. And now it's around the 475 mark -

Vincke: 470, yeah.

Right - so does that feel sustainable? Because it's a massive amount of growth. And have you been consciously mindful in mass hiring, that you're like, "We can keep these jobs even if you don't release the game for, say, five years"?

Vincke: So, we built multiple fallback positions in case it was going to go wrong - before we started doing this. I have a minority investment, so I had that in my back pocket in case it was going to go wrong. So this was my baseline, otherwise I wasn't going to take the risks that we took with Baldur's Gate 3, because it was too much of a risk. So that's actually also why I did it, or part of the reasons I did it. So there's that.

We also knew what our sales were, so Early Access gave us a really good indicator of where we were going to be going. So we can forecast, more or less, and function - if we don't fuck up too much, there's always a risk involved, right? I'm never gonna say there's no risk - but you can forecast more or less where you're gonna land, based on interest, based on Early Access sales. So we could see where we are. And so we're good for quite a number of years with where we are right now.

Is there an inherent aspect of video game development that requires you to have to lay people off at some point? Say if you have to staff up for the final push or a specific part of the process - how do you navigate that, or does it not have to be that way?

Vincke: It happens, for sure. When things are starting to run late, what can you do - you can outsource? But that's hard, because you have to onboard the outsourcers. You can hire new people, but then you have to onboard them also - but you can then offer them a contract job, or a permanent job. If you give them a contract job, you're not going to have the problem after release, so we have many contractors. But if you're gonna give them a permanent job, then you have to make sure that you have work afterwards. Now, typically, it takes a long time to onboard somebody in a game developer, so you prefer to give them a full time job, so that you can keep on working with them afterwards. But that doesn't necessarily have to be the case. It really depends on what your plans for afterwards are.

Coming more to Baldur's Gate specifically, but still on the topic of your talk - you mentioned the Stadia deal being "really stupid" - why was that? I remembered from a Larian interview I had with the first preview event you did back in 2020, that it was seen as a positive then, because it was a decent up-front investment.

Vincke: I thought the technology, the promise of the technology and what we saw before - so two years before it being revealed - was great. So I said, "If that works, I want to be on board". So I don't regret that part. The bit that I regretted is that I underestimated what an impact it was going to have on our own development itself. Because we had to essentially optimise for console ahead of time, and that [is what] I didn't realise fully, because we just finished Divinity: Original Sin 2 on console. So I said, "Hey, we can do this!" But this was before I actually understood exactly how far we were gonna go in the refactoring of our engine. And so that put the engineers under stress. That was the bad part about it. If that wouldn't have been the case, then I probably would have said this was a great deal.

I'm curious about the issues with consoles - are you going to change your approach with the next game? It's a long way out of course, but does it make you reconsider how you go about launching a very large, ambitious game in the future, in terms of saying "Maybe we'll prioritise PC first and give us time to think about consoles?" In your talk you mentioned bringing just the PC launch forward was what made that release ahead of Starfield possible. Does it make you question coming to consoles at all?

Vincke: Well, I think that we need to have a console on each desk while we're developing, because it does take a long time to get everything working. The benefit of working for console is also that the minimum specs on PC are low [as a result], which is good for your sales in general. So you want to achieve that.

Are we going to try out multi-platform releases? We would like to be cross-platform on day one. That, I think, is the best for the game, in terms of its commercial potential, but we will certainly mitigate it against what the development cost on the development side itself will be. So it really depends. It's very hard for me to tell you an answer, or definite answer, right now because it's too far out. But I did learn that whatever we release needs to be really good. Certainly for the type of games that we're making, and so if there's something that jeopardises it, I'll probably be erring on the side of caution.

Another thing that came up, in a conversation with another developer here, was this idea about the engine being secretly a major factor in a game like Baldur's Gate 3's success, because it was the same one you'd been using before - the idea being that it makes your life a lot easier and gives you more freedom to do what you want. Is that right?

Vincke: Yes.

What I kind of gleaned from your talk was that you had to do a lot of reconfiguring of that engine though, because the game is still very different from Divinity…

Vincke: Yeah, there's a reason why we're not switching to Unreal, for instance. Because we think the strengths of having your own engine is way, way higher than being able to switch to somebody else's engine. We worked with the Gamebryo engine, which was the same engine that Oblivion had, back in the day. So we learned there that the engine's roadmap is not necessarily your roadmap. And so if you work on your own engine, there's a price to pay for sure. And sometimes a heavy price. But you will always benefit from it. So if you can manage an engine team, and support it, I think that's beneficial to your game. And so the fact that we are working on the same engine already, since 2010, gives us a lot of benefits, that's for sure.

You mentioned the new game briefly - the thing that I picked up from one of your other chats was that it would "dwarf" BG3...

Vincke: Did I say that, really like that? I think that I've been misquoted on this.

Oh really?

Vincke: Yeah, no. So that's a bit - I saw that pass by and said, like "I need to check what I actually said". So either [it was] because I was heavily jetlagged, so either I said it wrongly...

So it's not the very big RPG that will dwarf them all, that we're making now. I mean, we have a couple of - we have two games that we want to make, and we actually intended on making after BG3, so we're just back on that track now. They're big and ambitious, that's for sure. But I mean, I think scope wise, BG3 is probably already good enough!

I was going to say, yeah, it didn't sound like you were talking in that talk going: Oh, yeah, we definitely need to make something even bigger…

Vincke: That's why I'm surprised…

The specific wording that you had in the talk was like, we're gonna do "something new." I wanted to see if you could clarify whether that meant a new IP, or just not D&D.

Vincke: Well it's not D&D. So we're - new in the sense that it is different from the things that we've done before. Still familiar enough, but different. I mean, like: tone, style, way of doing it, are for us certainly new. And I think very appealing. I would love to talk about it already because I'm excited about it but I can't say more. But it's new in that sense.

One of the things you've talked about a few times was this notion of listening to players. And I'm really curious about this, partly because I look after reviews and so the topic comes up a lot in terms of, I suppose, "artistic intention". So how do you draw the line between listening to feedback, especially with an Early Access game and where the Steam user reviews are so essential to your success, versus losing your own vision? Or veering into fanservice? I'm thinking of things like Mass Effect 3's revised ending…

Vincke: It's a good question. So what I tend to do is, when I see a lot of vocality around something (I don't even know if that's a word vocality, but I guess you understand… [laughs]) is that I'm going to check with the playtesters. Or I'm gonna check with our designers. And we'll have a discussion about it.

We'll also look at the analytics that we get - like, does the qualitative voicing represent the entire community? Or is it just a very small portion of it? So we'll discuss it from that point of view. And then if we think it's big enough of an issue, then we'll start addressing it. It doesn't mean that we're doing what the community wants, because sometimes they're just saying it's a symptom, it's not necessarily - the solution is not necessarily what they propose. What we're going to try to alleviate, especially, [is] if what they're talking about does not match what we intended.

So if a feeling that they're getting does not match what we intended them to have, then we will adapt, but we're not slavishly going to follow whatever the community says either, because that would probably not end anyway - we would never stop working on the game! So it's a balance, really. There's a lot of intuition involved. There's some analytics involved - those are hard numbers. So [for example] if everybody's saying it's too hard, but we see that only 2% dies, then it's not too hard, right?

On the topic of difficulty, you mentioned you intentionally wanted to throw people into it and not hit them with 500 pages of D&D rules, but were you concerned about onboarding at first?

Vincke: Yes. For a long time, we worked really hard on it, the balance - because indeed, we couldn't teach you the entire handbook so we had to throw you in, and we needed to make sure that you wanted to continue sufficiently so that you would start learning the things that you would learn. And so we did a lot of experiments with that. It was a very, very, very complicated and very fine line to walk.

Is there something that you would do differently for the next game?

Vincke: Not have such complicated rules. [laughs]

That makes sense! A gear shift, but there was a mention of AI in your talk, I think it was a question actually from the audience about generative AI. I was at the Ubisoft event where they unveiled these -

Vincke: The NPCs?

Yeah. Which was very odd - not necessarily my belief of what the future looks like. I wondered whether you feel like that is the panacea that some people want it to be, for the industry right now? It feels like there's two things going on - a little boost to efficiency that's happening already, and a big generative "revolution" that's yet to materialise…

Vincke: Well, I can only tell you about how we are looking at it. So, we certainly don't see it as a replacement for developers. But we do see it as something that allows us to do more stuff. So there are things like - I talked about the quantity of cinematic notes that we had to handle [in the GDC talk]? We had this thing for the one-liner NPCs. There's not a lot of creative accomplishment to be had by putting the camera on a singular NPC that only has a couple of notes - I'm very happy for AI to handle that. We're not going to do that for the very complicated scenes because there, the artistry is going to shine through.

So there's uses for it. Where I see use it for is - but this is really not there yet - is to augment the reactivity and dialogues. So you would, for instance, have writers and a scripter and cinematic designer, and everybody that goes with it, you would have them make their entire scene, and then you would augment some reactivity into it, to things that you've done before. So it is about, for instance, let's say it's a guard talking about a murderer that is free in the city. We don't have to foresee all of the possible people that you could have killed in the NPC['s lines], but they could be talking about that, right? And say if it's like multiple people, they could say, "Oh my god!" and it's like, literally a serial killer.

And then if you arrive there as a player, that would feel good, right? But you would still lace that into your overall web. So I do see it as an additional tool that you can put on top of the things that are in the game. And we're certainly doing experiments with that. But as I said, it's still far from being usable in that sense. But I can imagine, in the same breath, that you make a science fiction game, where you say, well, there's robots walking around, so they'll talk like robots. Okay, well, that makes sense.

One of the last things I wanted to ask you about was the fact there's a lot of consternation or worry in the industry, especially here at GDC, although it depends who you ask. For younger people or new developers, or people with startups, or any developer or person who's in a position to make important decisions right now, I wonder if - since there's been this attention on Larian, its success, and how the studio's been run - you had some advice on how you feel the industry should navigate this.

Vincke: Well it's always been tough. I mean, this has never been an easy industry to get into. The period that we're going through right now reminds me incredibly [strongly] of 2009, which was really a dark period in the industry - but also for the world economy as a whole, really. Plenty of studios popped up, plenty of them very successful, we took our fate in our own hands. So there's opportunity to be had, so I think it's about looking for those. That's the way that we're going to come through, and those developers that will figure it out, they're going to be hiring.

Making games is so hard that I can't believe it - so I'm optimistic about this as well. I think that making it is so hard, the talent is going to be needed. And so there might be moments - and currently it looks grim - but I'm sure that developers will come knocking and hire again to be able to make games. Because they're getting so complex to make, that you really need a lot of expertise - and that expertise, you're not just going to find it like that. Especially with the ones that have experience.

The last thing I wanted to ask you is a bit more light-hearted. I'm sure a lot of people are wondering after the news from your talk that Astarion was once a tiefling, if you could explain why the team changed his species?

Vincke: Well, the thing is that I don't actually remember! [laughs] Because I was surprised myself - I'd forgotten about it. I do remember there was a matrix where we said, "Okay, well, let's represent every single species, so that there's diversity across the different origins."

But then he didn't really hit it off as a tiefling. So that's how he became an elf. But I don't exactly remember the conversation around it, or how it happened. The thing is, it's also that the roster of companions was much larger originally [in fact one key Baldur's Gate 3 villain was once recruitable]. So he just had to probably be the checkbox tiefling. This was before we knew who he was, so it's not abnormal that things like that change. Lots of characters have changed, because at some point, there was a balancing pass on diversity, and then we said "Oh there's just too many of them, so let's make those [into] that, so that changes also…" It's very "developer". [laughs]