The hope and despair of A Light In Chorus

On turning the Golden Record into a video game.

If you have any interest in the problem of accessibility in art, you owe it to yourself to consider the Golden Record. A gold-plated phonograph disc packed full of Earthly imagery and audio, from Peruvian wedding songs through genetic formulae to pictures of US supermarkets, it was launched into space aboard the Voyager probes in the late Seventies. You could call it "a message in a bottle" about Earth to hypothetical star-faring civilisations, in the words of leonine celebrity scientist Carl Sagan. You could compare it, a little less kindly, to the "cabinets of curiosities" owned by European oligarchs and aristocrats during the Renaissance - Earth's riches bagged and tagged by the reigning superpower for extraterrestrial appreciation. But the more appropriate term, perhaps, is "puzzle".

While the Record's creators understood that theirs was largely a symbolic gesture, given the astronomically low odds of each Voyager probe's recovery, they engaged whole-heartedly with the idea that it would need to be deciphered by another species, millennia from now. What form might this species take? And how to explain something as vast, ornate and gruesome as human history to a life-form that, say, perceives the world entirely as scent? What at first seems a question of representative curation warps into something uncannily like a problem of game design, of interface and signposting, amassing common ground between creator and audience. The Record's architects speculate plausibly that maths can serve as a universal language, because two plus two will always equal four wherever you go in the cosmos, but what about a photograph of a man pouring water into his mouth? What if the confused recipients decoded the image the wrong way up and mistook the jug for a living entity, drinking from the man?

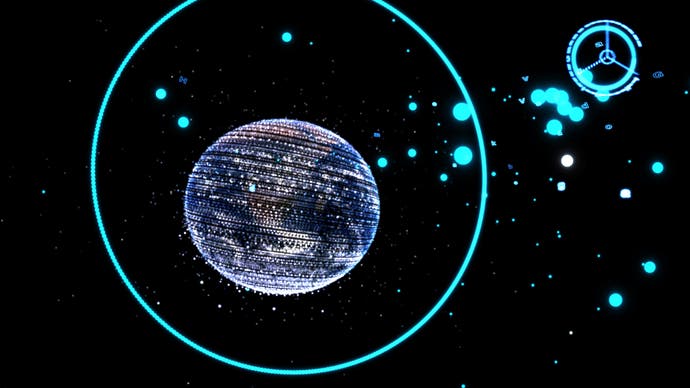

It's a challenge to send the most battle-hardened of UI departments galloping for the exit. "It's one thing to have it all in a book with [the images] all laid out on these pages, but if you're experiencing this one thing at a time, even if you do it sequentially, it's an odd story," observes the designer Eliott Johnson, one half of youthful UK studio Broken Fence Games. "The connective tissue between these pictures is non-existent." The Record's daunting objective is also, however, an opportunity to reconsider and reimagine many of the things we take for granted, contemplating them as if for the first time. This is an idea integral to Broken Fence's fascinating debut A Light In Chorus - a first-person exploration game composed of luminous, undersea particles which casts you as an alien visiting Earth, playing back notes from the Golden Record to shift between a ruined, post-human future and the present day.

Billed as a "collage of light and sound", the game is the product of Johnson and studio co-founder Matthew Warshaw's on-going preoccupation with relics, edgelands and poisoned or precarious legacies, a fascination that began with the rapidly eroding coast of San Francisco. Johnson and Warshaw met while studying Fine Art at St Martins in London, and collaborated together in their spare time after graduating in 2009. "I'd been chipping away at a project for a few years - originally, it was about the Cliff House in San Francisco," Johnson tells me, against the reassuringly starless backdrop of a pub in Leeds. "Right now it's a restaurant, but it's this building that has been destroyed and rebuilt in parallel with the course of San Francisco.

"At one stage it was this Gothic, Victorian gingerbread house that was straddling the cliff, literally overhanging it. It's such a striking image, and in the 1940s they built a camera obscura next to it, which has this unique 360 degree mechanism." The latter contraption fills up an entire building, and features a revolving dome with a lens which projects a view of its surroundings down onto a viewing table. Johnson was fascinated by how the device inverted the role of a lighthouse, not casting its rays across the Pacific but siphoning the environment away, revolution by revolution, and collapsing it into an image. "I wanted to do a film about the history of that place, told using the camera obscura's 360 degree mechanism, as if it was like a black hole sucking stuff in, like the act of looking was destructive in a way."

The Cliff House film never quite took flight, but its salient ideas - of remoteness and precariousness mediated by curiously violent, deconstructive visual technology - found their way into a subsequent project for the London-based arts charity Artangel in 2013. "I submitted a proposal that refigured that project to be about this shipwreck, the SS Richard Montgomery, which is just off the Kent coast and still has loads of explosives on it. They have to do a survey every year to check on the stability of it, and it just so happened that the survey was done in Lidar, which has just the most amazing aesthetic quality to it."

A portmanteau of "light" and "radar", Lidar is a surveying technique that bounces laser beams from objects to create bewitching granular 3D landscapes; it has been used, amongst other things, to map out rainforest canopies from a passing plane, leaf by leaf. Johnson's film would have mysteriously transported the San Francisco camera obscura to the isle of Sheppey, and blurred footage of the mechanism with Lidar scans of the sunken warship. "It was going to be this film about how technology influenced the way we understand the world - technology's vision. And it got shortlisted, which was a real boost, but then it just sort of died, because I had to go back to work!"

Perhaps as a consequence of his growing interest in machine perception, Johnson's aspirations gradually shifted from film-making towards game development. The key inspirations were Twisted Tree's vivid procedural exploration game Proteus (which, I'm intrigued to discover, began life as something akin to an Elder Scrolls RPG), and Alexander Bruce's dizzying work of non-Euclidean geometry, Antichamber. "Something about those two games, it was: wow. I was going to art exhibitions and not feeling the same excitement as with Proteus especially - it blew my mind. It's such a consistent, contained work, every part of it just gels. And it was like, I could probably do this! Me and Matt go all the way back to uni, and we work in the right field. How hard could it be? Which is maybe a regrettable thing to think, four years in!"

With Warshaw taking care of much of the programming, Johnson created a couple of non-interactive, pre-rendered concept demos based on the Lidar footage, weaving terrain out of points of light. The game had no real narrative premise to begin with, but the use of dynamic, location-specific audio in Proteus eventually led Johnson and Warshaw to Bruce Chatwin's blend of anthropological narrative and existential thesis, The Songlines. In his book, Chatwin draws on study of the language and mythology of indigenous Australian tribes to suggest that landscapes are sung into being, mapped out and rendered navigable by particular tunes. "That seemed to immediately spark ideas about the potential of the Lidar points. Everything just overlapped. We thought what if we could tell this other story that was musical?"

Johnson and Warshaw were wary, however, of gleaning from Aboriginal tales directly for fear of misrepresenting them. They envisaged instead an imaginary continent based on the Outback, with players cast as animal spirits whose music gives rise to the very geography. The first of these entities, a shimmering stag, caused something of a stir among Harry Potter fans when Broken Fence shared it on social media. "I haven't seen all the films or read all the books, and all of a sudden we posted a gif of the deer and it got all these Patronus references, and we were like "What does this mean? Man, we've really got to ditch this deer."

The game foundered, however, as Johnson struggled to craft something arresting out of the austere Outback landscape. "There's not a whole lot you can do in environmental art terms - you're stuck with the wilderness. And part of the early appeal, when we didn't have a story, was just mashing up different ideas that worked really well for the style." In the end, the breakthrough for Johnson came from simply wandering through his own worlds, foraging for insights and parallels that weren't obvious at the time of creation. "It kind of happened through free association, walking around stuff that I'd made and trying to see it with new eyes each time, find the potential, and then eventually - there were lots of reedlike objects, and I thought 'these kind of look like seaweed'. And suddenly, everything I saw was the past." Johnson was already aware of the Golden Record, but it wasn't till he listened to a Radiolab podcast featuring Ann Druyan, the Golden Record project's creative director, that everything "clicked".

"It was musical and it was a disc, so as a visual motif, it was appropriate to all the Lidar points. There were issues of bandwidth, which was something I'd been interested in from the beginning - how much you can convey with so little information." The use of Lidar, he explains, is in part sleight of hand to disguise the crudeness of the base geometry, but as with the Record's constraints, this limitation has an oddly liberating effect. Players must, after all, join the dots to make sense of the landscape, which perhaps approximates the bewilderment of an alien archaeologist, struggling to reassemble the architecture and paraphernalia of a long-drowned society.

Alternating glimpses of urban Britain with water-logged edifices clotted with ocean fauna, A Light In Chorus speaks to the fatalism that lurks beneath the Golden Record's burnished surface. Working under the spectre of nuclear war with Soviet Russia, Druyan's team were keenly aware that they might, in fact, be constructing humanity's furthest-flung memorial. Hence the melancholy air of President Jimmy Carter's accompanying statement, "we are trying to survive our time so we may live into yours" - a line that rings as true today, in the thick of climate change, as in 1977. But like its inspiration, A Light In Chorus is inherently hopeful. Even as it posits disaster, it also shows how we might reacquaint ourselves with the topography of the everyday in more radical terms, as an alien terrain that needs tuning, rather than solid ground. By casting us as creatures from the beyond, ignorant of the preconceptions of human society, it implicitly invites us to question the institutions and systems that underwrite our world, and which are carrying it towards the abyss. In turning the Earth into a puzzle, it also suggests that this is a puzzle we can solve.