The man who made the NES

Meeting Masayuki Uemura, the engineer who helped take Nintendo into video games.

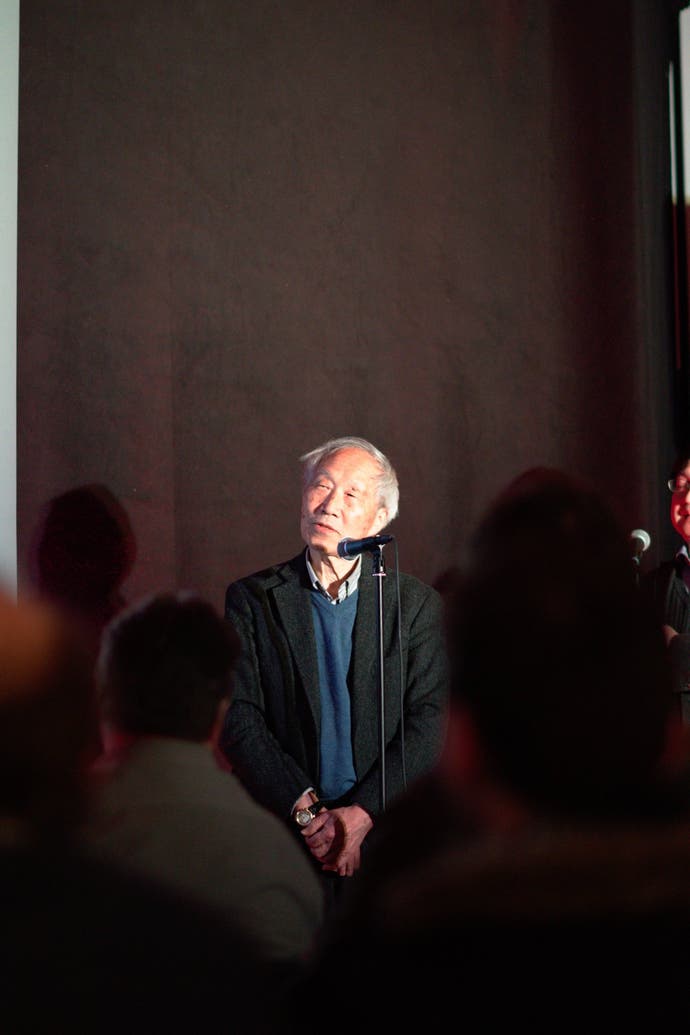

Maybe it's about being in the right place at the right time. How else to explain how Masayuki Uemura, an engineer born in wartime Japan to a humble background, came to change the course of video game history? Uemura is the man who designed the Famicom, a pivotal piece of plastic whose legacy can be seen throughout the modern industry; in many ways, it's the machine that defined modern Nintendo. "You know, it's only when someone like you comes along and asks a lot of questions that makes me think maybe I was a part of some big thing," he says with no small amount of modesty as we chat in a small, quiet space on the ground floor of Sheffield's Castle House.

The right place to be late last month was most definitely The National Videogame Museum, where the 76-year-old Uemura made the long journey from Kyoto to give a talk. The museum presents a thoughtfully curated collection with plenty of fascinating offshoots, from casual ephemera to a real, live Nintendo Dolphin devkit. And there are NES consoles, of course, the western version of the Famicom that took the world by storm throughout the 80s and established Nintendo as a giant of the entertainment industry.

The Nintendo that Uemura joined in the early 70s was still focussed on the trade it had been plying for the previous 80 years. "Back then they were only really manufacturing hanafuda cards," says Uemura. "That was it. They had top share for the hanafuda, but that was limited in terms of the size of the market, and it was decreasing constantly. That's why Nintendo decided to move into a new direction and into the toy industry."

Uemura was at the forefront of that shift; seconded from electronics giant Sharp, he shared the affinity many kids who grew up in wartime Japan had of making play things of whatever was to hand. "We had nothing, really," says of his childhood. "It was right after the war, so we just played with stuff like stones and bamboo sticks - but at primary school they started having rail train models and basic radios we created.

"At a primary school age, a fundamental memory I have was creating a radio out of these components - so I dreamed of becoming an engineer. When I joined Sharp, after graduating from college, I started selling solar cell batteries. Back then steel mills were using this technology - and that's how I started, selling these devices on. At Sharp I was able to sell this photo-cell technology to a lot of companies, including Nintendo. If I'd have moved to create semiconductors, it might have been a very different life..."

Nintendo and Sharp saw potential in the photo-cells for application in toys - specifically a light-gun game that Gunpei Yokoi went to work on. "The idea of making it a game was our proposal," says Uemura. "But the one thing that did surprise us was how fast Yokoi turned it into a prototype. To create a light-gun mechanism, the light has to be on pulse, so you can get the response quickly. If the pulse isn't being used correctly, then the sensor will detect luminescence from natural light, which will make it impossible for the light-guns to work properly. And it took only one week for him to do it. It was so quick - he was an amazing guy."

Nintendo's Kôsenjû SP series would prove to be a phenomenal success throughout the early 70s - enough to see over a million units sold, and for Uemura to be invited onboard full-time. "There was something different about Nintendo," Uemura recalled of the company he joined in David Sheff's Game Over. "Here were these very serious men thinking about the content of play. Other companies were importing ideas from America and adapting them to the Japanese market, only making them cheaper and smaller. But Nintendo was interested in original ideas."

"The success of the light-gun did change the strategy for us - after that we started focussing more on electrical toys," he tells me. "That's why they needed electrical engineering, and that's why they asked me to join. And when Nintendo decided to shift their strategy from hanafuda to electrical toys, there were no staff available apart from myself. I ended up coordinating personnel, as I was the only one who understood electrics and all the aspects around it, so I needed to find companies and partners to work with.

"The one thing I remember fondly is that those guys who had no experience with electrics were willing to learn and study and support me. From that perspective, it was a great company. And let's say I was at a regular electrical company - maybe I could design semiconductors, LSI, things with certain functions. To do the same thing at Nintendo - well, you could come up with a lot of ideas."

Uemura soon took up one of several key positions within Nintendo: Gunpei Yokoi headed up R&D1, where the Game & Watch would be birthed, Genyo Takeda headed up R&D3 while Uemura led R&D2 where his ideas would be put to use during another fundamental shift within the company. Having found some success distributing the Magnavox Odyssey, R&D2 partnered with Mitsubishi to create with the Color TV Game 6 - its first foray into dedicated gaming hardware - as well as a handful of successors. They were moderately successful, though the real game-changer was just beginning to take shape.

As sales of the Game & Watch slowed, Uemura was tasked by Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi with making a home console that could use game cartridges, giving it a longer shelf-life than the machines the company had been making in previous years. It was to be a machine made to Yamauchi's exacting standards - and to be bought in at under 5000 yen per unit. Working for Yamauchi - a famously stern leader - couldn't have been without its challenges, though Uemura has nothing but praise for his former boss.

"He was very respectful to the engineers," says Uemura. "He listened to our opinion really well. An engineer is someone who will prove whether or not we could do it - and of course, in many cases we failed. But Yamauchi would always give us an alternative - if it didn't work this way, then maybe try it this way."

Yamauchi's brashness and boldness helped Nintendo - then a minor player in the space - to success with the Famicom, as evidenced in some of his eye-opening strategies. When negotiating to partner with Ricoh for the manufacture of the console, Yamauchi persuaded them into business by gambling on a guaranteed order of three million chips - a gamble that must have placed quite some pressure on Uemura's shoulders. "I felt relieved," Uemura says with a light chuckle, "because it was a presidential decision and I wasn't involved in making it!"

It wasn't the last bold decision Yamauchi made regarding the Famicom - Nintendo famously recalled the first run of the console after a 1 percent failure rate was detected, at great cost to the company - but its success would go on to be legendary. Even then, Uemura still has some regrets regarding its design. "I didn't want to compromise on the graphics or sound capabilities," he says. "One thing I felt like I didn't succeed in was having controllers ingrained into the hardware - the cable was directly attached to the console, and it couldn't be detached.

"We tried, but from a technological perspective, and cost-wise, it didn't make sense. A connector was always expensive, and we had to ingrain the controller using a cable attached. And we thought we could only have one controller, on the first attempt, but we ended up with two. In a lot of cases, controllers ended up broken - and as you couldn't detach them so you had to send the whole system to Nintendo."

The Famicom still retained its quirks, too - such as the microphone included on the second controller, and sadly underused throughout the console's lifespan. It's a quirk that's always fascinated me, and I've always wondered what it was intended for - and whose idea was it? Uemura sheepishly raises his hand. "That was me..." he laughs. The intention was to capitalise on the karaoke boom in Japan at the time, though ultimately its most famous use was in Will Wright's Raid on Bungeling Bay in which players could call for help via that mic in the second controller.

Indeed, having two controllers feels included feels like another factor in shaping the Famicom's success, and in making it a device to be enjoyed by entire families rather than isolated players. "That was the president, Yamauchi," Uemura says. "The president needs to listen to us, and listen to the software designers - after that he could make a decision. The president tells the departments to cut cost, but also asks the software engineers what's the most ideal way to design the hardware - and they wanted this two-player mode as default. That's why he made sure to tell us the Famicom would support two players."

You can still see traces of the Famicom in Nintendo's modern consoles - indeed, one of the most striking was the Switch, a console first pitched around the idea of social play that, like the Famicom, shipped with two controllers attached to the main device. It's part, Uemura says, of the natural evolution process.

"When I developed the Famicom, I put all the basic functions that were necessary to make it as a gaming device," he says. "For the Switch, it's inherited all that over the years. All the successes and failures of the Famicom are inherited by the next generation of consoles and onward."

Uemura had left Nintendo by the time of the Switch - he officially retired in 2004 and took up teaching at Kyoto's Ritsumeikan University - but maintained an advisory role that meant he was party to seeing it take shape. "The idea for the Switch came around about five years ago," he says "The staff were asking for advice on what the next generation of Nintendo should be, and among them the idea of the Switch was already there. With Switch, the idea of a Game Boy-like device and a console-like device are integrated together. All the ideas of console games, and all the ideas of handheld devices, are pressed together. There's a lot of space in how you can play a game with that kind of console.

"It's an interesting cycle - handheld games came about with Game & Watch, aimed for personal use, then the Famicom came and we thought it was a game for people to play themselves by the TV but what happened was that families came together to play games, and socially-oriented games was the idea. Then the Game Boy came along for personal use - and then the Super Famicom, a mix of personal use and family or social use. It's an evolution process."

The Nintendo of today is, understandably, very different to the one that Uemura joined in the 1970s. Yokoi and Yamauchi are sadly with us no more, while Takeda retired in 2017. The old spirit remains, though. "There are still remnants of that culture there," says Uemura. "When you try and use a new technology, or apply it to entertainment, it has a lot of substantial influence on other industries and businesses. Nintendo's a really flexible company, they could change and evolve - when it's the right time, they'll change."

As for Uemura himself, I don't think I've ever met a more delightful interviewee. Happy, humble and with a rich history he's always willing to impart, he's the modest engineer who helped take Nintendo from card manufacturer to toymaker and well beyond. It's a life's work he has every right to be entirely satisfied with. "In my spirit, I'm always an engineer," he says as our brief meeting draws to an end. "But being an engineer only, it would not be possible - the passion for toys, that'll always be an important part of Nintendo."

Thanks to the National Videogame Museum for helping make this interview possible - and if you'd like a comprehensive history of how the NES was made check out Jeremy Parish's wonderful interview with Uemura on USGamer.