The Paradox of Fredrik Wester

What's behind one of gaming's most fascinating companies?

I missed out on Fredrik Wester the first time we crossed paths. At Paradox Interactive's 2013 conference, held in a somnambulist Iceland in the middle of winter, Wester did relatively little speaking. While the development teams present showed off a diverse roster of games like Cities in Motion 2, Leviathan: Warships and Impire, Paradox's commander-in-chief was content to let them advocate for their own work. He didn't speak for anyone, didn't seem to have any need to assert himself and, as I realise in retrospect, seemed to spend a great deal of his time just listening.

It was not what you might expect from the man at the helm of a company who, Forbes had just said, were enjoying 1000 per cent growth in gross revenue since 2006. That year was not a date chosen arbitrarily, but the year that Wester had founded the digital distribution platform Gamersgate and begun the tremendous shift that would see Paradox eventually earn 98-99 per cent of its sales online (Gamersgate is now an entirely independent company, but still carried the Paradox catalogue up until very recently). Both Magicka and Crusader Kings 2 had been huge recent successes and, despite the disastrous failures of concurrent games like Gettysburg and Sword of the Stars 2, the Swedish publisher had tremendous momentum. But, while so many of the decisions that had brought them that momentum came from Wester, it was often colleagues like Susana Meza Graham, Paradox's COO, or Shams Jorjani, the company's VP of acquisition, who did much of the talking. Wester was louder at the informal gatherings, singing or even playing air guitar, often the last person to talk business.

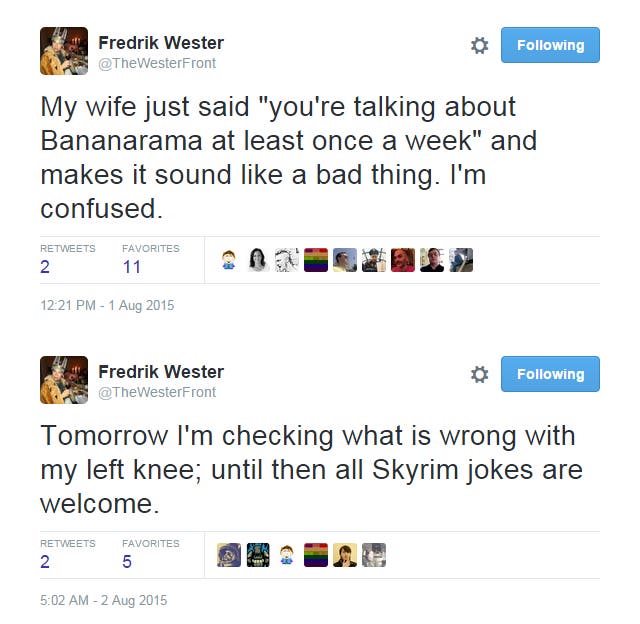

What I'd known of Wester at that point came mostly through other games journalists and from occasional very frank tweets that had become infamous. Wester spoke his mind, people said. Wasn't it refreshing that he sidestepped the PR machine to give a little dig at his rivals, or wasn't it amusing that he accidentally let a game announcement slip early? The impression one particular, smirking journalist gave was of an impulsive eccentric, slightly off-balance in his world, perhaps surprised at his own success and always on the verge of the next misstep. Yet this was not the Wester I would keep meeting.

"A normal day with Fred?" says Jorjani, chewing over the question. "He starts his day by putting on headphones and listening to opera. Very loudly. He sits down, he does a tonne of emails, but all his emails are very short. Then, he'll walk about the Paradox office, spot a meeting, say 'That's an interesting meeting, what's that about?' and jump right in. 'Hey! What are you guys talking about?'"

Jorjani is answering questions about his boss two years later, in the chilly, converted hotel-prison that Paradox has occupied for its 2015 conference. Again, the company is presenting a diverse portfolio to journalists, from the sequel to Magicka through to the grand strategy of Hearts of Iron 4 and the soon-to-be-megasuccess of Cities: Skylines. Once more, Wester has often been deferential, though he's spoken at length during the event's opening and also at a round table discussion where no topic was out of bounds. During that discussion, however, I couldn't help but notice him toying with his phone, checking the time, tapping at something or other. This was a man I could imagine bouncing from meeting to meeting, hungry for stimulation.

"We're trying to work on his attention span," Jorjani continues. "Fred is always working. He has so much going on. If anything slows down, the phone comes up. It can be very awkward in business meetings where we're getting something pitched to us. A developer's flown all the way out to Stockholm. Both of us realise, within two minutes, this isn't going to happen, but we've got half an hour and we have to sit through it. It's very challenging for Fred. Sometimes he just zones out."

What this is, Meza Graham explains to me over a Skype call, is a manifestation of Wester's drive, his desire to always be busy doing something. "He's always very full of energy," she says. "I feel like people get very motivated around him. He's great at rallying people and people are happy to follow him." Meza Graham has worked alongside Wester for a decade, during which she's seen Paradox grow from around 20 people to 180. It's not only been an enormous change in scale, but also in Wester's duties and the sort of things that demand his attention.

"He used to spend 250 days out of the year travelling, meeting developers, seeing if we could sign them for the publishing side of thing, or meeting sales partners," she says. "Back then, we didn't have the luxury to be talking to [the press] so much about what we were doing because we were too busy doing it." Since then, she tells me, Wester has stepped away from directly handling so many different tasks. "He has more perspective on things, but in terms of where he wants to take the company, the ambition, the drive, all of that is still there."

And even when I call Wester during an off-season holiday in Gran Canaria, he's still at work. "I spend the mornings playing football with the kids, but one, two, three o'clock I'm catching up with work," he explains. "Later, we'll go off and do something else, but I've always been like that. The only time I really have off is during Christmas, because nobody is working during Christmas."

We talk at length about his history with the company, his previous work and his family's entrepreneurial background, but one of the first things he's quite happy to tell me is that, yes, he can certainly lack focus and he's not always good with details. "I lack a lot in following up," is how he puts it, pointing out how much the company has grown under him.

"I've come to realise that working very closely with me can be challenging for people," he says. "I'll say, maybe, '[These are steps] A, B, C...' but then people have to figure out the rest of that alphabet. I know exactly where we're going to go with the company, but I also know that a lot of this only stays in my head and only comes out in fractions when I talk to people. I need to sit down with myself, remind myself that I'm now communicating with 180 employees. When you're just ten, you can talk to people every day, everyone will know everything. There's no challenge in communicating. The last two years, I've had a lot of work to do figuring out how I keep all our people on board, rowing in the same direction. I'd say my job is now a totally different thing to how it was even three years ago."

I have to admit, I can't quite get a sense of this man yet. Meza Graham tells me she believes Wester is brilliant: "He's great at identifying potential and talent in people." Jorjani is adamant that he has an ability to spot something good. They also acknowledge that he can be restless, unfocused and, Meza Graham says, "Sometimes he does my head in. 'Can you just decide on one thing?'" How has this man overseen a company that has grown eight times as large, that has pioneered digital distribution, that has gone from having a catalogue of games widely considered to be hugely variable in their quality to enjoying over $18m in revenue in the weeks after the launch of its two biggest titles, Cities: Skylines and (shared with Obsidian) Pillars of Eternity, all while remaining independently owned?

It doesn't hurt to start early.

"I've been running companies, big and small, since I was 16," says Wester. "I have an entrepreneurial background, both myself and through family as well. On my dad's side, basically everybody is running a company in one form or another. If you took a Christmas at my dad's place, he has three brothers and they're all entrepreneurs. Everything they talked about at Christmas was business. And Premier League football. With my grandfather. Who was also an entrepreneur." There may well have been some influence there, Wester concedes, as he describes to me that first teenage foray into making money, in all its ambition and naivety.

"Me and my brother were huge Nintendo players. We started importing Nintendo games from Taiwan," he says. "Games which we later figured out were pirate copies, but back then we didn't have a clue, we just thought 'Wow, these are really cheap Nintendo games!' They were also all in Japanese, so we had to translate all the manuals." Wester doesn't say how good the translations were, but he may have missed one or two key details that would have hinted these weren't authentic products.

"Running a business as a high school kid is very challenging. Often you have no idea what you're doing," he says. "Pirated games? We had no idea. I had no idea how to fill in the paperwork. I had no idea how to do the taxes. You have to figure out everything, do everything from scratch. You get these tax forms sent to your home and go 'Shit, how do I do this?' And there was no internet, no way to Google how to do these things. But somehow, we got it to run." For the short term, at least. Eventually, Nintendo caught up with the Wester brothers.

"My mum got a cease and desist letter from Nintendo in Sweden, telling us to stop selling these games. Still, I guess that was my first games company, of sorts. So, really, my background is actually in pirated games..."

The story of how Paradox Interactive came to be is one I've touched on before, but some specifics reveal a great deal more about Wester's business vision. Working as a consultant in what he calls CRM ("Customer relationship management, the thing everyone was talking about in the late 90s and early 2000s. I implemented customer service tools and products to revolutionise how people did customer service over the internet."), Wester was hired by a company called Paradox Entertainment to assess their computer games division. After investing months of time and energy in a thorough business plan he had a surprising meeting with the company's board of directors.

"They said 'We're not interested in developing this company any more. We don't think there's a future for this company in computer games and we're going to shut down that division,'" he recalls. "That was a bit of a shock." Inspired by what he had seen after an initial skepticism toward video games, Wester joined forces with Paradox Entertainment's former CEO, Theodore Bergquist, and took control of the jettisoned division. It was an opportunity too good to miss.

"When I joined Paradox it was not with the intention to take over," he continues. "I really didn't enjoy being a consultant, but when I had the chance to bring some order to this little group of developers, I thought it was a great challenge. I can make a change here. If we hadn't been there to take over, the company might just have been shut down and remembered as another one of those grand old developers. We thought there was a future for these games and if we could just sell them to an audience who was dedicated, they had a great chance of succeeding."

Wester went ahead with one of the core ideas in his business plan: not only developing video games, but acquiring others as a publisher. He was excited about a lot of the games Paradox made and keen to find more, something that Meza Graham says was "very unusual" at the time. "You were either extremely into games or you were very much a business CEO. You didn't have the two back then. It might be more common now, but I think that's been one of the key factors in Paradox's success."

Meza Graham was one of Wester's early hires during a period where he describes as very disorganised. "My first job was just to get everything in order," he says "When I joined just simple things like the file structure on the main server was a mess. Everything was in chaos, but I figured, if I could just get the business to run, I already had this bunch of dedicated and brilliant developers."

Both Jorjani and Wester say the earlier days of Paradox Interactive were "fast and loose," with mistakes made, corners cut and even money saved in one or two novel ways. Wester seems particularly proud of one "pro tip for small developers" from the company's 2005-2006 period.

"When we went to E3 I stayed at the cheapest motel possible, really cheap," he says. "But I had all my meetings booked at the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills. Now, that's probably one of the most expensive hotels in L.A. or in America. So when people came in to meet me, I was sat there, in the lobby with my laptop, and they were all saying 'Wow! This is a nice hotel!' And I would say 'Yeah! Isn't it?!'"

The second time I met Wester, at a preview event in Stockholm, he was as deferential as the first, though there was certainly no flashy hotel backdrop. Underdressed and attentive, Wester did none of the corporate promotion I'd expect of a CEO, was not "on brand" and had no desire to hog the spotlight. He turned up to a café in a tracksuit, learned everyone's names, shook hands and then mostly soaked in the discussion. I was still expecting a CEO who might want to take charge of the situation, to guide the conversation, but Wester instead took the time to learn each journalist's name and see what they were interested in. Then, the moment there was a lull, he left to catch up on more work.

Every meeting or Paradox convention since has been similar. Following the pattern Jorjani describes, Wester drops in on something, listens, may contribute to the discussion or ask pointed questions, then is already on his way to the next event. Jorjani says his boss likes to make decisions quickly, but also informed.

"You don't come to a meeting with Fred unprepared. You use your time well and you make sure you come away with a direction," says Jorjani. "Two minutes into [a developer's pitch] he can be saying 'Okay, let's do this! What are the business terms?! When can we sign?! Can you come over and finish the contract next week?!' That's an attitude we all try and maintain at Paradox, in business, with media, with sales partners. There shouldn't be a whole lot of red tape. You should be able to get an answer quickly, to get results quickly. That comes from Fred. He has a very low tolerance for inefficiency."

His directness has lead Wester in all sorts of directions and not every decision made quickly has been a good one, with the early days of Paradox's portfolio a testament to this. Alongside many of the grand strategy games that were the company's backbone for so many years, there's many forgettable and even derided titles. But Wester and his colleagues were working quickly and intently, engaging as directly with their customers and potential clients as they could. In 2005, he had already approached George R. R. Martin to discuss the possibility a company that was excited about fantasy and strategy making a Game of Thrones tie-in. Meanwhile, he was urging his colleagues to be direct and open not only with each other, but also with their customers or, as Paradox wants to call them, fans.

"A lot of the people I saw in bigger organisations were hiding behind their brand," says Wester, recalling his time as a consultant. "I was telling everyone 'Stop hiding behind your brand and actually talk to people, talk to customers, answer their questions. People have concerns about how you conduct your business and their connection with you. All you have to do is communicate.' The more you do it, the more you'll be rewarded by your community."

It's this frankness and honesty that often defines so many perceptions of Wester and Paradox. If Wester believes a Paradox title was bad, he'll happily acknowledge this, but at the same time he has also been a passionate advocate for games he's excited about, big or small. "There might be a couple of reasons you don't like Pillars of Eternity," he tweeted, in advance of the game's release. "The most obvious one would be that you don't like good games." It was a classic Wester statement and it's not difficult to see why, from the outside, Wester's defining characteristics might be frankness and perhaps even belligerence. Yet, again, this doesn't fit with the patient listener who, Jorjani says, "talks to everyone in the company. He might seem an intimidating figure because he's the CEO, but he has this very disarming way of approaching you."

He's also a man who, by his own admission, has found the continued growth of his company difficult to deal with. His colleagues say he likes to speak with everyone and that he appreciates people who will disagree, who will give alternate or even dissenting opinions. But as Paradox and its portfolio have expanded, it's become impossible for him to maintain the same level of involvement. The intimacy and level of enjoyment he once enjoyed is lost. Indeed, if Wester is frank about anything, he's certainly frank about this.

"Previously, I'd mix everything together and I could work with three, four different things in a day," he says. "Now, there are longer projects that take more of my attention and, if these projects don't speak to my strengths... I'll do it, because I'm the CEO and it happens to be my task, but I'm kind of an emotional guy and people can see if I'm happy or not with what I'm doing. I can try to put on a poker face, but I know I'm a very bad poker player as well, so I've started to tell people 'You know what? Right now, I'm not feeling at my best and I hope you respect that.' Instead of trying to hide what I'm feeling, I'm deciding to be even more open about it. It's helped me a great deal to be a better CEO."

"Our growth has been very difficult in the sense you can't grow without relinquishing some power," says Jorjani. "It went from Fred being in charge of everything to our having a management team. Everyone on that management team is in charge of their department and they do it very well, so the question now becomes: What is Fred in charge of? It's difficult for him, I think, but it's also difficult because he realises it's necessary. He doesn't want to be the CEO who micromanages everything. At the same time, that's what makes it frustrating. When everything was smaller, he used to have more direct insight."

The impact of Paradox's growth upon Fredrik Wester is a subject both Jorjani and Meza Graham touch on several times and have a very acute awareness of. While the company has changed around him, Meza Graham "still recognises the Fred of ten years ago. He's stepped away and has more perspective on things." He has, she says, always known how he wants to develop the company to exploit new opportunities and investments, but knows he can no longer manage, or even completely understand, every facet or element of Paradox. "He's really worked on trying to become a better manager and on working closer with the [new] management team," she explains. "He's invested time in himself not as a leader, but as a manager."

Wester says all this means he's now even more focused on management and business tasks and less on contributing to ideas in game development games. "Maybe that's one reason our games are better today," he laughs, as he thinks about the change. "I have less time to pitch in on them!" That's surely a comment born of gentle self-deprecation, I respond, having seen him happy to laugh at himself or his faults to make others feel at ease, but he stays the course: "I don't know. It might also be true!"

Well-known amongst Paradox fans is the story of how Wester chipped in to write the manual for the Crusader Kings game, a title in which he saw tremendous potential. In 2004, a still brand new Paradox Interactive was cutting those corners with its motel tricks and, also, by skimping on writers.

"We needed to cut down on the budget for the manual," Wester remembers. "So I said 'You know what? I can write this!' It was two hours after I said it that I began to regret it. I'd never written a manual before in my entire life and I hated it. If you're a guy like me, who hates administration, trying to explain to people how to do things in a certain order? I suck at that and you can see that in every personality test I do. When we released the game, people were asking 'Who on earth wrote the manual? It's straight up terrible.' But I was still really proud of it. It's one of the best jobs I've ever done, because the hell it had me go through, yet I still did it."

Unfortunately, that first Crusader Kings didn't enjoy the success its sequel did, becoming another early Paradox title that failed to fulfil its promise. Wester attributes this to financial constraints at the time. "We didn't have the money to execute it, to make it what it could have been, so everything was bootstrapped. I put together an e-commerce site in three weeks, together with a Swedish company, and a promise to pay for everything months later. We packed and shipped all the boxes ourselves because it was too expensive to hire people. Two hours after work every day."

What the experience did reflect, however, was Wester's vision for how a game like that could succeed and how willing he was to invest in that, to put himself behind it. The second time Paradox took a shot at Crusader Kings, they made that vision a reality, surprising even themselves with just how well Crusader Kings 2 was received. Yet Wester had always felt that idea would bear fruit. He gets behind games, one former colleague tells me, because he really does believe in them, not because he's a PR simply employed to promote them. He can, Jorjani says, sometimes spend "long, long" periods of time playing a Paradox title, before surfacing with strong opinions about it.

If Wester's very different experience as a CEO atop a much-enlarged company is one thing Jorjani and Meza Graham are aware of, the other is his vision. They have no hesitation in ascribing so much of Paradox's success to Wester's ability to anticipate what may become popular, to be cannily aware of change in the video game industry and to see the potential in either a video game or even a future employee. Both acknowledge his restlessness, need for the new and lack of sustained focus (something Meza Graham balances with aplomb "When I discuss things with Susana I can scrap maybe nine ideas out of ten straight off," is how Wester puts it), but both also offer appraisals that, at times, border on the gushing.

"I remember Susana saying, during my interviews [to join Paradox], that one of the biggest reasons she stayed at Paradox was Fred," says Jorjani, "Because she learned something new from him almost every day. It's been the same for me. He's a huge part of why I'm with the company. If he ever left, I have a hard time imagining staying. It's very hard to imagine a Paradox without Fred and if he were to quit and do something else, I'd be willing to follow him just to see what the next thing is."

That doesn't seem likely any time soon. Restless as he may be, Wester is still excited about what Paradox does and proud of its growth. Now, the company can afford to broaden its portfolio further and, after previously having to release almost everything to recoup its investments, it's increasingly ruthless about dropping titles it believes aren't up to scratch, titles that are never even announced.

It's a sound business tactic to spread investments this way, and Jorjani describes it as like playing poker, where blind luck can win one or two hands, but sensible and skilful play will pay out in the long term, in spite of ups and downs. "Paradox has had growth and stability for a long time in a very turbulent industry," he says. "That's thanks to the fact that Fred almost never plays the short game. It's always the long game. Everything we do is driven by his vision of building things long term." Certainly, Paradox is enjoying more successes more often, while avoiding more outright disasters. The long game is working. Increasingly, the visions are being realised.

"The ups and downs in my work have been [more significant] in the last three or four years than ever before," says Wester to me, over that slightly fuzzy line to Gran Canaria. There's some sort of sound in the background that makes me think someone is chopping vegetables.

"Sometimes now I have to do things that take months and which are not things I see myself doing or that speak to my strengths at a CEO," he continues. "I'm not going to be the best CEO possible during that time, because I'm going to feel like these aren't the things that are going to make me shine. But then I'll get to work with our business models, work with our products, sit down with Shams [Jorjani] and discuss our portfolio, and that's where the highs come back. Then I know where we stand, that we have everyone on board. Then I can focus on the fun stuff."

There aren't many businesspeople I've seen speak so plainly about their ups and downs in the games industry. Certainly many creative figures will, acknowledging the difficulties they've faced while trying to make their art, but Wester isn't a game designer, developer or creative lead. He's a businessman and part of what are supposed to be the suits upstairs, a group often portrayed as the bad guys in the industry, opaque in their decision-making, unknowable and uncaring executives disconnected from the realities of their trade and so very particular about what they say on the record.

But that's not Fredrik Wester. Nor is Fredrik Wester a collection of glib tweets, nor an impulsive man propelled forward only by his enthusiasm, nor a man who got lucky with the right investment at the right moment. He's frank in telling me that, though he hopes the day might never come, Paradox Interactive may grow so large or so different that he can't find his place in it any more. If that happened, he would have to let his creation go.

At this year's Paradox convention, in that chilly converted prison, Wester says he'd still make the mistakes he has over again, that Paradox would still pick up unsuccessful titles like Gettysburg or Impire because they were the right games for the time, because "From a conceptual standpoint, these games are still the sort of games we want." And those games have also taught them lessons. The process of growth and development that Paradox has gone through has taught both Wester and his company a great deal. "Mistakes should be made once," he adds in an email. I'm not sleepless over mistakes made in the past, I make sure we learn from them." He still believes that, on the whole, he's good at choosing both games and people.

I ask the man in Gran Canaria if, looking back, he'd hire himself, a person who admits they can be imperfect, restless, distracted. He sounds amused, having told me that Paradox hire based as much on attitude and outlook as they do skill-set. He ponders for just a moment, but his answer is quick and decisive.

"I think I would," he replies. "I'd say 'This is a guy who has a lot of attitude and a lot of skill... but he has no clue how to focus all that energy.'" Even as he answers, it sounds like he's stepped into yet another room. The acoustics have changed. There's movement. There are people nearby. He's definitely doing other things as well as talking to me, isn't he?

"Yes," he acknowledges, quite honestly. Somewhere, a door opens, and a line he has just said to me perfectly explains everything about Wester's attitude and actions.

"I like it when things happen."