The universal appeal of Chicory: A Colorful Tale and its nuanced take on mental health

"The picture that you have of somebody is never accurate."

"Could I learn to be a better me? I guess I'll have to try." So sings a magical paintbrush-wielding dog atop a mountain in a colouring book world as they come to terms with what it means to be a hero.

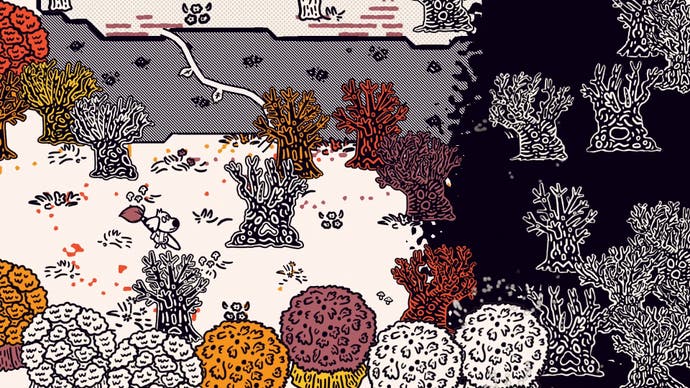

Chicory: A Colorful Tale is a cute cartoon game on the surface about a (literal) underdog on a heroic quest. But beneath that, the game explores darker, adult themes that touch on perfectionism, imposter syndrome and issues of mental health.

That song, a duet between the player character and the titular Chicory, strikes at the heart of the game, its folky melody and simple lyrics belying a serious message.

"I think for almost no reason I was like 'there should be a musical number at some point'," says game developer Greg Lobanov. Luckily, composer Lena Raine had already begun writing a suitable melody, so the song came together almost by accident.

"I'm really really glad we did it," says Lobanov. "I was surprised at how much it captured just a lot of different things that I'd been thinking through. I'm really glad that we got it in."

Lobanov has become known for developing games that focus on player creativity. His previous game Wandersong allows for improvisation with its singing mechanic that's used to solve puzzles. Similarly, in Chicory, the player colours the world with a paintbrush to interact, creating their own artwork in the process.

And while Chicory has been celebrated for its touching story, gameplay was its foundation.

"The starting point was I wanted to make a game where the player did art and drawing as the main way of interacting with the world," says Lobanov. "I was interested in making an adventure game and playing some kind of story, but the early phase was just design concept stuff, trying different ways of drawing on the screen and figuring out how to make it fun with a controller and what the camera perspective is going to be. Just trying to make a fun drawing adventure."

So what is it about player creativity in gaming that's so fascinating?

"It's really fun to make stuff," he says. "I'm really passionate about it. I make games because I love it a lot. I don't know that I set up a life goal to make games about this stuff.

"It's weird more games aren't exploring stuff like that, because every human being has drawn in their life and had fun doing it. It seems obvious to me it would be a really fun basis for a video game."

To an extent it has been done before with the Capcom-published Okami, a game about a wolf with a magical paintbrush. But Lobanov says that game wasn’t an inspiration - actually it was the opposite.

"Okami's actually a really good example of a thing I really didn't want to do, which is where you're playing an adventure game, like a platformer, and then you go into drawing mode," says Lobanov.

"Ocarina of Time has music in it, but you go into music mode to play music and then you leave music mode and you actually play the real game where you're fighting zombies or something. I wanted to do a game where the drawing mode is the game."

The game recently won the BAFTA Games award for Family game and Lobanov and the team certainly had children in mind, despite some of Chicory's more complex themes.

"I always thought about how a little kid would feel playing it," says Lobanov. "It was tough to manage. But I think it's also a really fun constraint, the way the story unfolds and the kind of themes that it explores. We put effort into trying to make it all in language that was plain and understandable."

He cites the likes of Steven Universe and Over the Garden Wall as key inspirations. "All my big inspirations target young audiences, but deal with lots of stuff and I love that vibe. That was my goal."

A balance of light and dark was required in the art and the storytelling to ensure universal appeal for children and adults alike.

"I think you can make an emotional story with just about any art style," says game artist Alexis Dean-Jones. "For the characters in Chicory, it was really important to me they were big enough to be able to have clear emotions and facial expressions and body expressions, because that's how I'm used to storytelling from animation."

Lobanov adds: "Basically focusing on appeal and relatability, making characters that feel genuine - that was the grounding for us."

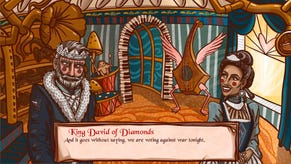

The titular Chicory, who suffers a depressive episode, was a tricky character to get right. In early builds of the game, some playtesters thought she was a villain.

"We wanted her to be a character that people would like," says Lobanov. "But it's actually really hard. It was basically hard to find that line where you understand that she's going through something difficult, but that you still want to help her."

Dean-Jones adds: "We don't want to excuse her behaviour, but we do want you to empathise with her and see that she’s struggling and trying to do better."

The game isn't biographical and wasn't intended to be specifically about mental health, but those themes grew from the team's personal experiences.

"[Mental health] felt like an inevitable thing we had to talk about, if we were going to make a game about art, because of all the feelings we have about art, doing art, and being in that community, and all the complicated feelings that we have," says Dean-Jones.

"As we started leaning the story that way and trying to figure out how we were going to do that and all the complicated things that was going to introduce, it made working on the game very meaningful for me, a lot more personal."

Her experiences with OCD also drew parallels with the character Chicory, Dean-Jones says.

"I realised that I needed to talk to people about it," she explains. "And once I actually started talking to my friends about it, I found out they were going through stuff as well. And that just unlocked a different level of our friendship because you could be comfortable talking about those things if one of us was having a particularly rough day or something. I think it's very healthy to talk about it in that kind of environment."

Issues like this are handled with nuance in Chicory, adding depth to a heroic adventure game that has more to say than simply saving a princess. Yet the pair want adults and children to each take something different away from the game - or, young and old artists.

The player character is "a kind of person who doesn’t think of themselves as an artist... this person who's coming to this world that they're not familiar with and learning how to express themselves and be comfortable with that," says Lobanov. Chicory, by contrast, is "speaking to a different kind of person who’s really been through it and is not really liking art anymore".

But what does the game mean for Lobanov and Dean-Jones?

"I relate probably most to the [player] character," says Lobanov. "Being somebody who struggles with inadequacy and is surrounded by people who are more talented. And also trying to learn how to be a good friend to somebody who's having a hard time. Those are all things that were important to me with the game."

"What felt really important to me were the relationships between all the characters and I wanted to make sure they felt authentic," says Dean-Jones.

"About [the player character's] journey particularly, learning their self worth and learning to value their own self expression and not judging or measuring yourself against the picture that you have of somebody because the picture that you have of somebody is never accurate."

Chicory teaches the player that through creativity we can all learn to be better. We just have to try.