With gaming's internet usage climbing, how do internet providers keep up?

On Call of Duty, cables and connections.

When Modern Warfare 3 released last year, it pulled in some serious numbers for internet service providers (ISPs). The game's launch and pre-load period resulted in record traffic across EE and BT, which the companies reported as the "biggest single game contribution to a broadband peak". But what does this really mean? And how do ISPs cope when gaming traffic spikes occur? I spoke with EE's director for gaming and future propositional development Sam Kemp to find out.

Inside EE's network - as with any ISP - are records of games and other media in a cache, or CDN. "CDN is a content distribution node inside our network," Kemp says. "Whether it's the latest Apple software release, the latest Fortnite download or the latest Call of Duty game, we work with all of our partners globally to bring all of that content into our network... so when you call down on that film, that game, those maps, it's already in our network." This enables ISPs like EE to provide these downloads as fast and as directly as possible, with metrics "we know are really important to gamers", Kemp says, like "jitter, packet loss, latency, packet sequencing".

He compares EE's work adjusting internet signals - specifically when gaming on a smartphone - to a musician tweaking the "fine-tuned dials at the end of a violin or guitar. If you turn them all in the right way, you get the best sound".

"We can put thousands of pieces of content and games into these caching nodes and [any] of the eight million broadband customers we have can all call down individually on a particular game. There is no complex prioritisation that needs to be done based on a per customer per location part of the UK," he explains, and no rivalry between content types if a big Netflix show launches the same day as Call of Duty. There is "no prioritisation given across the network".

If a game isn't cached, your download request "routes out across the internet in the way that you would with a Google search," Kemp explains. "It doesn't mean it's a poor experience, it means it's probably going to be a very comparable server, because there's going to be much less demand going out on that route to, I dunno, retro Pac-Man games."

This works whether you're on a device connected wirelessly to a 4G or 5G mast, or at home, with fixed broadband - although with a fixed line there are other considerations. "Everything that happens in the home goes down a cable to the same core network the mobile network is connected to. It's a much simpler path," Kemp tells me. But congestion can occur within the home itself. "Whether you've got somebody downstairs streaming a Netflix video, somebody in another bedroom downloading a cooking recipe, and somebody in the next room trying to have a semi-competitive game of Call of Duty, the congestion comes because it's your own Wi-Fi, your own router."

With a better understanding of how the network works, I ask what service providers actually see when we use the internet. Can they simply take a look on their end, and say 'Aha, we have an influx of mobile gamers right now'? Well, yes they can. "Not only can we see the types of traffic demand on the network, we actually plan ahead," Kemp elaborates. "[EE has] a 10-year strategic partnership with Microsoft, and we talk to all the other software makers, games houses globally. When we see those spikes coming in the network, the network is optimised for it [and] we have the capacity to scale to meet those spikes."

ISPs are having to respond rapidly as gaming demand continues to grow, Kemp says, though they have been aided by the growing rollout of 5G and superfast fibre to more postcodes nationwide. These allow providers to increase network capacity and prevent congestion during peak times, on top of having content - such as the launch of a new Call of Duty - cached within networks to ensure "the right capacity, the right scalability" is primed and ready.

"We see them, prepare for them and optimise the network at the same time," Kemp says of big gaming events. "We saw on Call of Duty about a 113 percent increase in the spike of data [compared to normal internet demand]. Compare that to a live Premier League football match, which is normally about a 30 percent spike in traffic," he continues, noting that gaming traffic peaks can be up to a "six fold" above. But not every gaming spike can be predicted.

"Some things we can't predict, right, because it's just a naturally occurring event," Kemp says, noting that particular gaming competitions can provide unexpected peaks. "But whether it's a download or an upgrade, or a new Fortnite set of maps, by and large for the majority, we get those with good warning."

How about the likes of Helldivers 2, a game few predicted would hit the player counts that it has? "We've never been caught out from a scalability perspective, because we build the networks to scale well above what they can ever actually generate in live consumption," Kemp says. That said, even live consumption can spark surprises - such as the release of last December's big GTA 6 reveal trailer. That, Kemp admits, was "fascinating" to watch.

"[We saw] 80, 90, 100 million views spike up a lot quicker than you would expect for any other trailer or demo of a game that's been released in the market," he says. The trailer quickly broke YouTube records and became the most viewed video in 24 hours (that wasn't a music video), hitting an astonishing 90m in its first day. "The network is always primed and ready, but we definitely see spikes we hadn't planned or expected. And when these kinds of trailers are released, you see this massive demand on the network at one particular time."

I picture a team of little men and women like Oompa Loompas rushing to pull and stretch the internet cables wider to get more data through. "Well, I can't call our network field team Oompa Loompas! But I've now got visions of Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory and trying to find synergies of that and how we run a network," Kemp laughs.

Running a network means having a hard-working crew behind the scenes. Kemp pays tribute to the "guys and girls that go around in vehicles, servicing the masts, making sure that computing power works, the antennas are pointing in the right direction and they're powered and cooled sufficiently... Think about what they have to deal with on a weekly basis - winds, storms, rain, water ingress, floods," Kemp says. "Then, on the fixed side, you've probably seen the Openreach-type teams going around. They are also servicing the network, making sure it is optimised and always there."

The work of both teams then feeds back into the ISP's data centres, where work is done to optimise for "the bigger aspects of content delivery, optimisation, availability" and where teams can plan for those game downloads, or "a particular TV show that is expected to go particularly well".

I ask if ISPs like EE perform any fancy calculations ahead of a launch, based on game size and player base? Does the download file size or estimated player numbers make a big difference? "It's more along the lines of the recognition [of a game]," Kemp replies. "With Call of Duty, we know that game will drive significant demand in both download upgrades so we know we'd need that game in our content delivery network. The maths part is just how many people are on our network," Kemp explains.

"We take great pride in making sure we get these games and updates into the network as quickly as possible, giving us enough time before the game is released so we can optimise the network for people to draw down on it.

"Rather than it being about a mathematical equation, it's more about what's happening in the industry. What games do we think are going to be the biggest and making sure we have those. And through those relationships with studios and games houses, we try to get the majority of all of the AAA titles into our content delivery network, because we know gaming traffic is increasing year-on-year, and the gaming industry is not tailing off in terms of demand."

As well as needing a technical handle on how the internet works, simply having a knowledge of video games matters more and more, Kemp says. In the company are staff with "a plethora of knowledge across mobile gaming, PC, console, you name it... and it allows us to build a sort of gaming roadmap for the year ahead." Kemp adds that gaming network traffic has been growing steadily "15 percent year-on-year", and is currently "about a £7-8bn market in the UK alone".

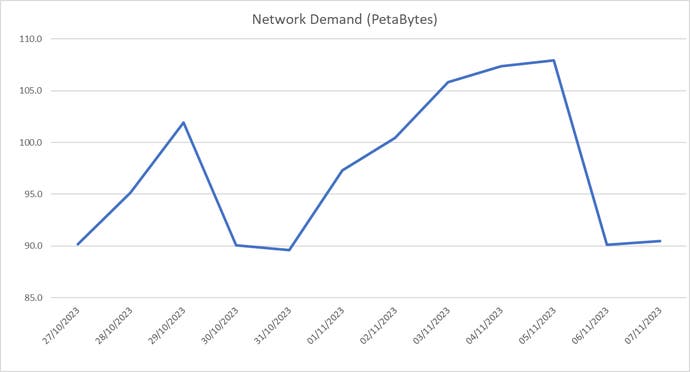

Gaming now makes up almost 10 percent of all broadband traffic on EE, although that figure can increase to nearer 20 percent when new games launch. "Two petabytes of data are being used every month for mobile gaming alone," Kemp says, noting that this part of the market is seeing a real boom. (For context, 2PB is the equivalent of watching an HD film non-stop for 3.5 years). "That is almost double what we saw at the start of 2023. It's massive, massive."

Games such as Call of Duty will typically spike "within the first 72 hours" of the game's download becoming available, before things "feather off into standard traffic consumption" over time. But Kemp notes that live-service games like Fortnite "hold a much higher monthly play rate, so the spikes will look as big as a Call of Duty, but the average time in gameplay will be far greater."

Where does gaming go next, as more of us play online for longer? "Network evolution will start to track gaming evolution," Kemp tells me. "We are spending a huge amount of time, certainly in research and development looking at 'what do our network equipment suppliers have on their roadmap? What does the gaming industry have on its roadmap? And how can we join the dots?'.

"We're going to move into a world with 5G slicing or 5G mobile edge computing or when we get close to two gigabits per second of home fibre broadband. We will see eSports and competitive gaming evolving. We should expect games like Call of Duty to make massive advancements in their production facilities that need the demands of the networks.

"For me, building networks that are fit for the future is our number one and two priority in gaming at the moment," he says. "We will be having, hopefully, this conversation in two years time and we'll be in a spatial computing environment, where we'll be watching your gameplay over the weekend. And networks will have to serve that capability in a different way than it has to serve it today."

I tell Kemp I have moved on from picturing Roald Dahl's Oompa Loompas to imagining myself conducting an interview as a Star Wars-like hologram. "Totally! I mean, as a massive Star Wars fan and a technologist, we are destined to get to that point in the very near future," Kemp laughs. "There is no doubt networks will have to continually evolve and transform to serve those future-based services to make sure that we can actually deliver on that Star Wars promise."